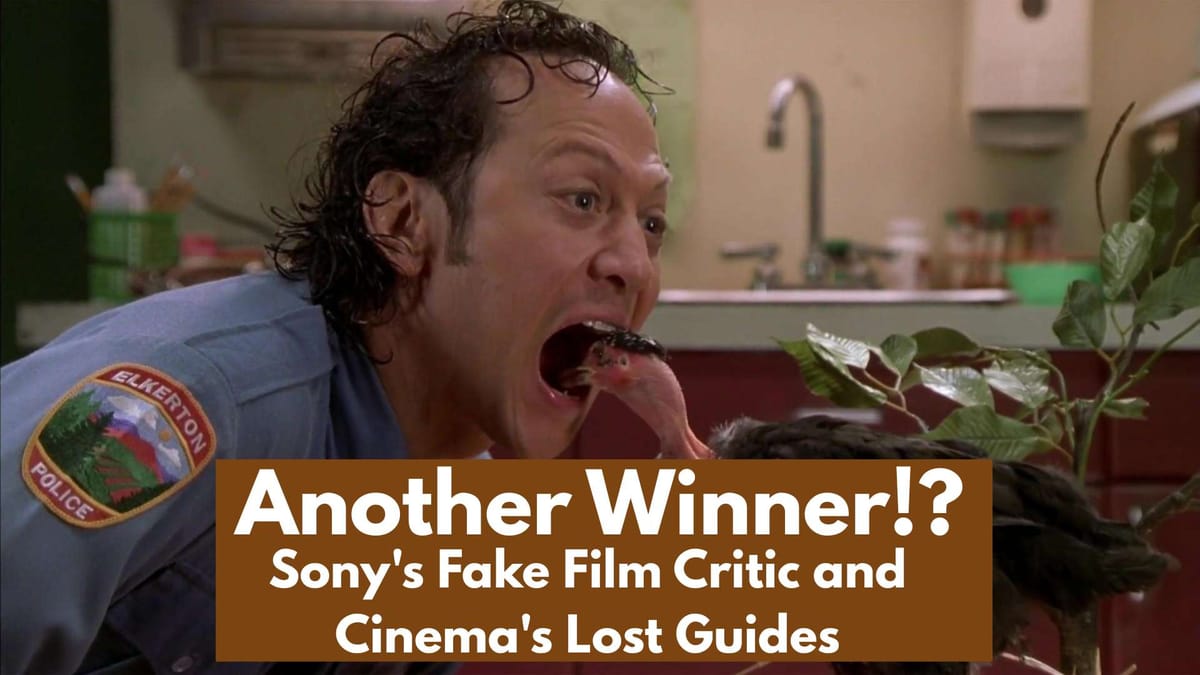

There's something deliciously ironic about a fictional film critic praising terrible movies.

