Linda Fiorentino didn't just act in films—she dominated them. From her breakthrough as the ultimate femme fatale in The Last Seduction to her enigmatic turn opposite Will Smith in Men in Black, she carved out a 90s career defined by intelligence, sexuality, and an unwillingness to play by Hollywood's rules.

Then, almost as suddenly as she'd arrived, she was gone.

By 2009, after two decades of provocative work spanning Scorsese's Manhattan nightmares to Kevin Smith's religious satire, Fiorentino had effectively retired from acting. Whispers of on-set conflicts, a reputation for being "difficult," and entanglement in the Anthony Pellicano wiretapping scandal contributed to her disappearance from screens. The industry that had celebrated her raw talent in the mid-90s seemed content to let her fade into obscurity.

But before the exit, she left behind a filmography that rewards excavation. This isn't a ranking of Linda Fiorentino's best films—several entries here are critically panned or commercially forgotten. This is a ranking of her best performances, moments where her screen presence elevated material, challenged conventions, or revealed dimensions of talent that mainstream Hollywood never fully utilised.

From her feature debut in Vision Quest to her career-defining turn in The Last Seduction, here are Linda Fiorentino's 10 greatest performances.

10. What Planet Are You From? (2000)

Director: Mike Nichols

Genres: Science Fiction, Comedy, Romance

Main Cast: Garry Shandling, Annette Bening, Greg Kinnear, Linda Fiorentino, John Goodman, Ben Kingsley

Mike Nichols' sci-fi sex comedy about an emotionless alien (Garry Shandling) sent to Earth to impregnate a human is tonally confused and critically savaged. It's a bizarre late-career entry for the director of The Graduate.

Yet Linda Fiorentino makes her limited screen time count. As Helen Gordon, a seductive AA sponsor, she brings the same knowing sexuality that defined The Last Seduction—but calibrated for broad comedy. She's playing a deliberately shallow archetype whose entire identity revolves around surface-level attraction, and Fiorentino leans into the satire without winking.

Watch how she commands scenes opposite Shandling's deliberately flat affect. She's the only performer who seems to understand the film's attempted commentary on human connection versus physical conquest. The performance is competent rather than revelatory, which is why it lands at number ten, but even Fiorentino on autopilot is more interesting than most actresses at full throttle.

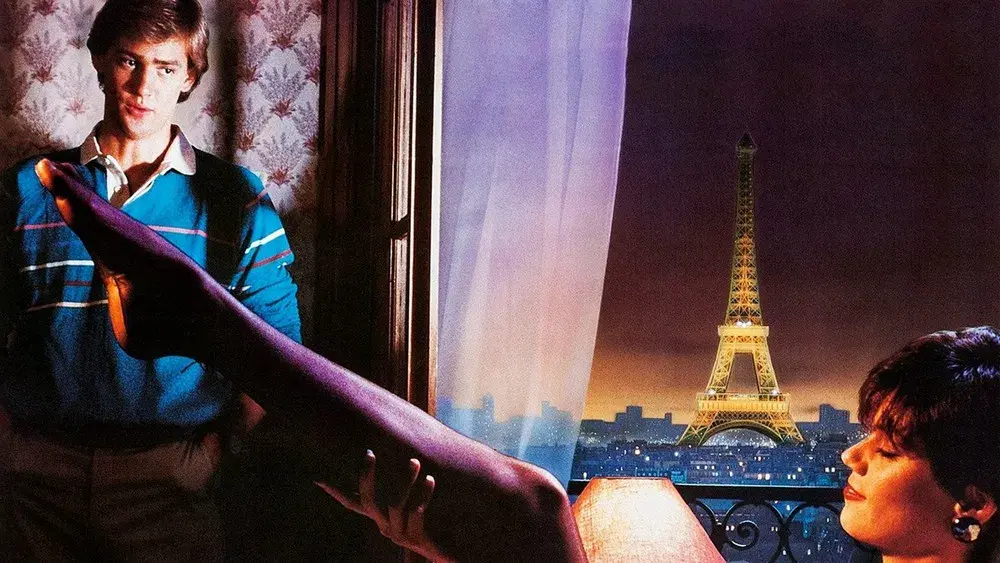

9. The Moderns (1988)

Director: Alan Rudolph

Genres: Drama, Romance

Main Cast: Keith Carradine, Linda Fiorentino, Geneviève Bujold, Geraldine Chaplin, Wallace Shawn

