Some years you chase new releases. Others, you return home.

2025 was a year for old friends. Fifteen films spanning six decades, each one landing differently than before. Some I covered in articles. Others whispered quiet reminders of why they mattered in the first place. And one—The Grey Fox—kept its annual appointment with me because some traditions are sacred.

I'm not going to draw this out. I tend to do that sometimes. These are quick-fire recommendations for you to enjoy over the festive break. Fair warning: some spoilers ahead.

This isn't criticism. It's memory.

The 1960s: Fellini's Creative Crisis

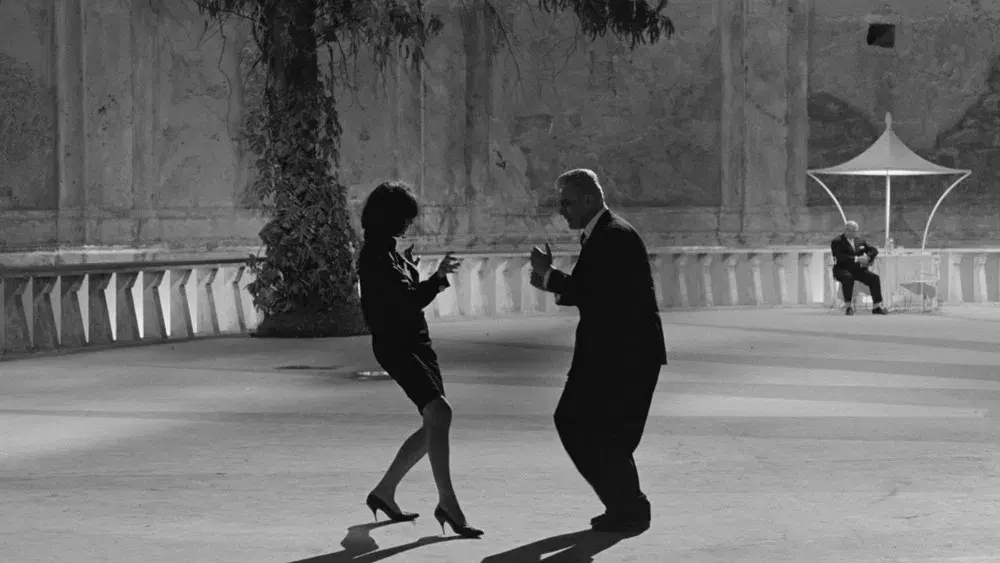

8 1/2 (1963) still feels like watching someone's mind unravel in real time. Fellini's meditation on creative paralysis shouldn't be this playful, this seductive. Marcello Mastroianni drifts through memories and fantasies, unable to make his next film, lying to everyone including himself.

The circus music. The spa sequence where past and present collide. That ending—choosing chaos over silence. I forgot how much joy lives inside the existential dread. Nino Rota's score alone justifies the revisit. This is the film about filmmaking that filmmakers still can't escape.

The 1970s: American Darkness and Light

New Hollywood's Beautiful Violence

Terrence Malick's Badlands (1973) plays like a fever dream. Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek drift through murder with such detachment you forget to breathe. Sissy's voiceover—that flat, childlike narration—makes the horror float. "He needed me now more than ever, but something had come between us." The something is bodies.

Wide Dakota skies. Empty roads. America as blank canvas for doomed kids. Ninety-five minutes that never drag.

The Passenger (1975) gave me Antonioni's slowest burn. Jack Nicholson steals a dead man's identity and discovers the past won't let go. That seven-minute tracking shot at the end—unbroken, hypnotic—remains one of cinema's greatest magic tricks. Patience rewarded in full.

Portraits of Survival

Ellen Burstyn in Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974) is Scorsese at his most human. A widow, a kid, a dream of singing that might be delusion. She picks the wrong men. Makes the hard calls. The Oscar was earned. Those diner scenes still crackle.

Charles Burnett's Killer of Sheep (1978) is poetry disguised as documentary. Shot on weekends in Watts. Stan works a slaughterhouse. Exhaustion defines everything. But watch the couple slow-dancing in their living room. Kids jumping rooftops. Etta James and Paul Robeson on the soundtrack adding weight to small moments. Visual jazz. American neorealism at its purest.

Further Reading: Check out Our Picks of 70s Classics

Underdogs and Bicycles

I covered The Bad News Bears (1976) this year and it still surprises me. Walter Matthau coaching little league misfits sounds safe. It isn't. The kids swear. The adults are deeply broken. Tatum O'Neal pitches strikes and takes zero prisoners.

They lose the final game. But they find dignity. Sometimes that's the bigger win.

Read Next

From the Vault

Breaking Away (1979) got its own article too. That post-graduation limbo when you're trapped between what you were and what you'll never be. Working-class Indiana kids in a college town that excludes them. Dennis Christopher escaping into Italian cycling fantasies. Cutters versus students. Class warfare in bicycle shorts.

Peter Yates directs with such warmth, but the ending knows small victories don't fix structural inequality. Bittersweet doesn't begin to cover it.

Pure Genre Joy

The Incredible Melting Man (1977) is trash elevated by Rick Baker's grotesque makeup effects. An astronaut returns from space dissolving into goo. Bodies melt. A nurse gets decapitated, her head floating in a bloody stream. None of it makes sense. All of it entertains.