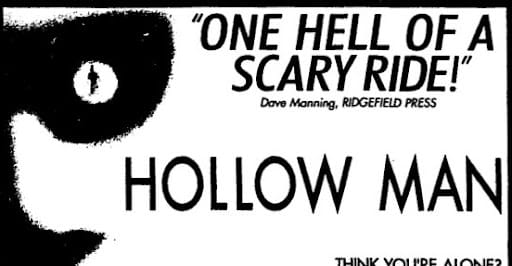

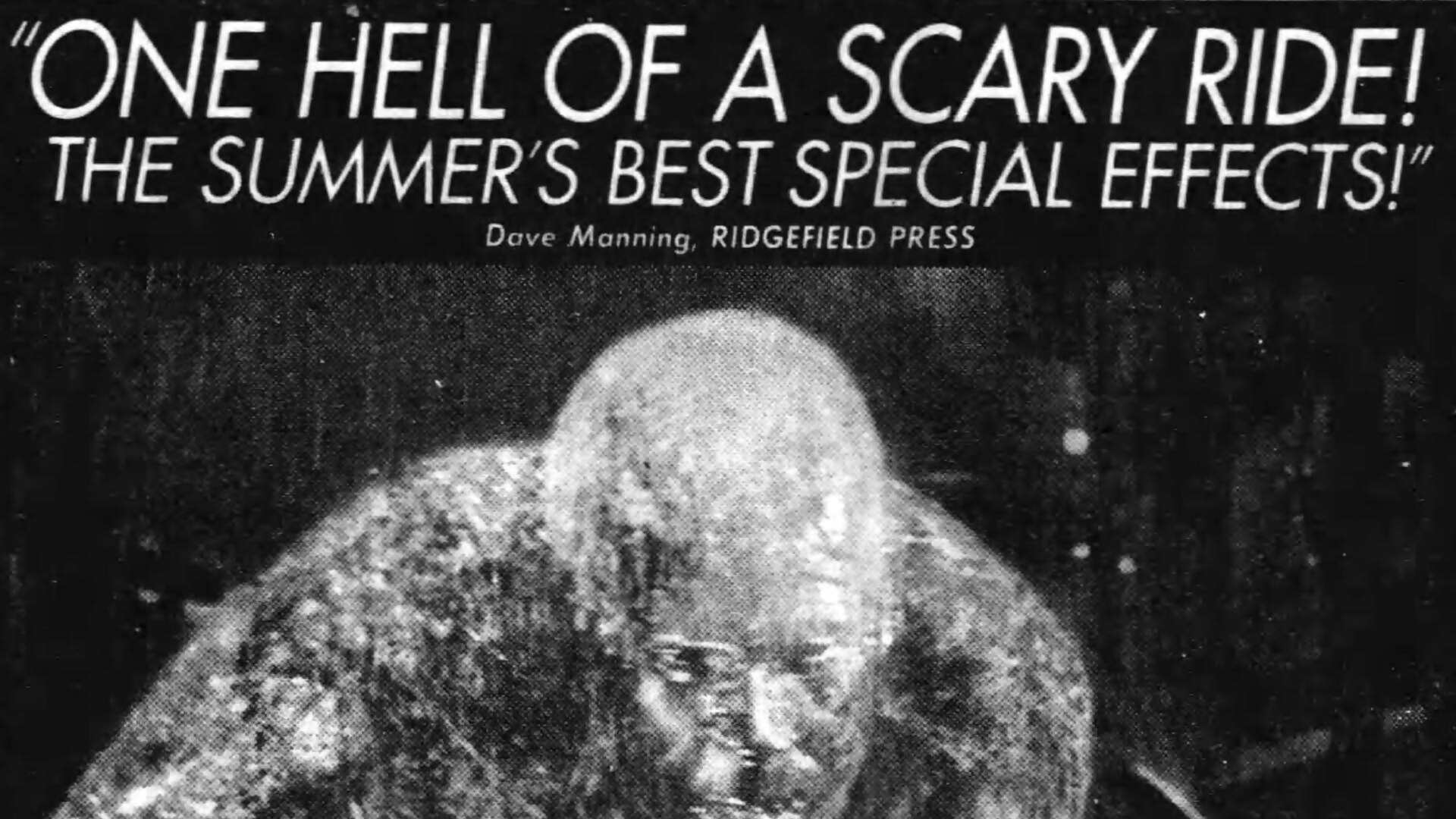

In 2001, whilst legitimate reviewers were tearing apart Rob Schneider's woeful comedy The Animal, one critic stood alone in his effusive praise. David Manning of Connecticut's Ridgefield Press called it "another winner!" He wasn't just kind to Schneider's cinematic car crash, either. Manning adored everything Sony-owned Columbia Pictures released that year. Hollow Man? "One hell of a scary ride!" The Forsaken? "A scary, sexy thrill ride!" A Knight's Tale? Well, Manning reckoned Heath Ledger was "this year's hottest new star."

The man had impeccable taste. Or rather, he would have done—had he actually existed.

David Manning wasn't a film critic at all. He was a marketing executive's fever dream, conjured into existence by Sony's Director of Creative Advertising, Matthew Cramer, who'd grown tired of the laborious process of courting real critics with free screenings and hotel stays, only to receive lukewarm reviews for mediocre films. Why bother with the whole charade when you could simply invent your own critic?

So that's precisely what Cramer did.

The Man Behind the Phantom

The scheme was audacious in its simplicity. Cramer, who'd grown up in Ridgefield, Connecticut, decided to attach his fictional reviewer to the real Ridgefield Press, a small weekly newspaper that Cramer gambled nobody would bother to investigate. He borrowed the name from a mate—a medical equipment salesman who thought having his name in print sounded rather fun and didn't overthink the ethics of the whole affair.