Alan Rudolph's impressionistic drama about American expatriates in 1920s Paris should showcase Linda Fiorentino's range. As Rachel Stone, the ex-wife of a struggling artist (Keith Carradine) now married to a wealthy collector, she's playing wounded vulnerability rather than predatory confidence.

The problem is Rudolph's deliberately opaque storytelling never quite allows Fiorentino to land emotionally. She's lovely to watch, moving through gorgeously composed frames with melancholy grace, but The Moderns is more interested in mood than character psychology.

Still, there are moments. Watch the scene where she reconnects with her ex-husband—Fiorentino conveys years of regret and lingering attraction without dialogue, letting her eyes do the work. It's subtle, intelligent work that suggests she could have thrived in European art cinema.

This ranks at number nine because it's more promise than fulfilment. Three years after Vision Quest, six years before The Last Seduction—a beautiful but frustratingly opaque stepping stone.

8. Gotcha! (1985)

Director: Jeff Kanew

Genres: Action, Comedy, Romance, Thriller

Main Cast: Anthony Edwards, Linda Fiorentino, Nick Corri, Alex Rocco

Linda Fiorentino's first lead role is in a deeply silly Reagan-era action-comedy about a college student (Anthony Edwards) who gets seduced by a mysterious European woman—Fiorentino as Sasha Banicek—who drags him into genuine Cold War espionage.

Yet Fiorentino, fresh out of drama school, is magnetic. Director Jeff Kanew clearly cast her for the role that would become her trademark: the seductive enigma who may or may not be trustworthy. She has to convince both Edwards' character and the audience that she's simultaneously vulnerable and dangerous, and she manages it through sheer presence.

What's remarkable is how assured she is. When she seduces Edwards on a train, she's in complete control. When she later reveals layers of deception, she modulates without losing the character's mystery.

Gotcha! isn't a good film, but it's essential for understanding Fiorentino's trajectory. Every element that would make her perfect for The Last Seduction nine years later is already present: intelligence behind sexuality, refusal to play victim, the ability to wrong-foot male characters and audiences simultaneously.

