The 1960s didn't just give us Psycho and The Birds. Beneath Hitchcock's shadow, a generation of filmmakers was quietly rewriting the thriller playbook—experimenting with non-linear storytelling, psychological realism, and visual techniques that modern cinema still mines for ideas.

These films flopped, got buried by poor distribution, or destroyed their directors' careers. Then they became blueprints.

Here are ten 1960s thrillers you've probably never seen that influenced everything from Drive to Black Swan.

Peeping Tom (1960)

Michael Powell's career ended the night this premiered. Critics savaged it. Audiences fled. The film vanished for two decades.

Powell filmed a serial killer who murders women while filming their final moments—making the audience complicit through the camera's gaze. It's the proto-slasher that Halloween and Maniac would build on, decades before "video nasty" became a phrase.

The innovation wasn't just the subject matter. Powell turned the camera itself into a weapon, making cinema's voyeuristic nature the actual horror. Every found-footage film and every "killer's POV" shot owes this film a debt it can't repay.

Martin Scorsese championed its restoration in the 1970s. By then, the damage to Powell's reputation was permanent.

Le Samouraï (1967)

Jean-Pierre Melville's hitman walks through Paris like a ghost. Minimal dialogue. Maximum style. The template for every cool assassin who followed.

Drive's nameless wheelman, John Wick's coded underworld, Ghost Dog's samurai philosophy—they all start here. Alain Delon's Jef Costello established the aesthetic: trench coat, hat, ritualistic precision, existential loneliness.

Melville invented visual minimalism as character psychology. Watch Ryan Gosling in that elevator in Drive—that's pure Melville. Watch Keanu Reeves suiting up in John Wick—same DNA.

The French critics dismissed it as "too American." American critics called it "too French." It flopped everywhere. Then filmmakers discovered it and never stopped stealing from it.

The Collector (1965)

William Wyler adapted John Fowles's novel about a butterfly collector who kidnaps a woman and keeps her in his basement. It's the original "captivity thriller"—the genre template for Silence of the Lambs, Room, and every "stranger in the basement" nightmare that followed.

The innovation was psychological realism. Terence Stamp's Frederick Clegg isn't a monster—he's a lonely man who genuinely believes he can make her love him. That's more terrifying than any slasher because it's recognisably human.

Jonathan Demme studied this film obsessively before making Silence of the Lambs. The power dynamics, the claustrophobic intimacy, the captor's delusional rationality—it's all here first.

Stanley Kubrick was so impressed he hired the cinematographer for 2001: A Space Odyssey.

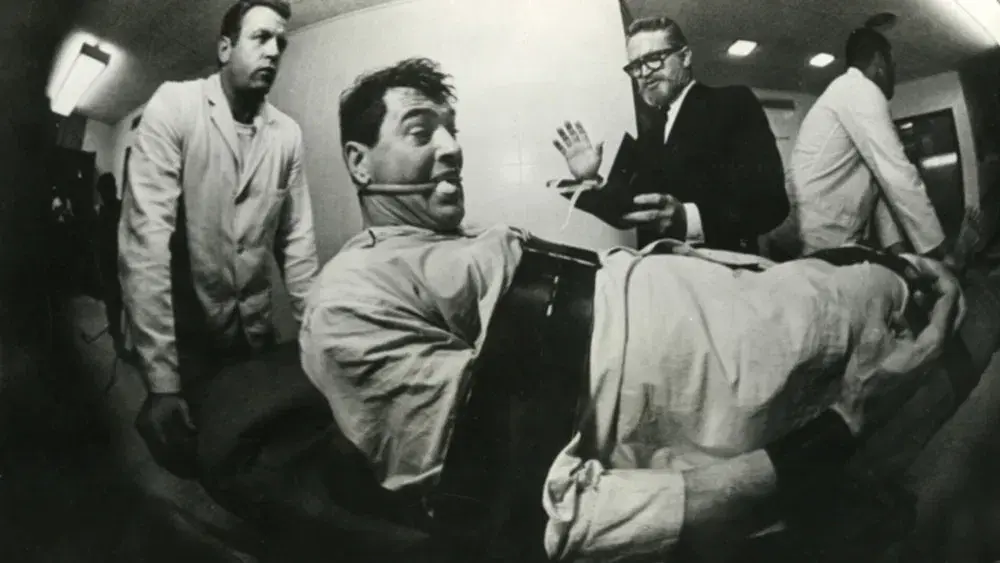

Seconds (1966)

John Frankenheimer's nightmare about a middle-aged banker who fakes his death and gets a new face, new life, new identity. Then realises he's still himself.

This is where body horror meets existential dread. David Cronenberg has cited it repeatedly. The fish-eye lenses, the paranoid framing, the idea that changing your body can't change your soul—Seconds pioneered the visual language of identity horror.

It bombed spectacularly at Cannes. Paramount buried it. Rock Hudson's performance as a man trapped in someone else's face was too raw, too uncomfortable. The studio had no idea how to market existential terror.

Criterion restored it. Now film students study its cinematography. In 1966, audiences just wanted it to stop.

Read Next

From the Vault

Point Blank (1967)

John Boorman's revenge thriller fragments time and reality. Lee Marvin's Walker might be dead, might be dreaming, might be a ghost hunting the men who betrayed him. The film never tells you which.

Christopher Nolan studied this before Memento. Steven Soderbergh called it a masterclass in visual storytelling. The non-linear structure, the subjective reality, the colour-coded nightmare logic—Boorman was experimenting with narrative form that wouldn't become mainstream for another thirty years.

It's also where the "minimalist badass" archetype crystallised. Walker barely speaks. He just walks. And walks. And destroys everything in his path.