"I didn't look at it as right and wrong," the real David Manning later confessed to The New York Times. "I looked at it as, I was going to see my name in a newspaper. I didn't think ahead."

Between July 2000 and June 2001, Manning's glowing pull quotes appeared in newspaper advertisements across America. Six films. Six raves. Not a critical word amongst them.

Vertical Limit? Brilliant.

The Patriot? Marvellous.

Each endorsement was carefully crafted to sound enthusiastic but vague—the kind of breathless praise you'd find plastered across any film poster, only this time entirely fabricated. Cramer understood that audiences scanning newspaper ads weren't looking for nuanced criticism. They wanted validation that their cinema ticket wouldn't be wasted.

Fake Critic News Clippings

What Cramer didn't account for was John Horn.

The Unravelling

Horn, a Newsweek journalist developing a story about press junket critics, noticed something peculiar about Manning. The supposed critic had praised The Animal before it had even been screened for reviewers. That alone raised eyebrows. But Horn knew the film criticism community well, and he'd never encountered Manning at screenings or industry events. Nobody had.

Curious, Horn rang round Hollywood. Fellow critics hadn't heard of him. Studio publicists drew blanks.

So Horn took the logical next step: he telephoned the Ridgefield Press directly.

"There's no David Manning working here," publisher Thomas Nash told him. The paper employed a father-and-son reviewing team, neither of whom bore that name.

Before Sony could return Horn's subsequent call, the producer of The Animal rang Horn personally, insisting he had nothing to do with any "Dave Manning." This defensive manoeuvre only deepened Horn's suspicions. When he pressed Sony directly about Manning's existence, they came clean.

Horn's exposé landed in June 2001 like a bomb. Sony issued the expected mea culpa, calling it "an incredibly foolish decision" and promising an investigation. Cramer and his boss, Josh Goldstine, received month-long suspensions without pay—hardly the scalps the public demanded, but enough for Sony to claim accountability.

Suggested Read...

The Reckoning

The scandal's timing couldn't have been worse for Sony. That same month, the studio was caught using its own employees in television advertisements for The Patriot, presenting them as regular cinema-goers emerging from screenings. One Sony staffer gushed on camera that Mel Gibson's violent Revolutionary War epic was "a perfect date movie"—surely one of the more questionable romantic recommendations in film history.

Universal and Fox later admitted to similar practices. The entire industry, it seemed, had grown comfortable with deception.

Connecticut Attorney General Richard Blumenthal launched an investigation that culminated in Sony settling for $326,000 in 2002, along with a promise never to fabricate reviews again. But the real blow came from disgruntled filmgoers who filed a class action lawsuit. A judge awarded them $1.5 million, offering $5 refunds to anyone who'd paid to see Vertical Limit, A Knight's Tale, Hollow Man, or The Patriot.

Notably absent from the refund list? The Animal and The Forsaken. Even Sony seemed to accept those films were beyond redemption.

The Federal Communications Commission, which oversees advertising claims, declined to pursue formal action despite labelling the Manning ruse "troublesome." Publisher Nash, believing the scandal hadn't particularly harmed his newspaper, didn't pursue legal action either.

A Symptom of Something Larger

The David Manning affair should have been a wake-up call. Instead, it was a harbinger.

What Sony's marketing department understood—perhaps better than the studio would have liked to admit—was that film criticism was already losing its cultural authority. The elaborate ruse worked because nobody was paying close attention. Manning's reviews appeared alongside legitimate critics' work, and audiences couldn't distinguish between them. They were all just blurbs on a poster.

This wasn't always the case.

For decades, film criticism served as the industry's conscience and the public's guide. Critics like Pauline Kael at The New Yorker commanded seemingly unlimited space to explore cinema's artistic merits with a literacy that earned industry respect. Vincent Canby at The New York Times and Richard Corliss at Time wrote with integrity and insight. Their words mattered not just to readers but to filmmakers.

