Everyone says it was a crime.

Ordinary People beating Raging Bull at the 1981 Oscars. Suburban therapy sessions triumphing over Scorsese's masterpiece. A first-time director defeating the greatest living filmmaker.

The Academy got it wrong. Again.

Except they didn't.

What looks like Hollywood choosing safety over genius is actually the story of how a perfectly crafted film arrived at exactly the right cultural moment—while its competition arrived at exactly the wrong one.

The real question isn't "Why did Ordinary People win?"

It's "Why does everyone think it shouldn't have?"

The Night Everything Changed

31st March 1981. The 53rd Academy Awards, postponed one day following the assassination attempt on President Reagan.

The nominees for Best Picture:

- Ordinary People

- Raging Bull

- The Elephant Man

- Coal Miner's Daughter

- Tess

Here's what people forget: The Shining received exactly zero Oscar nominations. Kubrick's masterpiece was ignored entirely.

So when people ask why Ordinary People beat The Shining, they're asking the wrong question.

The real contest was Ordinary People versus Raging Bull.

Why Hollywood Was Exhausted

November 1980. Heaven's Gate premieres.

Budget ballooned from $11 million to $44 million. Box office: $3.5 million. United Artists effectively bankrupt.

This wasn't an isolated incident. It was the death knell of an entire era.

After The Godfather and Easy Rider became massive hits, studios gave young auteur directors unprecedented creative control and unlimited budgets. The "New Hollywood" era. Directors as gods.

Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now (1979) started at $12 million, ended at $31 million. Production chaos. Typhoons. Heart attacks. Nervous breakdowns. Nearly bankrupted him personally.

Michael Cimino's The Deer Hunter (1978) won Best Picture, earned him unlimited power. Then Heaven's Gate destroyed United Artists entirely.

Cocaine was rampant in 1970s Hollywood—directors, actors, executives. It fuelled the "anything goes" mentality, the lack of financial oversight, the belief that artistic vision justified any excess.

By 1981, studios wanted fiscal responsibility and controlled filmmaking.

Ordinary People—a modest $6.2 million film, tightly controlled, professionally executed—represented Hollywood saying: "Enough."

But that's not why it won.

You may like...

The Raging Bull Problem

Raging Bull is a masterpiece. Moody black and white. Visceral, complex, forbidding. It confuses, disorients, causes the stomach to churn.

Most Academy voters watch entries once.

Raging Bull received decidedly mixed reactions from critics. Box office failure: $23 million against an $18 million production budget. Too challenging. Too dark. Too much.

Compare that to Ordinary People:

- $90 million gross on $6.2 million budget

- CinemaScore audiences: rare "A+"

- Critical consensus: masterful restraint

One film punished viewers. The other trusted them.

What Ordinary People Actually Did

Robert Redford had zero directing experience.

Not quite.

He'd spent fifteen years as an actor studying Alan Pakula, George Roy Hill, Sydney Pollack. Every close-up in All the President's Men. Every editing choice in The Sting. Every frame of Three Days of the Condor.

Then he produced Downhill Racer (1969), essentially directing without the title.

By 1980, Redford had attended the world's most exclusive film school. He chose material perfectly suited to what he'd learned.

Redford even eludes to this fact in his Best Director speech at the Oscars...

The Technical Mastery Nobody Discusses

Watch that phone sequence in All the President's Men. Director Alan Pakula keeps the camera intensely still. No frenetic coverage. Just trust in Redford's ability to make thinking look dramatic.

Four years later, Redford remembered. When Timothy Hutton sits opposite Judd Hirsch in therapy sessions, the camera barely moves. Static shots. Long takes. Let the actors breathe.

