Everyone's praising Guillermo del Toro's 2025 Frankenstein as the definitive adaptation. I walked out disappointed. Not because it's badly made—it's gorgeous—but because after 30 years, we finally got another big-budget Frankenstein, and somehow it's less faithful than Kenneth Branagh's maligned 1994 version that everyone loves to mock.

And it all comes down to one man: Frank Darabont.

The Script Nobody Talks About

While film critics heap praise on Guillermo del Toro's lavish 2025 Frankenstein adaptation, there's a crucial piece of history they're ignoring: both del Toro's film and Kenneth Branagh's supposedly "failed" 1994 version share a common DNA in Frank Darabont's phenomenal 1993 screenplay. Branagh hired Darabont to write it. Del Toro, years later, called it "pretty much perfect" and incorporated its elements into his own script—all while claiming Branagh never properly filmed it.

Yes, that Frank Darabont. The man who gave us The Shawshank Redemption (released the same year as Branagh's Frankenstein), The Green Mile, and The Walking Dead. In 1993, Darabont wrote what he himself called "the best script I ever wrote and the worst movie I've ever seen."

He was talking about Branagh's film.

But here's the twist: del Toro's 2025 version, for all its critical acclaim, strays even further from what made Darabont's screenplay exceptional. And in doing so, it betrays Mary Shelley's original vision more profoundly than Branagh's over-the-top melodrama ever did.

What Darabont Got Right

Darabont's February 1993 revised draft is a masterclass in Gothic tragedy. Here's what makes it exceptional:

Structure and Pacing:

- Opens with Captain Walton's Arctic expedition encountering Victor Frankenstein (straight from Shelley)

- Flashes back through Victor's entire story—childhood romance with Elizabeth, mother's death, education at Ingolstadt, Professor Waldman's murder, and the catastrophic creation

- Patient storytelling that whispers rather than shouts

- Builds Victor and Elizabeth's relationship over decades using a recurring waltz motif—from childhood dance lessons to their wedding night

The Creature's Development:

- Gives the Creature genuine pathos as he learns to read, speak, and understand humanity

- Shows his education through secret observations of Felix's peasant family (directly from the novel)

- Captures his transformation from innocent to monster through rejection and suffering

The Creation Itself:

- Gets the Creature right: a botched experiment, not a misunderstood innocent

- Victor's first words upon seeing his creation: "What have I done?"

- His journal entry is damning: "Massive birth defects. Result is malfunctional and vile. Have chosen to abort."

- The Creature is described with visceral disgust: "ghastly gray skin rippling with harsh ligaments and sinewy veins, brutal surgical scars"

- Victor doesn't reject his creation out of cruelty—he rejects it because it's genuinely horrifying

The Ending:

- Uncompromising and nihilistic

- Victor pursues the Creature to the Arctic, dies aboard Walton's ship after confessing his crimes

- The Creature—overcome with grief and rage—immolates himself and Victor's corpse together on a funeral pyre

- No redemption. No forgiveness. Just consequences.

How Branagh Broke It

Kenneth Branagh's 1994 film kept Darabont's structure but destroyed its soul through sheer velocity. Roger Ebert praised Robert De Niro's performance as the Creature but noted the film "doesn't pause to be sure its effects are registered." Multiple reviews described it as feeling like a three-hour movie hacked down to two, with quiet character moments sacrificed for operatic bombast.

Branagh's additions didn't help. He insisted on "explicitly sexual birth images" during the creation sequence and added the notorious resurrection of Elizabeth as Victor's bride—a sequence that plays as unintentional camp in the final film, with Victor waltzing his stitched-together dead wife around the laboratory while Justine's severed head watches from a formaldehyde jar.

On the page, this sequence is Gothic tragedy. On screen, it became the film's most mockable moment.

Original screenwriter Steph Lady later revealed that a USC film professor used the screenplay as a teaching tool to demonstrate "what can happen to a good script in the hands of a bad director."

Yet for all these failures, Branagh understood something crucial: the Creature must be genuinely monstrous for the tragedy to work. We'll return to this.