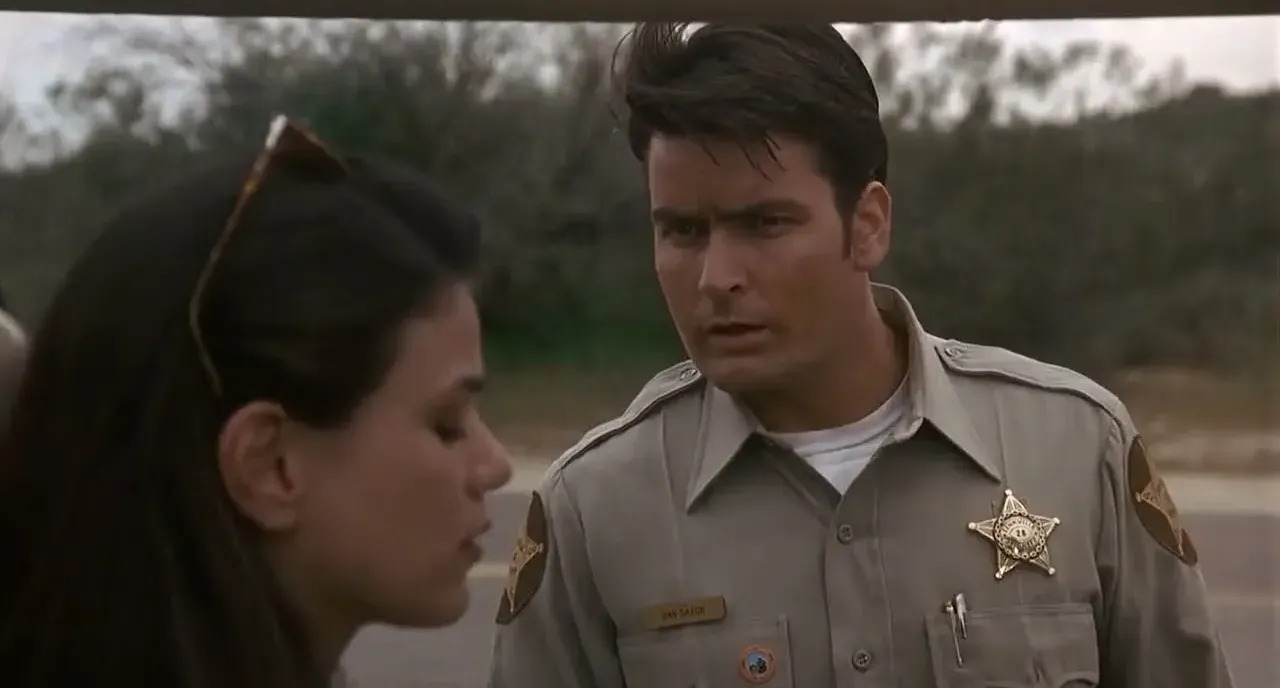

7. Beyond the Law (1992)

Director: Larry Ferguson

Genres: Crime, Drama, Thriller

Main Cast: Charlie Sheen, Linda Fiorentino, Michael Madsen, Courtney B. Vance

This undercover cop thriller is exactly the kind of mid-budget, straight-to-video fare that populated rental shelves in the early 90s. Charlie Sheen infiltrates a biker gang, with Linda Fiorentino as Renee Jason, the volatile girlfriend of the gang leader (Michael Madsen) who becomes Sheen's romantic interest.

It's formulaic territory, but Fiorentino elevates it. She's playing a woman trapped in an abusive relationship, and she refuses to make Renee either pure victim or one-dimensional femme fatale. Watch how she calibrates differently in scenes with Madsen versus Sheen—around the former, she's constantly calculating, adapting to survive. Around the latter, she cautiously allows vulnerability.

The film doesn't deserve her commitment, but Fiorentino finds small moments of truth. When Renee realises Sheen's true identity, her reaction isn't melodramatic betrayal—it's exhausted resignation, as if one more layer of male deception is exactly what she anticipated.

This ranks at number seven because it demonstrates Fiorentino's ability to find psychological complexity in underwritten material. Two years before The Last Seduction, she's already exploring the intersection of female sexuality, masculine violence, and survival strategies.

Read Next

From the Vault

6. After Hours (1985)

Director: Martin Scorsese

Genres: Black Comedy, Thriller

Main Cast: Griffin Dunne, Rosanna Arquette, Verna Bloom, Tommy Chong, Teri Garr, John Heard, Cheech Marin, Catherine O'Hara, Linda Fiorentino

Linda Fiorentino has maybe ten minutes of screen time in Martin Scorsese's nightmarish Manhattan odyssey, but she makes every second count. As Kiki Bridges, an ice-cream-truck-driving sculptor with unconventional sexual interests, she's one of many eccentric characters Griffin Dunne encounters during his increasingly surreal night in SoHo.

This is pure character work. Fiorentino doesn't have a narrative arc—she appears, propositions Dunne's protagonist with matter-of-fact directness about her desire for bondage scenarios, then exits the film. But she creates a complete, specific human being in that brief window. Kiki isn't a punchline or a male anxiety fantasy. She's a sexually confident artist who knows exactly what she wants and sees no reason to apologise for it.