B-movie comfort food. Sometimes you just need practical effects mastery and zero pretension.

The 1980s: Thieves, Outlaws, and Class Warfare

Mann's Neon-Lit Perfection

Michael Mann's Thief (1981) set the template for everything that followed. James Caan cracks safes with surgical precision. Wants one last score. The plot is nothing. The execution is everything.

That opening heist—wordless, just Tangerine Dream synth and Caan's hands working—established Mann's visual religion. Neon streets. Professional codes. Men who can't escape their own competence. The diner scene with Tuesday Weld is one of cinema's great first dates. Vulnerability and violence sharing the same booth.

When Frank dismantles his life in the final act, it's cathartic and devastating. Control slipping through fingers that crack safes but can't hold love.

The Annual Pilgrimage

I watch The Grey Fox (1982) every year. This is not negotiable.

Richard Farnsworth's Bill Miner—gentleman outlaw released after thirty years—finds the Old West gone. So he robs trains. Politely.

"I'm sorry, I'll have to trouble you for the express box."

Farnsworth brings such dignity. A lifetime stuntman making his dramatic breakthrough in his early sixties, embodying obsolescence and grace. The romance with Jackie Burroughs feels earned. Two lonely people, late in life, finding each other without melodrama.

Philip Borsos shot British Columbia like a painting. The landscapes ache. I return every year because this film reminds me that choosing your own terms matters more than winning. Grace over glory. Always.

Decade's End—Horror and Heart

Brian Yuzna's Society (1989) is body horror as class rage. Beverly Hills kid discovers his wealthy family literally feeds on the poor. The final twenty minutes—Screaming Mad George's practical effects nightmare—is flesh as protest. Bodies merging, reshaping. The rich consume the working class. The metaphor lands because Yuzna commits fully.

Reagan-Thatcher era subtext. Not subtle. Doesn't need to be.

Rob Reiner's When Harry Met Sally (1989) hit different this year. We lost Reiner last week. Watching it again felt like saying goodbye to someone who understood that love is mostly two people talking, arguing, and choosing each other anyway.

Nora Ephron's script dances around one question: can men and women be friends? The answer unfolds across twelve years. Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan have chemistry you can't fake. The restaurant scene is iconic, sure. But Harry's scrambled eggs demonstration matters more. Sally's specific ordering rituals. Those interview segments with real couples grounding the fantasy.

Jazz score keeping everything light while hearts break and mend. This is why romantic comedies worked before they forgot how.

The 1990s: Addiction, Vampires, and Redemption

DiCaprio's Descent

The Basketball Diaries (1995) refuses to flinch. Leonardo DiCaprio's Jim Carroll falls from high school basketball star to heroin wreckage. Based on Carroll's autobiographical novel. No glamour. No moralising. Just the spiral.

That scene where Jim begs his mother for money through the locked door—desperate, lying, breaking—is brutal. You feel both sides.

Mid-90s New York grit. Basketball courts and shooting galleries. Friendship corroded by need.

DiCaprio proving his range years before anyone fully noticed.

The Vampire Film That Changed Everything

I spent considerable time on Blade (1998) this year. Full article. Interview with Stephen Norrington. The revisit confirmed what I suspected: this film birthed the modern superhero era and never got proper credit.

Before Marvel's universe. Before Nolan's Batman. Blade proved comic book properties could be dark, stylish, financially successful. No camp. No apologies.

Wesley Snipes owns it. That opening nightclub sequence—blood raining from sprinklers—announced a new aesthetic. Stephen Dorff chewing scenery. Martial arts meeting gunplay with kinetic fury.

The world-building holds. Gothic atmosphere, practical effects, vampire politics that feel functional. The CGI blood aged poorly. Everything else endures.

Blade arrived too early and too cool to be taken seriously. History corrects slowly.

Lynch's Gentlest Gift

David Lynch made The Straight Story (1999) without surrealism or nightmares. Just the American Midwest and Richard Farnsworth—yes, him again—driving a riding lawnmower 240 miles to reconcile with his dying brother.

Farnsworth was 79 and terminally ill during filming. Gone the following year. Every scene carries that weight. An actor embodying mortality with quiet dignity. The Oscar nomination felt like the world finally noticing what we already knew.

The ending: Alvin and his brother Lyle (Harry Dean Stanton) sitting wordlessly under stars. No grand speeches. Just two old men finding peace.

Lynch, master of darkness, delivered his most humane work. A fitting end to the century.

What Connects Them

These fifteen films share outsider blood. Characters operating at margins, confronting systems that exclude them. Small victories mattering more than grand triumphs. Filmmakers trusting audiences to keep up without hand-holding.

Malick, Antonioni, Burnett, Lynch—they all embrace patience. Cinema communicating through image and silence as much as dialogue.

They reward revisiting. First viewings reveal story. Subsequent viewings expose craft. You notice the editing choices, the musical cues, the performances deepening with familiarity.

That's why The Grey Fox keeps its annual appointment. Why 8 1/2 still surprises. Why Blade demands reappraisal. Great films don't diminish. They expand.

2025 gave me space to rediscover old friends. Some neglected for years. Others—like The Grey Fox—never truly left. Each viewing confirmed that authentic cinema transcends fashion.

See you in 2026.

Keep on Rewinding!