How Del Toro Betrayed It

Del Toro's ending abandons Shelley's nihilism for Hallmark redemption. Victor and the Creature reconcile aboard Walton's ship. Victor acknowledges the Creature as his son and begs forgiveness. They embrace. Victor dies at peace. The Creature then—and this is the kicker—frees Walton's ship from the ice using his superhuman strength and walks off into the Arctic sunset with an implied hopeful future ahead.

This isn't adaptation. It's sanitisation.

Worse, del Toro gives the Creature "advanced healing factor" abilities that make him essentially immortal. In Shelley's novel, the Creature walks off to build his own funeral pyre, choosing death now that his creator is gone. In Darabont's script, he literally burns himself alive while cradling Victor's corpse, "shrieking revenant wrapped in a caul of fire... Still cradling Victor. Still screaming."

Del Toro's Creature can't die. He's functionally a superhero. The entire tragedy evaporates because there are no permanent consequences for anyone.

But his most fundamental failure runs deeper than the ending—it's the Creature itself.

The Creature: Where Everything Hinges

Here's what many critics miss when comparing these films: everything in Frankenstein rises or falls on a single question—does Victor's horror at his creation make sense?

If the Creature is genuinely monstrous, Victor's rejection is tragic but understandable. The story becomes about consequence and responsibility.

If the Creature looks like a deliberately designed art piece rather than a failed experiment, Victor's rejection is inexplicable cruelty. The story becomes about prejudice and learning to love the different.

One is Mary Shelley's novel. The other is del Toro's fanfiction.

Del Toro's Porcelain Mistake

Mike Hill spent nine months creating Jacob Elordi's makeup using 42 silicone prosthetics to achieve a deliberately geometric aesthetic based on 19th-century anatomy books. The goal was to make the Creature look like a marble statue with precise patterns—sympathetic, vulnerable, and "closer to prayer than horror."

It's accomplished work. It's also completely wrong.

If your Creature is designed to look like a sculptural art piece from frame one, Victor's rejection becomes inexplicable. Oscar Isaac's Frankenstein looks like a monster for abandoning something that's more Nebula from the Avengers than failed medical experiment. The audience can't understand his horror because there's nothing viscerally wrong about Elordi's smooth, geometric features and deliberately sculpted physique.

The design is too clean, too intentional, too aesthetically pleasing. It looks like Victor succeeded in creating something—not like he botched it.

Worse, del Toro's decision to give the Creature advanced healing abilities means any initial grotesqueness fades rapidly. The scars heal. The damage repairs itself. The visceral horror that might have justified Victor's rejection literally disappears from the screen, leaving us with an increasingly smooth, geometric figure that becomes less monstrous as the film progresses.

Then there's the matter of Elordi's performance. His Creature starts with guttural, broken speech—mimicking De Niro's approach—but rapidly evolves throughout the film into Shakespearean eloquence, as if his linguistic abilities have the same supernatural healing factor as his scars. By the film's end, he's delivering theatrical monologues with perfect diction and posh elocution, completely at odds with someone who learned to speak mere months ago by eavesdropping through a pigsty wall.

And here's the final absurdity: by the film's conclusion, Elordi's Creature has transformed into a gothic romance hero—flowing hair, sharp jawline, perfect teeth. He looks less like a reanimated corpse and more like Flynn Rider from Tangled preparing to do his smolder. I half-expected him to sweep someone off their feet rather than inspire terror.

It's refined. Sophisticated. And like the healing scars, it makes the Creature progressively less monstrous and more acceptable as the film continues—exactly the opposite of what the tragedy requires.

Branagh's Visceral Truth

Compare this to De Niro's Creature in Branagh's film: a shambling, malformed being who speaks in broken, guttural sentences because he's literally learning language from scratch. His teeth are rotted. His voice is rough. His movements are uncoordinated. He looks and sounds like what he is—a reanimated corpse, not a gentleman caller!

Daniel Parker's makeup effects were visceral, genuinely unsettling work that made Victor's revulsion believable. You understood why Victor fled. You understood why the peasants attacked him with torches. You understood why Felix beat him with a fireplace poker.

De Niro's performance captures the Creature's tortured intelligence and capacity for both tenderness and rage. When he murders young William, it's an act of blind fury that he immediately regrets—exactly as Shelley and Darabont intended. The Creature isn't a sympathetic innocent. He's a broken, dangerous being capable of monstrous acts, and De Niro plays him with appropriate menace.