Watch the scene where she matter-of-factly discusses her sculpture while simultaneously making explicit sexual propositions. Fiorentino plays it completely straight, no winking, no signalling to the audience that we're supposed to find this absurd. That commitment is what makes it funny—and slightly terrifying for Dunne's increasingly unravelled character.

This ranks at number six because it's a supporting role in an ensemble piece, but it's also a perfect demonstration of Scorsese's eye for casting. He saw something in Fiorentino—the combination of beauty, intelligence, and absolute fearlessness—that would become her signature. She's not playing "sexy woman" or "quirky artist." She's playing a specific, confident, slightly dangerous individual who happens to be both those things.

It's also worth noting that Scorsese directed her in her feature film debut year (1985) alongside Harold Becker (Vision Quest) and Jeff Kanew (Gotcha!). Three directors, three completely different characters, all in the same year. That's not luck. That's range.

5. Vision Quest (1985)

Director: Harold Becker

Genres: Drama, Romance, Sport

Main Cast: Matthew Modine, Linda Fiorentino, Michael Schoeffling, Ronny Cox, Harold Sylvester, Charles Hallahan

Linda Fiorentino's feature film debut is a supporting role in a wrestling movie. On paper, that shouldn't be the foundation for two decades of provocative performances in neo-noir and independent cinema. Yet Vision Quest is where it all begins, and rewatching it now, you can see exactly why casting directors couldn't look away.

As Carla, a twenty-year-old artist passing through Spokane who temporarily lodges with the family of high school senior Louden Swain (Matthew Modine), Fiorentino is playing the classic coming-of-age archetype: the older woman who introduces the virginal protagonist to adult sexuality and emotional complexity. It's a role that could easily collapse into male fantasy—the sophisticated drifter who exists primarily to facilitate the hero's growth.

But Fiorentino refuses that reduction. She gives Carla a complete interior life. In scenes where Modine isn't present, watch how she interacts with his father, how she moves through the working-class spaces of the household. She's not performing "mysterious seductress" for Louden's benefit. She's a specific person with a specific history—someone who's left something behind, someone who's not entirely sure where she's going, someone who's simultaneously confident and wounded.

The age gap could be creepy, but Fiorentino and Modine have genuine chemistry. More importantly, Fiorentino plays the relationship as mutual discovery rather than corruption. She's not a Mrs Robinson figure using the boy for amusement. She's a young woman who's been hardened by experience, surprised to find genuine connection with someone whose earnestness hasn't been destroyed yet.

This ranks at number five because it's still fundamentally a supporting role in someone else's coming-of-age story. But it's also the first demonstration of what would become Fiorentino's greatest strength: the ability to suggest depth and history through minimal dialogue, to create three-dimensional women in roles that could be sketches.

Director Harold Becker saw it. Scorsese saw it. The casting directors who'd hire her for The Last Seduction saw it. Straight out of drama school, with no screen experience, Linda Fiorentino walked onto set and commanded attention.

4. Dogma (1999)

Director: Kevin Smith

Genres: Comedy, Fantasy, Adventure

Main Cast: Linda Fiorentino, Ben Affleck, Matt Damon, Salma Hayek, Jason Lee, Alan Rickman, Chris Rock, Jason Mewes, Kevin Smith, Alanis Morissette

Kevin Smith's religious satire is messier than his View Askewniverse entries Clerks and Chasing Amy, overstuffed with theological debates and dick jokes in roughly equal measure. It's also the film where Linda Fiorentino had to carry an ensemble comedy on her shoulders, playing the straight woman to fallen angels, stoner prophets, and a shit demon named Golgothan.

As Bethany Sloane, a disillusioned abortion clinic worker who discovers she's the last scion—the final human descendant of Jesus Christ—tasked with preventing two renegade angels (Ben Affleck and Matt Damon) from exploiting a loophole in Catholic theology that would unmake existence, Fiorentino is playing existential crisis amid chaos.

