John G. Avildsen had cracked the code twice. Rocky in 1976 earned him the Oscar for Best Director and became one of the most culturally significant films of the decade. The Karate Kid in 1984 saved his career after years of commercial disasters and launched another phenomenon. Both films followed identical DNA: underdog protagonist, older mentor figure, unconventional training sequences, climactic fight, emotional triumph over adversity. Same director, same composer (Bill Conti), same narrative blueprint, same crowd-pleasing formula.

It worked spectacularly. Twice.

So when Avildsen returned in 1992 with The Power of One—following that exact same structure—it should have been another cultural landmark. Every element was there: the underdog (British boy navigating apartheid South Africa), dual mentors (Armin Mueller-Stahl as Doc, Morgan Freeman as Geel Piet), training montages, boxing matches, a climactic showdown with his childhood nemesis. Even the mantra echoed Mr Miyagi: "First with the head, then with the heart."

The formula was intact. The craftsmanship was there. Hans Zimmer composed the score before his massive success. The cinematography was stunning. Daniel Craig made his film debut. Stephen Dorff delivered an authentic accent and performance.

What happened?

Opening weekend: $684,358.

Total worldwide gross: $2,827,107.

Production budget: $18,000,000.

The film didn't even cover its marketing costs, let alone recoup production. An 84% loss. A catastrophic bomb.

American critics destroyed it. Peter Travers called it "a violent cartoon that trivialises apartheid." Entertainment Weekly said it "becomes their victimiser" by depicting "South Africa's blacks as an anonymous horde of victims." Roger Ebert wrote: "The Power of One begins with a canvas that involves all of the modern South African dilemma, and ends as a boxing movie. Somewhere in between, it loses its way."

The consensus was brutal: white saviour narrative. Tone-deaf. Patronising. A Hollywood formula clumsily applied to historical trauma.

Here's what makes this story fascinating: the critics weren't entirely wrong about what they saw—but they completely misunderstood what they were watching.

The Formula That Conquered the World

Rocky and The Karate Kid aren't just commercially successful films. They're cultural DNA. Training montages became universal cinematic language because of these two films. Bill Conti's scores defined inspirational music for a generation. The underdog narrative became the blueprint for sports films, coming-of-age dramas, and feel-good cinema for decades.

Both films made underdogs relatable through identical beats:

Rocky Balboa: Small-time Philadelphia boxer, working-class Italian immigrant background, given an impossible shot at the world champion. Mickey, the gruff gym owner, becomes his mentor. The meat-locker training, the iconic museum steps, the final fight where he doesn't need to win—just prove he belongs.

Daniel LaRusso: Working-class kid from New Jersey, moves to California, gets bullied by rich karate students, finds Mr Miyagi. The "wax on, wax off" training disguised as chores, the crane kick, the All Valley tournament where he defeats his tormentor despite injury.

Same director. Same composer. Same emotional architecture. The formula was so successful that Columbia Pictures literally asked writer Robert Mark Kamen to create "Rocky for kids" when developing The Karate Kid. Avildsen even jokingly called it "the Ka-Rocky Kid" during filming.

When he applied this blueprint to The Power of One, adapting Bryce Courtenay's semi-autobiographical novel, the pieces aligned perfectly:

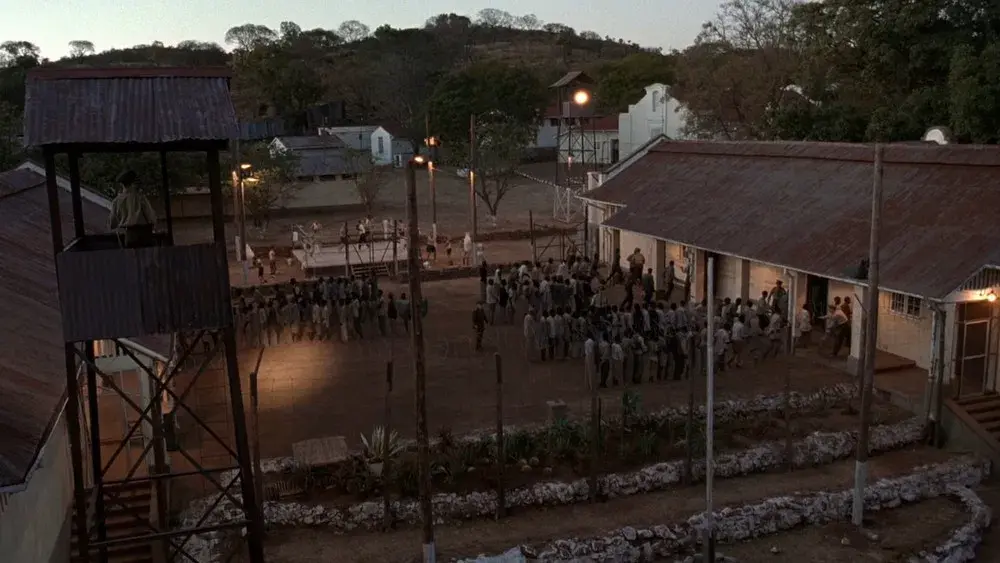

The Underdog: PK (Peter Philip Kenneth), English boy born to a widowed mother, sent to Afrikaans boarding school, bullied mercilessly, finds identity through boxing.

The Dual Mentors: Doc (Mueller-Stahl), a German pianist whose family was executed by Nazis, teaches him music and resilience. Geel Piet (Freeman), a Cape Coloured boxer, teaches him to fight with the mantra: "First with the head, then with the heart."

The Training: Boxing sequences intercut with South African landscapes, PK learning discipline and strategy.

The Antagonist: Jaapie Botha (Daniel Craig in his debut), PK's childhood bully grown into an apartheid police sergeant, the swastika-tattooed neo-Nazi who terrorised him at school now wielding state power.

The Climax: PK defeats Botha in a street fight, symbolic victory over both personal trauma and systemic oppression.

Beat for beat. The formula that made two cultural icons.

So why did it bomb so catastrophically?

The Power Of One Gallery: TMDB

What American Critics Saw—And Why They Saw It

In March 1992, The Power of One opened in limited release. To understand why critics responded the way they did, you need to understand the moment.

| Event | Date | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| The Power of One releases | March 27, 1992 | Opens to $684,358 opening weekend |

| South African apartheid referendum | March 17, 1992 | White South Africans vote to end apartheid—10 days before US release |

| Rodney King verdict | April 29, 1992 | Officers acquitted; LA riots erupt. Race becomes the only topic in American media |

The film walked into a perfect storm.

America was about to explode over the Rodney King verdict. Every film depicting race relations was being scrutinised through this lens. A feel-good apartheid boxing movie starring a white protagonist, released one month before the LA riots, with inspirational training montages set to Hans Zimmer's percussive, choral score?

Roger Ebert captured the fundamental tension: "The Power of One wants to be more than the story of a young man whose life reflects the times of his country. It also wants to be a box office hit, and in playing the notes of mass entertainment, it loses its purpose."

He wasn't wrong about the formula being visible. His critique revealed something deeper: "The little neo-Nazis are led by a punk with a swastika tattooed on his arm, and at the point where that same tattooed arm turns up attached to a bullying officer of the state security force, I knew the movie was lost."

Translation: this felt too neat. Too Hollywood. Too much like a boxing movie grafted onto serious historical trauma.

Entertainment Weekly went further: "The Power of One spends so much screen time revelling in the eloquence and bravery of its hero and depicting South Africa's blacks as an anonymous horde of victims that the film, in effect, becomes their victimiser."

From a 1992 American perspective, this looked like textbook white saviour narrative:

- Privileged white protagonist positioned as hero

- Black South Africans as background figures

- Morgan Freeman (one of the most recognisable actors in the world) playing a mentor who gets beaten to death by police

- A white boy opening a school to teach English to black students

- Boxing matches framed as symbolic of liberation struggle

The formula that worked brilliantly for Italian-American boxers in Philadelphia and bullied teenagers in California felt exploitative when applied to apartheid.

And here's the thing: critics weren't entirely wrong to question this.

Centring a white protagonist in an apartheid story is a legitimate creative choice to scrutinise. The tonal dissonance of inspirational training sequences—even with Hans Zimmer's percussive, choral score deeply rooted in African musical tradition—immediately following scenes of black prisoners being brutalised was jarring. In the world of 1992 prestige cinema, that tonal whiplash felt like bringing a pop-rock anthem to a funeral, regardless of the actual instrumentation. When the music hits the same emotional beats as classic sports drama during sequences depicting life under apartheid, it creates friction.

These are fair critiques. The question isn't whether critics were right to be uncomfortable.

The question is: were they uncomfortable because of poor filmmaking, or because they lacked the cultural framework to understand what they were watching?

The Hidden History: The British/Afrikaner Divide

Here's what American critics didn't know, couldn't know, and never bothered to find out:

PK wasn't "white South African" in any simple sense. He was British.

That distinction matters profoundly.

South African history isn't just white versus black. It's British versus Afrikaner versus black African populations, with violent antagonisms between all three groups stretching back centuries.