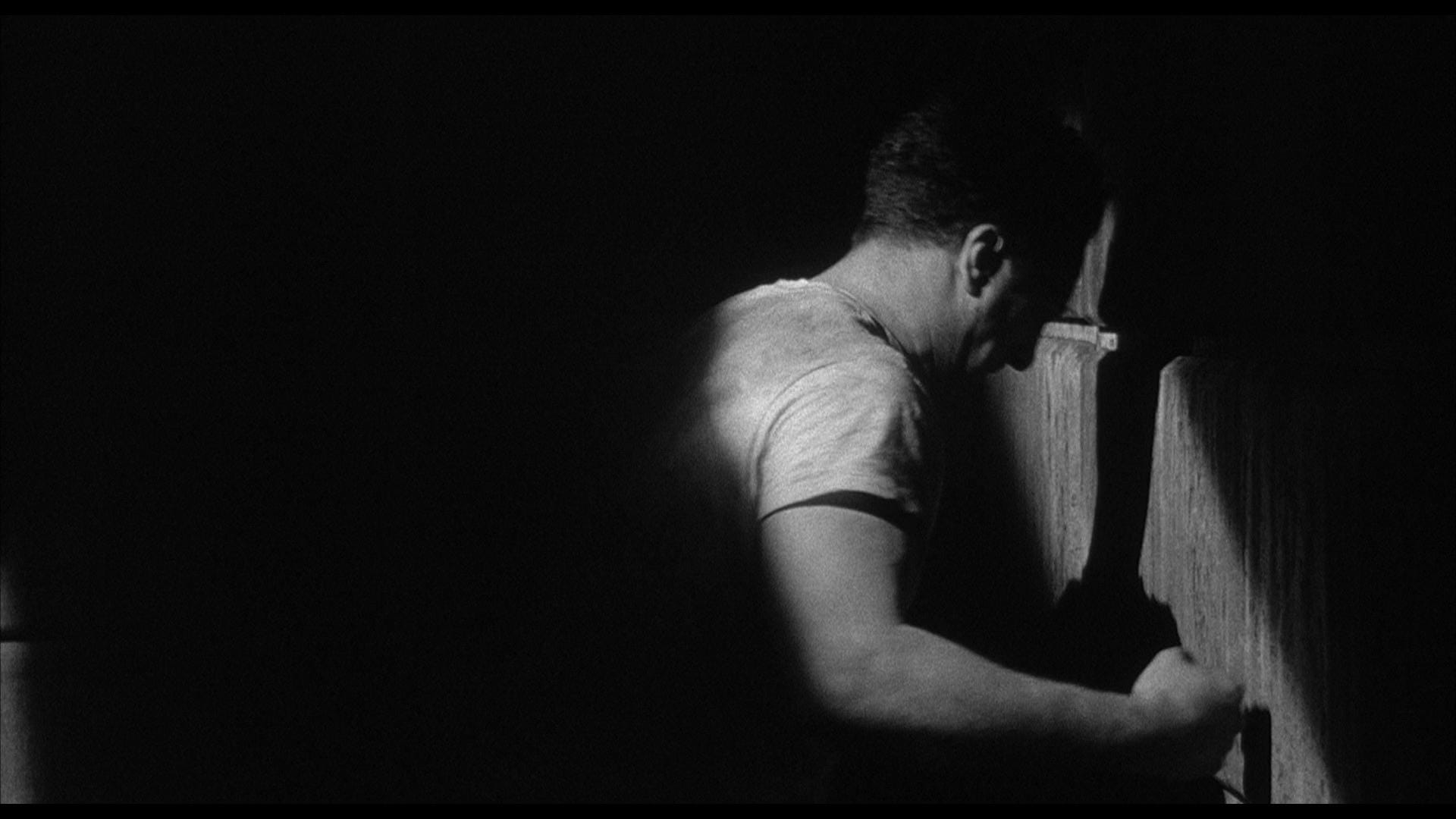

Cinematographer John Bailey brought Gordon Willis's philosophy—"The Prince of Darkness" who revolutionised shadow and underexposed film. The therapy room's low-key lighting creates increasing intimacy with each session. Darkness creating emotional meaning.

Editor Jeff Kanew cuts between Dr. Berger's office and Conrad's memories with surgical precision. The film breathes slowly. When it needs to punch? It punches.

The editing is invisible. Which is exactly the point.

The Perfect Gift For Film Lovers - Any purchase goes towards keeping our site alive.

What It Did for Film

Before Ordinary People, psychiatrists were shown negatively as "shrinks." Judd Hirsch's Dr. Berger—warm, present, genuinely helpful—became the template for positive therapy representation. The psychiatric community praised it as one of the rare times their profession appeared accurately.

The film arrived at a cultural watershed. PTSD was formulated by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980. Adolescent suicide rates were climbing. Conrad's journey became painfully relatable.

The previous Best Picture winner? Kramer vs. Kramer—family coping with divorce. Ordinary People continued the trend: mainstream films addressing the dysfunctional American family.

Revolutionary subject matter handled with masterful technique.

The Casting Genius

Beth Jarrett. The heart of the piece.

Redford always wanted Mary Tyler Moore, yet "auditioned every actress in Hollywood" before returning to her. The casting caused significant stir—Moore was welded into public consciousness as an icon of chirpy respectability.

Her transformation here is staggering. She scaffolds gaping emptiness with a persona of perfection.

Donald Sutherland and Mary Tyler Moore with Timothy Hutton in Ordinary People

Donald Sutherland's criminally overlooked performance as Calvin deserved nomination. Watch him talk about his marriage at the psychiatrist's office, eyes constantly looking away as he says how much he loves her.

Restraint creating devastating truth.

Timothy Hutton at 20 became the youngest male Oscar winner ever. He underwent intense psychological preparation with actual therapists to capture Conrad's emotional struggles genuinely.

This wasn't accidental. Redford learned from Sydney Pollack, whom he met on his first acting job in War Hunt (1962). Seven films together. A decade-long masterclass.

Pollack's visual grammar: the camera serves the actors. Medium close-ups, two-shots showing relationships, minimal coverage.

Watch the breakfast table scenes: two-shots of Calvin and Conrad. Beth isolated in singles. The camera tells you who's connected and who's adrift.

Why Raging Bull Felt Wrong in 1981

Martin Scorsese made a punishing masterpiece about toxic masculinity and self-destruction. Absolutely exhausting.