MGM thought they'd bought a straightforward crime film. They got French New Wave surrealism dressed as pulp noir. It confused audiences and influenced a generation of filmmakers who grew up watching it on late-night television.

Blow-Up (1966)

Michelangelo Antonioni made a thriller about a photographer who accidentally captures a murder—maybe. The more he enlarges the photograph, the less certain he becomes.

Brian De Palma remade it as Blow Out. Francis Ford Coppola used its paranoid structure for The Conversation. Every conspiracy thriller about ambiguous evidence and unreliable perception traces back to this film.

The innovation was making uncertainty the actual plot. There's no resolution, no clarity, no truth. Just a photographer staring at grainy images that might mean everything or nothing.

Audiences hated it. Critics called it pretentious. Then filmmakers realised Antonioni had invented a new kind of thriller—one where the mystery isn't who did it, but whether anything happened at all.

It won the Palme d'Or. Then disappeared from cinemas within weeks.

Repulsion (1965)

Roman Polanski's first English-language film follows a young woman's psychological collapse in a London apartment. The walls crack. Hands reach through. Reality fragments.

Black Swan, Joker, mother!—the "subjective horror breakdown" subgenre starts here. Polanski films Catherine Deneuve's descent with suffocating intimacy, making the audience experience her deteriorating mental state rather than observe it.

The apartment itself becomes a character, a womb, a trap. Darren Aronofsky has cited it as the template for psychological horror where the protagonist's mind is the real threat.

It's Polanski's best film. Most people have never heard of it because Rosemary's Baby overshadowed everything that came before.

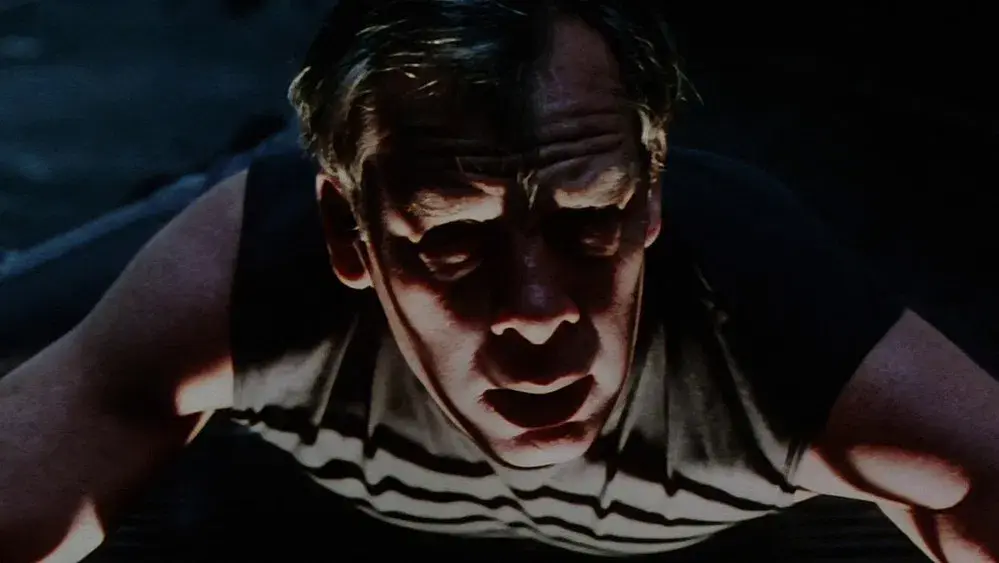

Shock Corridor (1963)

Samuel Fuller's pulp masterpiece about a journalist who fakes insanity to solve a murder inside an asylum, then actually goes insane. It's lurid, garish, deliberately excessive—and Scorsese called it one of the most influential films he'd ever seen.

Shutter Island, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, every "sane person in an insane system" thriller traces back to Fuller's asylum nightmare. The expressionist colour sequences, the inmates representing America's social traumas, the reporter's gradual loss of self—it's all here.

Fuller shot it in ten days on leftover sets. Critics dismissed it as exploitation trash. Then filmmakers discovered it and realised Fuller had invented a visual language for institutional madness that nobody had matched.

The Naked Kiss (1964)

Fuller's follow-up opens with a prostitute beating a man with her handbag while the camera shakes violently. It's the most confrontational opening in 1960s cinema.

Quentin Tarantino has cited Fuller obsessively. The pulp aesthetics, the moral ambiguity, the sudden violence, the way Fuller refuses to let audiences feel comfortable—it's all Tarantino DNA.

The film was considered too raw, too ugly, too honest about American hypocrisy. It vanished. Then filmmakers who grew up on late-night TV discovered Fuller's brutal poetry and never forgot it.

It's still shocking. That's why it still works.

Mirage (1965)

Edward Dmytryk's amnesia thriller about a man who can't remember the last two years—or why people keep trying to kill him. It's the template for every conspiracy thriller from The Bourne Identity to Unknown.

The innovation was making amnesia the narrative engine, not just a plot device. The audience experiences the confusion in real time. No flashbacks, no explanations, just a man piecing together his identity while running for his life.

It flopped because audiences found it too confusing. Then The Bourne Identity used the exact same structure and made half a billion dollars.

Gregory Peck's blank-faced paranoia influenced every amnesiac protagonist who followed. The film just needed another forty years for audiences to catch up.

The Influence Never Stopped

These films didn't fail at the time because they were bad. They failed because they were too early.

Audiences in the 1960s wanted clear heroes, obvious villains, and tidy resolutions. These directors offered ambiguity, paranoia, and psychological complexity. So the films flopped, careers ended, and Hollywood moved on.

Then a generation of filmmakers discovered them on television and in art house revivals. They saw the experiments, the innovations, the risks. And they built modern thriller cinema on those forgotten foundations.

You've seen their influence in dozens of films. Now you know where it came from.