Why This Matters

Del Toro's Creature inspires sympathy, not horror—but worse, it looks deliberately designed rather than horrifyingly botched. That's a fundamental misreading of Shelley's novel, where the Creature's appearance is meant to be so repulsive that even his creator can't bear to look at him.

Remember Darabont's script description:

"ghastly gray skin rippling with harsh ligaments and sinewy veins, brutal surgical scars."

Victor's first words: "What have I done?" His journal: "Massive birth defects. Result is malfunctional and vile."

This is a botched experiment, not a misunderstood innocent. Victor's horror isn't prejudice—it's the natural human reaction to having violated the laws of nature and created something genuinely wrong.

When you soften the monster, you lose the tragedy. Del Toro made The Shape of Water wearing 19th-century clothes—a love story about accepting the different. That's a beautiful theme for other films. It's not Frankenstein.

Branagh's Creature is what Shelley described: a being so horrifying that its very existence is an affront to nature. That's why his film, despite all its flaws, works as tragedy. Del Toro's Creature is too sculptural, too aesthetically designed, too deliberately constructed. That's why his film, despite all its technical excellence, fails as Frankenstein.

More Deep Dives from RewindZone

Alien 3: Fincher's Divisive Debut

How studio interference shaped a visionary's first film

Film ExplainedThe Sweet Hereafter (1997)

Atom Egoyan's devastating exploration of trauma and memory

Oscar ControversyHow Ordinary People Beat Raging Bull

The 1981 Best Picture race that still sparks debate

Cult ClassicDonnie Darko Explained

Complete analysis of Richard Kelly's time-loop masterpiece

The Paradox and The Auteurs

Here's what makes both failures fascinating: neither director was hamstrung by studio interference or budget constraints. Both had access to Darabont's exceptional screenplay. Both had the creative freedom to film it faithfully.

And both chose not to.

This isn't about meddling executives forcing changes. This is about auteur ego overriding material fidelity.

Kenneth Branagh is Shakespearean to his core. Everything must be operatic, grand, theatrical. He directed himself as Victor like he's playing Hamlet - all passion and fury and doomed nobility. That's his brand. But Frankenstein isn't Shakespeare. It whispers, it doesn't shout. Branagh couldn't help himself. His instinct is always to GO BIGGER, even when the material demands restraint.

Guillermo del Toro is a romantic who makes monsters sympathetic. The Shape of Water won him an Oscar for a love story between a mute woman and a fish creature. His entire career argues that monsters deserve love, understanding, redemption. That's his signature. But Frankenstein's Creature isn't meant to be redeemed. He's meant to be damned alongside his creator.

Both directors imposed their auteur brands even when the script demanded something different.

But there's a crucial distinction between them.

Branagh's failure is execution. He botched the delivery through over-the-top performances, rushed pacing, and campy melodrama. But he never changed Darabont's nihilistic core. Victor and his Creature remain doomed. There's no redemption, no healing, just consequences spiraling toward mutual destruction.

Del Toro's failure is calculation. He had complete creative control at Netflix. No one forced him to soften the ending. No executive memo demanded a redemptive arc. He chose to give 2025 audiences what they wanted: a therapeutic father-son journey where forgiveness heals all wounds.

That's not compromise. That's pandering.

But 2025 is the therapy culture era. "Healing your inner child." "It's okay to not be okay." Redemption arcs. Emotional resolution. Del Toro gave modern audiences Frankenstein as a mental health journey where the traumatised Creature just needs his father's love to become whole.

Branagh's nihilistic version would get destroyed in 2025. They'd call it "trauma porn" and criticise the lack of emotional healing.

Del Toro saw what contemporary audiences craved and delivered it. He had the freedom to film Darabont's dark ending where both creator and creation burn together in damnation. He chose not to because it wouldn't play well to a generation that needs everything to end in understanding.

The paradox is this: both directors failed because they had too much freedom. Sometimes constraints force discipline. Sometimes you need someone in the room saying "just film what Darabont wrote."

Neither had that person. And Shelley's tragedy paid the price.

The Audience Divide

Look at user reviews and the split becomes clear. Branagh's film has its passionate defenders who call it "quite simply spectacular" and praise De Niro for bringing out "genuine pity, sorrow, and most importantly, fear." But critics slam it as "far too worthy" with pacing that makes the film feel "heavy and even dull."