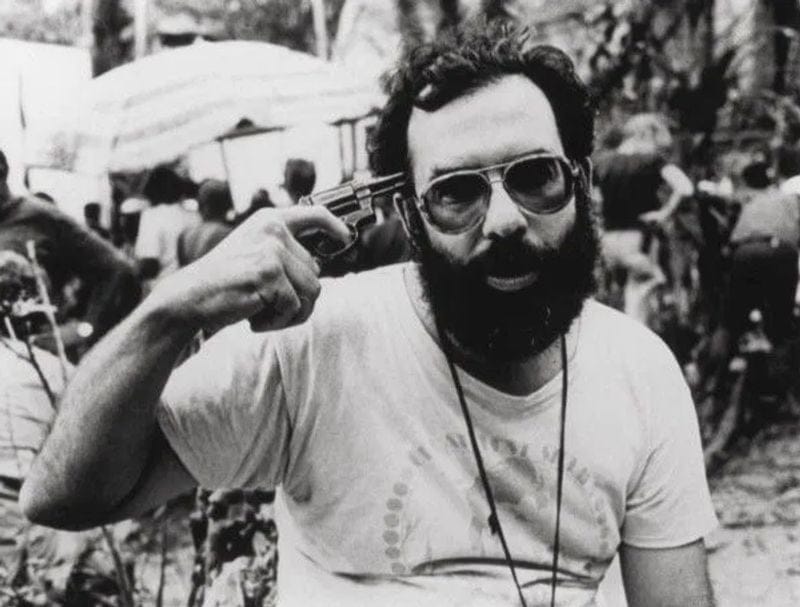

Martin Scorsese's Raging Bull

Ordinary People made a different choice. It examined suburban facade. It showed therapy working. It suggested healing was possible.

Roger Ebert gave it four stars, praising how the setting is seen with an understated matter-of-factness. There are no cheap shots against suburban lifestyles.

It’s not often we get characters who face those kinds of challenges on the screen, nor directors who seek them out. “Ordinary People” is an intelligent, perceptive, and deeply moving film.

This mattered in 1981. The industry wanted hope. Audiences wanted connection. Critics wanted craft without ego.

Ordinary People delivered all three.

The Four Wins

Best Picture. Best Director. Best Adapted Screenplay. Best Supporting Actor.

Not because Raging Bull lost.

Because Ordinary People won.

The title sequence tells you everything. No score. Just white letters on black background gradually lightening into blue autumn sky. Colour indicating the trajectory from dark void into understanding.

Setting begins in autumn. Climaxes around Christmas. Pachelbel's Canon in choir scenes—played at both weddings and funerals, echoing the film's equal measures of emotional progress and cessation.

Every choice deliberate. Every frame intentional.

What Happened After

Redford waited eight years before directing again.

The Milagro Beanfield War (1988) tackled a subject nobody else in Hollywood would touch: Latino land rights, environmental exploitation, corporate greed in small-town New Mexico. Mixed magical realism with social justice. Featured a largely Latino cast.

Critics were mixed. Audiences weren't sure what to make of it. But Redford took on material that mattered, exactly as he had with Ordinary People—a film about suburban families confronting mental health and suicide when nobody else would.

Restraint in technique doesn't mean restraint in subject matter. Redford never played it safe thematically.

A River Runs Through It (1992) marked a return to form. Philippe Rousselot's Oscar-winning cinematography. Trust in silence, spaces, emotional understatement.

Quiz Show (1994) cemented it. Four Oscar nominations including Best Picture and Director. David Ansen wrote: "Robert Redford may have become a more complacent movie star in the last decade, but he's a more daring and accomplished filmmaker."

The Horse Whisperer (1998) was Redford's love letter to Montana, to nature, to healing. He directed, produced, and starred in it—a deeply personal project about trauma, family, and the redemptive power of the natural world. Critics were mixed, but the film captured something essential about Redford himself: his belief in patience, in quiet transformation, in letting landscapes do emotional work.

The pattern revealed itself across his best work:

Trust in Silence. The Christmas photo scene in Ordinary People. Montana landscapes in River and Horse Whisperer. Moral conflict in glances in Quiz Show.

No Emotional Manipulation. Minimal music. Let performances breathe.

Intimacy Over Spectacle. Personal stories trump epic scope.

Commitment to Subjects That Matter. Mental health. Environmental justice. Healing through nature. Corporate corruption.

The Vindication

Film schools still study Ordinary People. Medical schools use it to teach family systems. The psychiatric community still references it.

Meanwhile, Raging Bull ranks on every "greatest films" list.

Both films won. Just in different ways.

Redford proved restraint isn't weakness—it's mastery.

Not a fluke. Fifteen years in the making.

The Real Answer

Why did Ordinary People deserve to beat Raging Bull?

Because in 1981, Hollywood needed to remember that technical mastery doesn't require punishment. That quiet devastation can be more powerful than visceral violence. That therapy working is more revolutionary than showing it fail.

Raging Bull is a masterpiece of cinematic brutality.

Ordinary People is a masterpiece of cinematic restraint.

The Academy didn't choose wrong. They chose differently.

And history has been kind to both.

Time to stop calling it a robbery and start calling it what it was: two different films, both brilliant, one more suited to its moment.

The real crime? Pretending Ordinary People didn't earn what it won.

Comments ()