Here's what makes the performance work: she never condescends to the material. Smith's dialogue is self-consciously verbose, characters delivering mini-essays about Catholic doctrine while navigating supernatural slapstick. A lesser actress would signal ironic distance, letting the audience know she's above this. Fiorentino plays it completely grounded. When Bethany questions her faith, when she reacts with rage to learning she's a genetic pawn in a cosmic game, when she ultimately accepts her impossible mission, Fiorentino treats it with the same seriousness she brought to neo-noir.

That commitment is what makes Dogma function. We believe Bethany's crisis because Fiorentino believes it. We invest in her journey because she never betrays the character's emotional reality, even when surrounded by Jay and Silent Bob selling drugs in a Mooby's parking lot.

This ranks at number four—higher than films where she had less to do, lower than her absolute career peaks—because it's the broadest performance in her filmography. She's still magnetic, still intelligent, still refusing to play by conventional rules. But Dogma is also where the whispers about her being "difficult" on set originated. Director Kevin Smith later publicly described working with her as causing "crisis and trauma," suggesting that her perfectionism and unwillingness to compromise created production friction.

Whether that's fair criticism or gendered double standards applied to a woman who demanded the same control male actors received, we'll never fully know. What we can see is the result: Linda Fiorentino anchoring a religious comedy that could've been insufferable, making us care about a woman whose destiny is to prevent angels from destroying existence. That's not easy work. That's acting.

3. Men in Black (1997)

Director: Barry Sonnenfeld

Genres: Science Fiction, Action, Comedy

Main Cast: Tommy Lee Jones, Will Smith, Linda Fiorentino, Vincent D'Onofrio, Rip Torn, Tony Shalhoub

At first glance, ranking Linda Fiorentino's performance in Men in Black—the $589 million global blockbuster that made her more famous than everything else combined—at number three might seem perverse. Surely her most commercially successful film, the one that positioned her alongside Will Smith and Tommy Lee Jones in a cultural phenomenon, deserves top honours?

But remember: this is a ranking of her performances, not the quality of the films or their commercial impact. And while Men in Black is a superbly crafted summer blockbuster, Fiorentino is fundamentally playing a supporting role in a buddy comedy about her male co-stars. She's not the focus. She's not driving the narrative. She's the capable, intelligent woman who gets inducted into the organisation in the third act, setting up her return for a sequel that never used her.

That said, what Linda Fiorentino accomplishes within those constraints is remarkable.

As Dr. Laurel Weaver, a New York City medical examiner who stumbles into the Men in Black organisation's alien-policing operations, she's playing the audience surrogate—the rational, scientific mind confronting impossible phenomena. It's an archetype that often gets reduced to screaming, fainting, or providing romantic interest. Fiorentino does none of those things.

Watch her first encounter with an alien autopsy. Where a lesser actress would signal horror or disbelief, Fiorentino plays it as professional curiosity tinged with dry humour. When she's later recruited to become Agent L, she doesn't resist or require convincing—she makes the rational calculation that the job is more interesting than her current life. There's no romantic subplot with Agent J (Will Smith), no damsel-in-distress sequences. She's simply competent, funny, and equal to the men around her.

Director Barry Sonnenfeld understood what he had. Fresh off The Last Seduction and Jade, Linda Fiorentino brought instant credibility to a role that could've been an afterthought. When she deadpans responses to Will Smith's wisecracks or analyses alien biology with the same detachment she'd brought to corpses, she's grounding the film's more absurd elements. She's the bridge between the sci-fi premise and the audience's reality.

This ranks at number three because within the limited scope of what the role offers, Fiorentino is perfect. She's playing intelligence, competence, and unflappable cool—qualities that defined her best work. The tragedy is that Men in Black II replaced her with Rosario Dawson in a completely different role, denying us the chance to see Fiorentino fully unleashed as an equal partner to Jones and Smith in sequel adventures.