The Boer Wars (1880-1881 and 1899-1902) saw British forces fighting Afrikaner settlers—descendants of Dutch, German, and French Huguenot colonists who saw the British as imperial oppressors. The British won but left deep scars. They'd burned Afrikaner farms, imprisoned families in concentration camps (where 26,000 Afrikaner women and children died), tried to destroy their culture and language.

By World War II, many Afrikaners sympathised with Nazi Germany. Not metaphorically—literally.

The Ossewabrandwag, a pro-Nazi Afrikaner organisation with an estimated 300,000 members at its peak, committed acts of sabotage against the British war effort. They saw Hitler's Germany as a model: ethnic nationalism, resistance to British imperialism, Afrikaner supremacy as state policy. Future Prime Minister John Vorster was interned during the war for his Ossewabrandwag activities. BJ Vorster would go on to architect some of apartheid's most oppressive legislation.

The Power of One depicts this explicitly. The opening boarding school sequences show Afrikaner boys conducting mock Nazi tribunals, worshipping Hitler, tattooing swastikas on their arms. These aren't dramatic exaggerations. This happened. When PK arrives with his British heritage, speaking English rather than Afrikaans, he becomes a target.

His mother is English. His culture is British. In 1930s-40s South Africa, that made him an enemy to Afrikaner nationalism.

The film shows PK's nanny, a Zulu woman, raising him alongside her own son. She comforts PK while her own child lies in a crib next to her—a devastating image of her capacity for love under profoundly unjust circumstances. PK identifies with her, with Tonderai (her son), with the black prisoners he encounters through Doc. Not because he's choosing to "help" them from a position of power, but because he recognises shared outsider status.

When Afrikaner boys beat him for being British, kill his pet chicken in ritual humiliation, force him into Nazi-style ceremonies—PK isn't experiencing mild bullying. He's experiencing ethnic persecution from children who will grow up to enforce apartheid as state policy.

Daniel Craig's Sergeant Jaapie Botha is the same boy who tattooed a swastika on his arm at boarding school. Now he wields apartheid police power. The through-line isn't Hollywood convenience—it's historical reality. The children who worshipped Hitler in the 1930s became the architects and enforcers of apartheid in the 1948 National Party government.

American critics saw this and thought: contrived. Too neat. Reducing complex history to one villain.

They had no idea this was documentary accuracy.

The Paradox Nobody Could Hold

Here's where it gets genuinely sophisticated.

PK exists in a paradox that 1992 American racial discourse couldn't process:

Simultaneously:

- Genuinely victimised by Afrikaners (bullied, beaten, persecuted for British heritage)

- Genuinely connected to black South Africans through shared outsider status

- AND structurally privileged over them purely by skin colour

He could:

- Attend prestigious Prince of Wales School in Johannesburg

- Date Maria Marais (an Afrikaner girl) even if secretly

- Open a school for blacks using his access and immunity

- Move freely without pass laws

- Have his boxing success celebrated publicly

- Be surveilled for subversion rather than immediately arrested and beaten

His black counterparts—Gideon Duma, Tonderai—couldn't do any of that regardless of talent, character, or achievement.

The film actually shows this tension explicitly. There's a scene where police are beating a black man. PK wants to intervene. You can see him calculating: if I step in, I become a sympathiser, I become a target. But he has a choice. That's the privilege. A black South African couldn't hesitate—they'd already be on the ground getting beaten, or arrested for daring to question police authority.

PK benefits from the system even while opposing it. He can be a "symbol" for black resistance precisely because he has the platform and protection they're denied.

American critics wanted binary: oppressed OR privileged.

The film offered: oppressed within white society AND privileged within racial hierarchy.

That's not white saviour narrative—that's the moral complexity of being a white anti-apartheid activist. You can't shed your structural advantages. You can choose to forfeit safety and belonging, but you can't share the full burden of oppression your black allies carry.

The film doesn't shy away from this. It shows it. But understanding it required cultural literacy American critics didn't possess.

The Stories That Prove It Was Real

Here's the defence The Power of One never got to make properly: this wasn't Hollywood invention. This was documented, lived experience.

Bryce Courtenay, who wrote the novel, drew heavily from his own childhood. Born in South Africa in 1933, English-speaking in an Afrikaans-dominated environment, he experienced exactly this marginalisation. The book is semi-autobiographical—PK's story mirrors Courtenay's own.

But there's an even more striking parallel: Johnny Clegg.

Born in England in 1953, moved to South Africa as a child, Clegg began learning Zulu music and culture from black street musicians as a teenager. He formed Juluka in 1969—the first genuinely multi-racial band in South African history, at the height of apartheid.