Then there were Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert, who revolutionised film criticism by making it accessible without sacrificing intellectual rigour. Their syndicated television programme, Siskel & Ebert At the Movies, brought thoughtful discourse into living rooms across America. Ebert's Pulitzer Prize in 1974 validated criticism as serious journalism. Their famous thumbs—up or down—became cultural shorthand, but behind those simple gestures lay genuine expertise.

When Ebert died in 2013, something irreplaceable vanished.

The Void They Left Behind

Ebert himself saw it coming. In a prescient 2008 essay titled "Death to Film Critics! Hail to the CelebCult!", he wrote:

"A newspaper film critic is like a canary in a coal mine. When one croaks, get the hell out."

He was responding to newspapers imposing a 500-word limit on entertainment writers and prioritising celebrity gossip over considered criticism. "The CelebCult virus is eating our culture alive," Ebert warned. "It teaches shabby values to young people, festers unwholesome curiosity, violates privacy, and is indifferent to meaningful achievement."

His words proved prophetic. Major newspapers began sacking experienced film critics en masse. The Detroit Free Press decided it needed no film critic at all. Michael Wilmington left the Chicago Tribune. Jack Mathews and Jami Bernard departed the New York Daily News. The internationally respected Jonathan Rosenbaum retired from the Chicago Reader.

The industry didn't lose critics because audiences stopped caring about films. It lost them because newspapers stopped believing informed opinion mattered more than clicks, gossip, and advertising revenue.

What rushed in to fill the vacuum? Algorithms. Influencers. TikTok reviews lasting thirty seconds.

Recommended For You...

The Algorithm Will See You Now

Today, 26% of viewers rely on streaming algorithms to decide what to watch, surpassing the 23% who trust word-of-mouth recommendations. Film criticism hasn't disappeared—it's been democratised into meaninglessness. Platforms like Rotten Tomatoes aggregate hundreds of opinions into a single percentage, whilst Letterboxd turns everyone into a critic.

This sounds egalitarian until you realise what's been lost.

Where Ebert could dedicate 2,000 words to exploring why a film succeeded or failed, TikTok "critics" offer aesthetic judgements based on costumes and soundtracks. Where Kael could challenge readers to reconsider their assumptions, algorithm-driven recommendations simply feed you more of what you've already consumed. The system isn't designed to expand taste—it's engineered to confirm it.

Studios now invite social media influencers to film premieres instead of journalists, seeking viral moments rather than critical engagement. During 2023's Barbie and Haunted Mansion premieres, film critics voiced frustration on social media about being sidelined for smartphone-wielding content creators whose "reviews" consisted of outfit videos and dance clips.

"It's weird to see influencers do red carpet interviews instead of journalists who have been on their grind for years," independent critic Shannon McGrew tweeted.

The shift isn't merely about platforms. It's about what we've decided criticism should do. Critics once guided audiences towards challenging, rewarding films they might otherwise miss. Now, "criticism" largely exists to validate blockbusters or trash them into viral infamy. The middle ground—thoughtful analysis of mid-budget dramas, foreign films, documentaries—has largely evaporated alongside the critics who championed them.

What We've Lost

The film industry has responded to criticism's decline predictably: by playing it safe. Why risk original storytelling when algorithms and test audiences can tell you exactly what performs? Hence the endless franchises, sequels, and "legacy" follow-ups that dominate cinema. When trusted critics existed to champion bold, original work, studios occasionally took risks. Now, without those guides, audiences cluster around familiar brands.

Perhaps it's fitting, though. Film criticisms' demise mirrors our broader cultural moment rather neatly. We've spent the past decade deciding that expertise is elitism, that all opinions hold equal weight, that feelings matter more than facts. Why trust a critic who's studied cinema for decades when your mate's Instagram story offers just as valid a take? It's the same logic that's given us anti-vaxxers, flat-earthers, eco warriors and people who reckon they've "done their own research" on YouTube. We've democratised knowledge right into ignorance, and cinema was simply an early casualty.

The irony is devastating. Sony invented David Manning because legitimate critics were too harsh on mediocre films. But in a world without respected criticism, everything becomes mediocre. There's no one left with the authority to distinguish greatness from adequacy, to challenge audiences to expect more.

When the real David Manning was finally asked his genuine opinion of The Animal, he admitted: "Not the best movie I've seen."

It's the most honest review the film ever received. And it came far too late.