She reportedly turned down Men in Black II due to creative differences, specifically around how her character would be utilised. Given how the franchise evolved—doubling down on Smith's comedic energy while sidelining everyone else—she probably made the right call. But it's hard not to wonder what could've been if Hollywood had actually built a blockbuster franchise around Linda Fiorentino's particular brand of intelligence and danger.

2. Jade (1995)

Director: William Friedkin

Genres: Thriller, Crime, Drama, Mystery

Main Cast: David Caruso, Linda Fiorentino, Chazz Palminteri, Richard Crenna, Michael Biehn

Jade was savaged on release—an 18% Rotten Tomatoes score, box office disappointment, dismissed as a failed Basic Instinct knockoff trading on Joe Eszterhas' name and gratuitous sexuality. Critics accused it of incoherence, of prioritising exploitation over psychology, of wasting William Friedkin's considerable directorial talents on trashy material.

Twenty-nine years later, it's due for serious reappraisal.

This is William Friedkin—the director of The French Connection and The Exorcist—working in the erotic thriller genre at its commercial peak. He's not making exploitation. He's making a deliberately operatic, visually excessive psychological thriller about desire, corruption, and the impossibility of knowing another person. That infamous Chinatown car chase isn't gratuitous nostalgia; it's Friedkin demonstrating that the same kinetic energy he brought to The French Connection can be weaponised for pure aesthetic pleasure. The convoluted plot isn't incoherent; it's Friedkin and Eszterhas exploring how sexual obsession distorts perception and narrative truth.

And at the centre of it all is Linda Fiorentino doing career-best work that was completely overlooked because critics had already decided the film was beneath them.

As Trina Gavin, a psychologist whose secret life as the high-end escort "Jade" intersects with a murder investigation led by her ex-lover (David Caruso), Fiorentino is playing a woman whose sexuality has been simultaneously her power and her cage. Watch the interrogation scene where Caruso confronts her about her double life. Fiorentino doesn't play seduction or victimhood—she plays cold, controlled fury. Trina has carved out private space for her desires, separate from her marriage to a powerful attorney (Chazz Palminteri), and she's enraged that men keep trying to define, possess, or judge her for it.

What makes the performance extraordinary is Fiorentino's refusal to apologise for Trina or explain her. She doesn't give us backstory or trauma to justify why a successful psychologist would work as an escort. She simply plays a woman who wants what she wants, who's navigated the hypocrisies of male desire her entire life, and who's learned to use sexuality as both armour and weapon. When she coldly manipulates men, when she compartmentalises her marriage from her other life, when she ultimately confronts the consequences of inhabiting both worlds, Fiorentino finds psychological truth that the screenplay only hints at.

This is degree-of-difficulty work. Coming immediately after The Last Seduction, where she played a sociopathic femme fatale who destroys men without consequence, Jade gives her the inverse: a woman whose sexuality becomes the weapon used against her, whose double life makes her vulnerable to male violence and institutional power. Watching them back-to-back, you see Fiorentino exploring both sides of the archetype—empowered and destroyed, hunter and prey, always intelligent, never reduced to type.

Friedkin shoots her like a Hitchcock blonde—ice-cold beauty masking volcanic interior life. The film's visual excess, its operatic score, its willingness to push scenes past realism into heightened psychological space, all support what Fiorentino is doing. This isn't Basic Instinct's winking camp. It's a legitimate character study about female desire and the impossibility of authentic selfhood under male surveillance, wrapped in a murder mystery.

Critics dismissed it because they expected trash and refused to look deeper. Audiences stayed away because the marketing promised Basic Instinct but delivered something stranger and more ambiguous. But as Friedkin's reputation has been reassessed—particularly his willingness to work in disreputable genres and find art within them—Jade deserves to be seen as a serious, albeit flawed, entry in his filmography.