His trajectory mirrors PK's:

- White, British heritage

- Learned from black mentors (Zulu musicians teaching him traditional songs and dance)

- Genuine connection to black culture through authentic relationships

- Used white privilege as platform (international tours, press coverage, some protection from race)

- Became targeted by the apartheid state (concerts raided, music censored, under surveillance)

- Called "The White Zulu" by press

And here's the kicker: The Power of One uses Johnny Clegg's music in the soundtrack. Avildsen was deliberately invoking this real-world parallel.

Multiple white South Africans with British heritage lived versions of this story. Courtenay. Clegg. Helen Suzman. Alan Paton. Donald Woods. That's not an anomaly—that's a pattern. A documented cultural phenomenon.

American critics in 1992 didn't know any of this. They saw "white boy boxing in Africa," projected American racial dynamics onto it, and stopped there.

The Power Of One (1992) Gallery: TMDB

Why the Critics Were Right to Be Uncomfortable (But Wrong About Why)

Let's be honest about something: the tonal whiplash in The Power of One is real.

Hans Zimmer's score—percussive, choral, deeply rooted in African musical tradition—still hits the "inspirational" emotional beats of classic sports drama during PK's training sequences. The boxing matches deliver crowd-pleasing catharsis. The film wants you to cheer, to feel inspired, to leave uplifted. And it does this while depicting a system that brutalised millions, killed thousands, destroyed families, enforced white supremacy through state violence.

That's jarring. Critics weren't wrong to feel that tension.

Rocky worked because the worst thing that happens is Apollo Creed trash-talking Rocky and a brutal boxing match. The Karate Kid worked because the worst thing that happens is teenage bullying and a karate tournament. The formula was designed for stories where "triumph" doesn't require ignoring massive ongoing suffering.

The Power of One tried to apply that same crowd-pleasing template to a story set against one of the 20th century's most oppressive regimes. Training montages with inspirational music—however culturally authentic the instrumentation—immediately after scenes of black prisoners being beaten. Romantic subplots while pass laws separated families. A feel-good ending while apartheid still had decades to run.

Critics felt that dissonance and assumed it was exploitation. Assumed Hollywood had grafted a formula onto trauma for profit.

What they missed: PK's story genuinely fits that narrative shape because people like him genuinely existed. The formula wasn't distorting reality—it was reflecting a specific reality. But the tonal choices still created legitimate friction.

The film asks you to feel good about an individual victory within a system that continued to crush millions. That's a hard sell. Maybe an impossible sell.

The question becomes: should Avildsen have made a grittier, more sombre film? Should he have abandoned the formula that was his signature? Should stories about white anti-apartheid activists avoid inspiring music and crowd-pleasing moments entirely?

Or is there space for a film that says: yes, systemic oppression is horrific, AND individuals found moments of connection, dignity, and triumph within that system, AND those moments mattered to them, AND we can depict that without trivialising the larger horror?

American critics in March 1992, one month before the LA riots, weren't interested in that nuance.

Read Next

From the Vault

The Weight of 1992

The 1980s had already delivered a wave of "Africa films":

- Out of Africa (1985): White colonists' romance

- The Color Purple (1985): Black American story, but set in Africa for key scenes

- Cry Freedom (1987): Steve Biko's story told through white journalist

- Gorillas in the Mist (1988): Dian Fossey, white conservationist

- A Dry White Season (1989): White teacher awakens to apartheid

By 1992, American audiences were exhausted with prestige films set in Africa, especially ones focused on white characters navigating racial injustice. The formula felt done. The Oscar bait was obvious. Cynicism was high.

Then The Power of One arrived with:

- Another white protagonist in Africa

- Another "awakening to injustice" narrative

- Training montages with inspirational music

- A crowd-pleasing boxing climax

Plus the timing:

- Released March 27, 1992

- South African referendum ending apartheid: March 17, 1992 (10 days prior)

- Rodney King verdict: April 29, 1992 (one month later)

- LA riots: April 29 - May 4, 1992

The film opened during peak American racial tension, in a moment when any story centring white characters in a racial justice context was being scrutinised with zero tolerance for missteps.

It never stood a chance.

Critics saw the Rocky formula applied to apartheid and reacted with revulsion. They didn't have the time, the cultural knowledge, or the inclination to understand what they were actually watching.

The Power of One required homework. It required understanding British/Afrikaner history, Ossewabrandwag, the specific position of English-speaking white South Africans, the documented existence of cross-racial mentorship under apartheid.