Del Toro's version gets similar treatment. Enthusiasts declare it "easily one of the most faithful adaptations ever made," praising the visuals and performances. But dissenters push back hard, arguing that viewers "have clearly never seen the 1994 Branagh version, which was far superior on all score: pacing, cast and direction."

The interesting pattern? Those defending Branagh's film consistently point to De Niro's performance and the genuine horror. Those defending del Toro's point to its technical accomplishment and visual beauty.

Nobody's arguing about which one captured Shelley's nihilistic tragedy. Because Branagh's film, for all its flaws, never forgot that Victor's creation must end in damnation, not redemption.

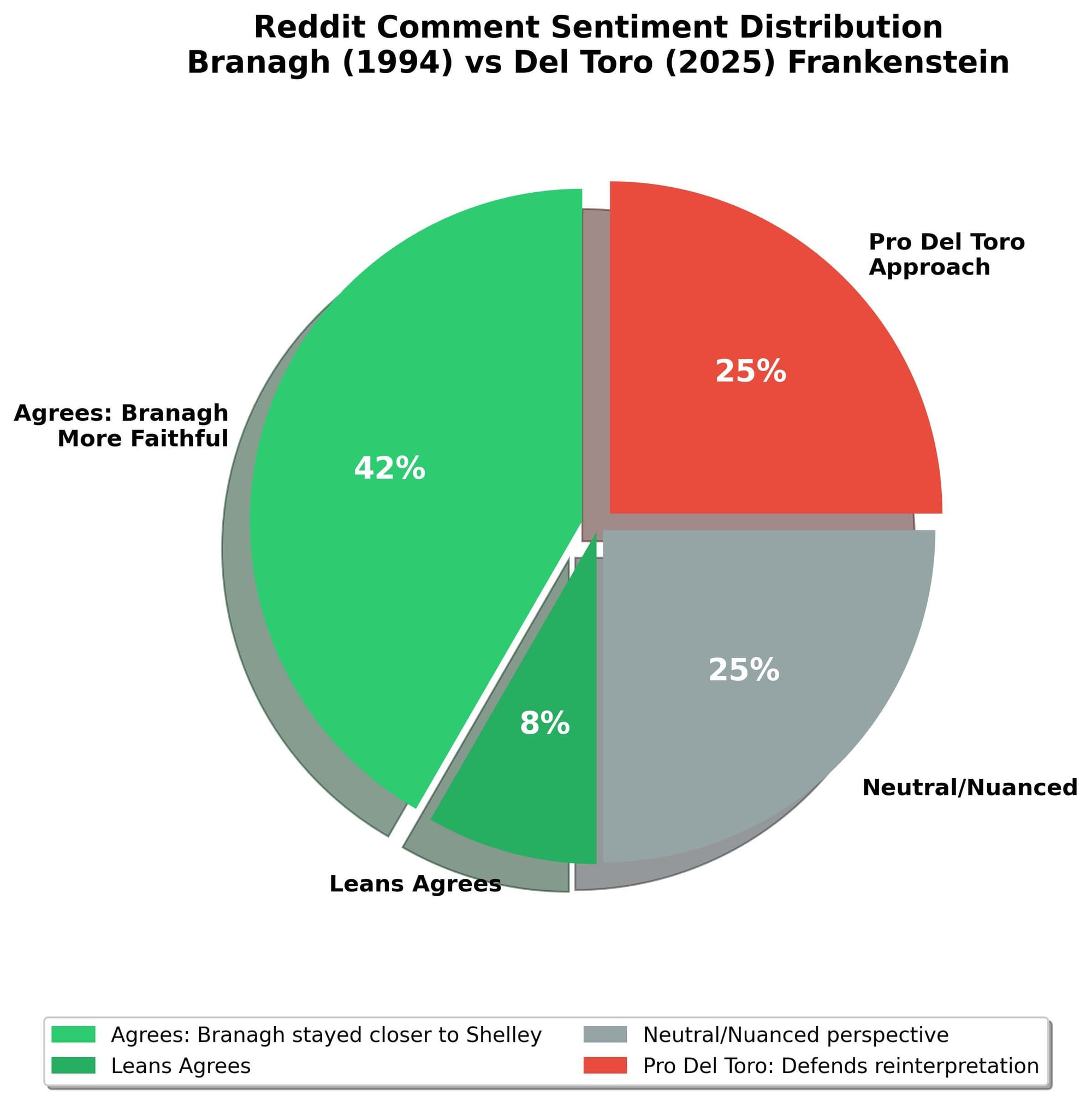

I took to Reddit to get the views from r/TrueFilm...