And Linda Fiorentino deserves recognition for giving Trina Gavin the complexity and dignity that contemporary critics refused to see. This ranks at number two because she's doing her best dramatic work, playing a woman who's neither victim nor villain but something far more interesting: a person trying to survive within systems designed to destroy women who refuse to perform conventional morality.

Roger Ebert, even in his lukewarm review, recognised it: "David Caruso and Linda Fiorentino are both very entertaining." That's critical code for "the performances are far better than the film's reputation suggests." He was right.

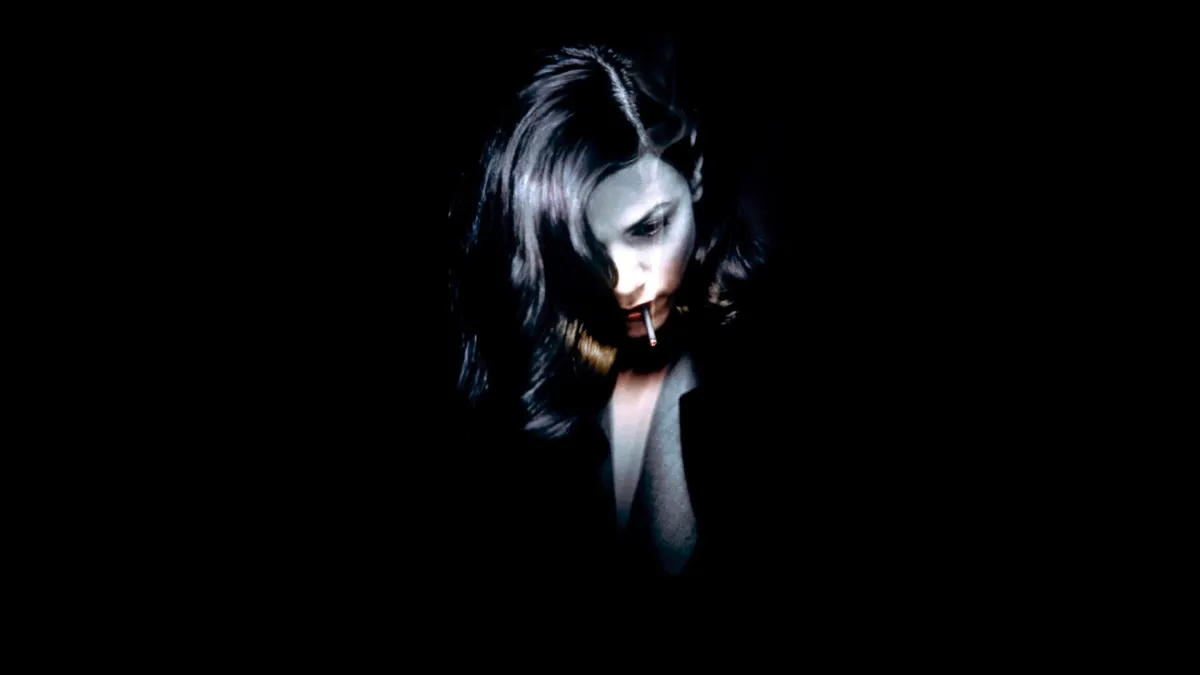

1. The Last Seduction (1994)

Director: John Dahl

Genres: Thriller, Crime, Drama, Romance

Main Cast: Linda Fiorentino, Peter Berg, Bill Pullman, J.T. Walsh, Bill Nunn

This isn't just Linda Fiorentino's best performance. It's one of the greatest performances in 90s independent cinema, period.

As Bridget Gregory—telemarketer, thief, seductress, murderer, and the most ruthless femme fatale committed to film since Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity—Fiorentino doesn't just inhabit the character. She weaponises every tool at her disposal: her voice (that distinctive husky delivery), her body (moving through frames with predatory confidence), her intelligence (always three steps ahead of every man), and her absolute refusal to apologise for any of it.