1992 America wasn't interested in homework. Not about this. Not then.

What It Felt Like to Live It

I was born in South Africa in 1981. British heritage, just like PK. Just like Bryce Courtenay. Just like countless others who lived this exact paradox.

My parents weren't racists—the opposite, in fact. I was practically raised by Beauty, our domestic worker. That was her name: Beauty. I never questioned why she lived with us, cooked our meals, cleaned our home. I was too young to understand the system that made her presence in our house possible and necessary.

I never saw her as anything other than family.

She taught me the Zulu way. My parents taught me the western way. I hold onto her teachings to this day. The respect, the patience, the capacity for love she showed despite everything our society did to her people—I didn't understand the weight of that until much later.

Only as an adult did I realise: she gave up time with her own family to be part of mine. That still hurts to think about today. Her impact on my life cannot be described.

That scene in The Power of One where the nanny comforts PK while her own child lies in a crib beside her? That's not Hollywood sentiment. That's not manipulation. That's millions of South African childhoods. Domestic workers raising white children, loving them genuinely, while being separated from their own families by pass laws and forced relocations.

The film isn't patronising to those of us who lived it. It's recognition.

Walk into any room of South Africans who lived through apartheid and mention The Power of One. Watch what happens.

They'll tell you about their Beauty, or Anna, or Joseph. About learning Zulu or Xhosa from people whose names they remember decades later. About the complexity of being white and privileged while also being genuinely connected to black South Africans who taught them, shaped them, became family.

They'll tell you the film captured something true: that many white South Africans—particularly those with British heritage—did actively oppose apartheid. That genuine friendships formed across racial lines despite the system. That the capacity for black South Africans to show love and patience to white children whose society brutalised them was real and profound and devastating.

The scene where PK hesitates to intervene when police beat a black man? That's not clumsily showing white privilege. That's capturing the exact moral calculus white anti-apartheid activists faced: how much risk are you willing to take? What are you willing to forfeit? What can you actually change?

Yes, PK had choices black South Africans didn't have. Yes, that's privilege. The film shows that. It doesn't excuse it or ignore it. It depicts the moral complexity of living within that paradox.

American critics saw white saviour narrative.

We saw our own complicated, painful, contradictory history.

The Verdict

John G. Avildsen didn't fail with The Power of One. The formula didn't fail. The craftsmanship didn't fail.

Cultural translation failed.

The film required audiences to understand:

- British/Afrikaner antagonism dating back to the Boer Wars

- Afrikaner Nazi sympathies during WW2 and their direct line to apartheid architects

- The specific, documented existence of white British South Africans who opposed apartheid

- The paradox of simultaneous marginalisation (within white society) and privilege (within racial hierarchy)

- The authentic phenomenon of cross-racial mentorship that defied the system

American critics in March 1992, watching through the lens of American racial dynamics, one month before the LA riots, fatigued by "Africa films," couldn't decode any of that.

Could Avildsen have made different choices? Absolutely. A grittier film with less inspirational music. A more sombre tone. More screen time for black characters. Less focus on PK's personal triumph.

But that would have been a different film. It wouldn't have been Avildsen's film. And it's worth asking: would American critics have praised that version, or would they have found different reasons to dismiss it?

Cry Freedom took the serious, sombre approach—focused heavily on Steve Biko's story, made the white protagonist guilt-ridden and secondary—and still got criticised for centring the white journalist.

The film has a 7.1/10 on IMDb from over 8,000 user ratings. That's higher than several Karate Kid sequels. The audience that found it—mostly people with South African connections—recognised its authenticity. It just never got the chance to find a broader audience because critics killed it on arrival.

Sometimes the greatest sin isn't making a bad film. It's making a film that requires its audience to think harder than they're willing to. That demands cultural homework. That refuses to fit neatly into the moral frameworks audiences bring with them.

The Power of One demanded that. March 1992 America wasn't interested.

The film found its audience eventually—scattered, international, mostly people who recognised the specific history it was depicting. But it never got the cultural phenomenon status it might have deserved with different timing, different marketing, or critics willing to interrogate their own assumptions.

Avildsen's formula didn't fail. The audience failed the film.

And maybe that's the real story about cultural stories that don't travel: sometimes the failure isn't craft. Sometimes it's not even timing.

Sometimes it's the gap between what a film is trying to say and what an audience is equipped to hear.

The Power of One is available on various streaming platforms and physical media. For those interested in the broader context, Bryce Courtenay's original novel provides additional depth to PK's story, while Johnny Clegg's music (particularly his work with Juluka and Savuka) offers a sonic companion to understanding white South African anti-apartheid activism through cultural connection.