Branagh's 1994 Frankenstein vs del Toro's 2025 version - some thoughts on faithfulness to Shelley's novel

by u/TheRewindZone in TrueFilm

Data Analysis from Reddit comments:

Look, I think debates are only worthwhile if we actually understand where people stand. So I went through all the comments here (excluding my own) and broke down the positions. What's the point of having a discussion if we don't look at what we're actually agreeing or disagreeing on?

Results:

- 50% agree that Branagh stayed closer to Shelley's nihilistic tragedy (despite his execution being a mess)

- 25% defend del Toro's approach

- 25% sit somewhere in the middle with nuanced takes

Breaking it down further:

- Strongly agrees with my thesis: 41.7%

- Leans agrees: 8.3%

- Neutral/sees merit in both: 25%

- Pro del Toro/disagrees: 25%

Points where we seem to agree: Victor's immediate horror is crucial to Shelley's story, del Toro's redemptive ending contradicts the novel's nihilistic core, the Creature's progressive healing changes the moral framework, and del Toro made something closer to his own story than Shelley's.

The strongest counter-arguments: faithfulness isn't automatically valuable—bold reinterpretation can be better; Shelley actually describes the Creature with beautiful features (lustrous hair, white teeth); del Toro's themes about generational trauma resonate with modern audiences; and a less hideous Creature makes Victor's rejection worse, not better.

What's interesting is that even people who prefer del Toro's film mostly acknowledge it diverges from Shelley's themes. The real debate isn't about which film is more faithful—it's about whether faithfulness matters. That's a different argument entirely, and honestly, a valid one. The counterpoints about adaptation philosophy are worth considering.

The Verdict

I should love Guillermo del Toro's Frankenstein. I've defended his monsters-deserve-love philosophy in every other film he's made. The Shape of Water moved me. Pan's Labyrinth devastated me.

But here, that philosophy betrays Mary Shelley's novel.

Frank Darabont wrote the definitive Frankenstein screenplay in 1993. It was faithful to Shelley's structure, captured her themes of creation and consequence, and understood that Gothic tragedy means nobody gets a happy ending.

Two directors tried to film it. Both failed, but only one kept faith with the source material's darkness. Branagh's film is flawed—loud, rushed, melodramatic. The bride sequence is campy. The pacing is suffocating. I won't pretend otherwise.

But it never forgets that Victor Frankenstein's sin demands punishment, not redemption.

Del Toro's film is more accomplished on every technical level. The cinematography is breathtaking. The production design is immaculate. Jacob Elordi gives a committed performance. But technical excellence doesn't equal thematic fidelity.

Critics praising del Toro's 2025 Frankenstein as the definitive adaptation are mistaking beauty for truth. Yes, it's stunning. Yes, it's restrained. Yes, it's emotionally satisfying.

But satisfaction isn't the point. Shelley's novel isn't about fathers and sons learning to forgive each other. It's about the catastrophic consequences of playing God without accepting responsibility. It's about how the sins of the creator corrupt the creation. It's about how some mistakes can't be fixed, some crimes can't be atoned for, and some monsters—both literal and figurative—can never be redeemed.

Darabont understood that in 1993.

Branagh understood it in 1994, even if his execution was deeply flawed.

Del Toro, for all his decades of devotion to Shelley's text, traded tragedy for therapy. He gave 2025 audiences the Frankenstein they wanted—not the one Shelley wrote.

The best Frankenstein film ever made was written in 1993. Kenneth Branagh came closer to filming it than Guillermo del Toro did, even though both missed the mark.

We're still waiting for someone to get it right.

Fancy Purchasing and helping our website?

What are your thoughts? Did Branagh's 1994 Frankenstein deserve its critical drubbing? Does del Toro's 2025 version really capture Shelley's vision? Let us know in the comments.