The plot is neo-noir perfection. After double-crossing her husband (Bill Pullman) in a drug deal, Bridget flees to a small town, adopts a new identity, and seduces a local man (Peter Berg) into helping her cover her tracks—and potentially commit murder. But plot summary doesn't capture what makes Fiorentino's performance transcendent.

It's the absolute control. In scene after scene, Bridget dominates every interaction. When she walks into a bar and propositions Berg's character with crude directness, she's the one pursuing, the one controlling the terms. When she manipulates him into believing she's in danger, she modulates her performance—becoming vulnerable, scared, dependent—while Fiorentino lets the audience see the calculation behind it. We're watching a master class in manipulation, and the horror is how effortless she makes it look.

Director John Dahl understood he'd found something special. He lets the camera linger on Fiorentino's face, trusting her to reveal Bridget's intelligence and contempt without dialogue. He gives her long scenes where she simply talks—long monologues about desire, about the stupidity of the men around her, about her absolute unwillingness to be constrained—and Fiorentino makes them riveting.

The performance earned her five major awards, including the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress and the Independent Spirit Award for Best Female Lead. She was nominated for a BAFTA. She should have been nominated for an Academy Award, but because The Last Seduction premiered on HBO before its theatrical run, she was deemed ineligible—a rule that sparked immediate controversy and was later changed.

That Oscar snub might be the only reason The Last Seduction isn't more widely recognised as one of the decade's essential films. But within film noir circles, among critics who track independent cinema, among anyone who cares about performance craft, Linda Fiorentino's Bridget Gregory is legendary.

Here's what makes it remarkable: Bridget is completely unsympathetic. She uses sex as manipulation. She destroys lives without hesitation. She's a sociopath operating in a genre that traditionally punishes transgressive women. Classic noir would have her dead or imprisoned by the final reel, morality restored.

The Last Seduction lets her win. And Fiorentino plays that victory without triumph, without vindication—just cold satisfaction, as if the outcome was never in doubt. The final shot, Bridget driving away having successfully framed her husband for murder, is chilling precisely because Fiorentino doesn't play it as "getting away with it." She plays it as Tuesday. This is simply what Bridget does. This is who she is.

It's a high-wire act of performance. Make Bridget too likeable and you lose the horror. Make her too monstrous and you lose the audience. Fiorentino finds the precise balance where we're simultaneously repelled and fascinated, where we recognise the manipulation but can't look away. She makes Bridget's amorality feel almost rational—the logical endpoint of being a woman who's refused to perform vulnerability or moral constraint.

The comparisons to Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity are inevitable, but they're also revealing. Stanwyck's Phyllis Dietrichson is also a murderous seductress, but she operates through traditional femininity—she uses the language of victimhood and desire that men expect. Bridget Gregory doesn't bother. She tells men exactly what she wants, mocks their weakness, and still gets them to do her bidding. That's the update. That's what Fiorentino brings that couldn't have existed in 1944.

After The Last Seduction, Linda Fiorentino should have become a major star. She should have had her pick of complex, challenging roles. She should have been first choice for every psychological thriller, every noir remake, every project requiring intelligence and danger.

Instead, she got Jade, Men in Black, and whispers about being difficult to work with. Within five years, her leading roles had dried up. Within fifteen years, she'd retired from acting completely, her final credit a 2009 direct-to-video comedy-drama that virtually no one saw.

But we'll always have Bridget Gregory. We'll always have that bar scene, that final drive, that perfect embodiment of female amorality that Hollywood has never quite figured out how to package or profit from. We'll always have proof that Linda Fiorentino, for one transcendent performance, redefined what a woman could be in film noir.

That's why The Last Seduction ranks number one. Not just because it's her best performance—though it is. But because it's the performance that proves what she could have been, what Hollywood lost when it couldn't figure out what to do with an actress this intelligent, this dangerous, this uncompromising.

The tragedy isn't that Linda Fiorentino walked away from acting. The tragedy is that the industry walked away from her first.