In 1998, a British filmmaker delivered the film that changed cinema forever.

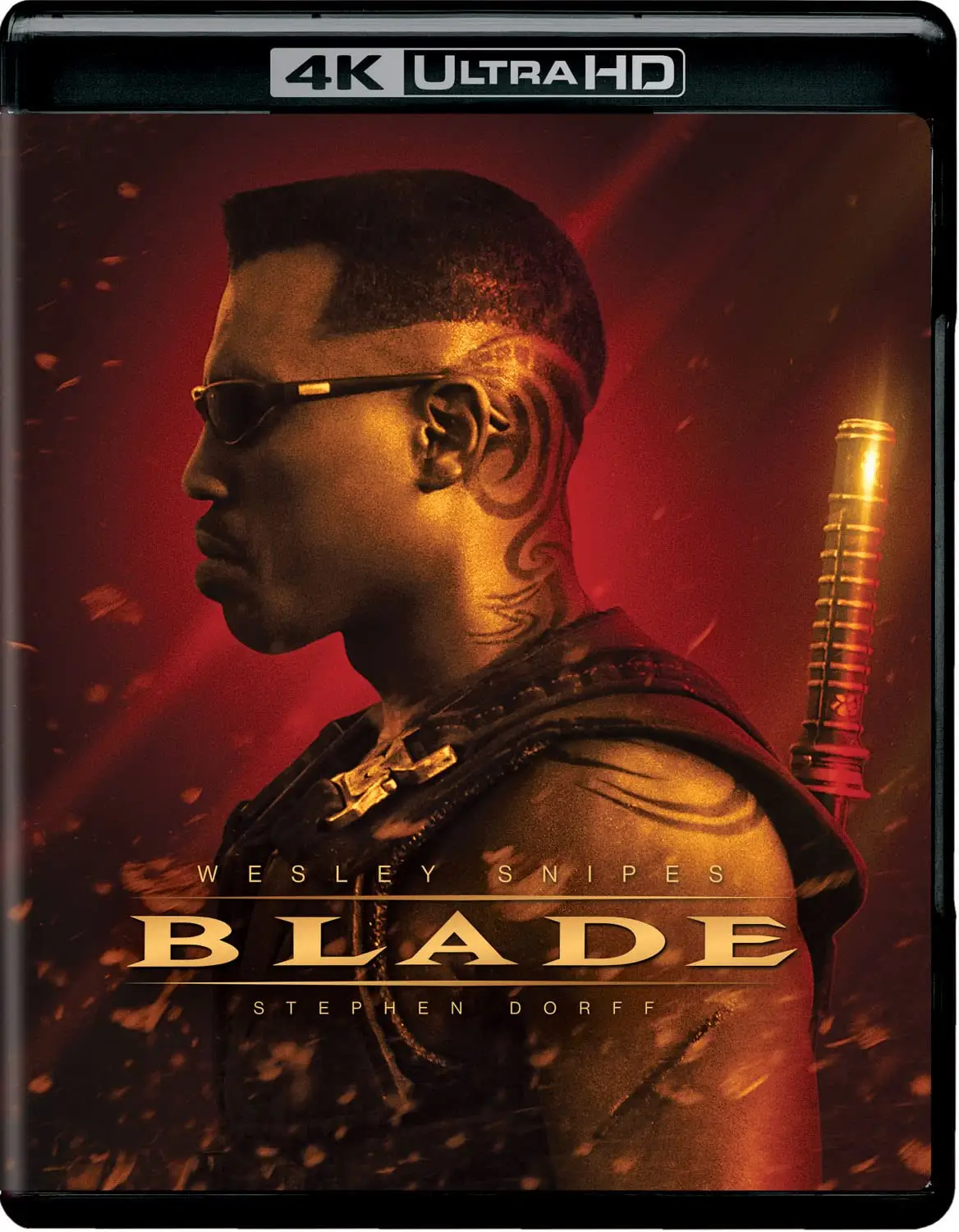

Blade wasn't just another comic book adaptation—it was the prototype for every superhero blockbuster that followed. Stylish, violent, unapologetically R-rated, it proved superhero films could print money and matter culturally. This was two years before X-Men, four years before Spider-Man, a decade before Iron Man suited up.

The director was Stephen Norrington.

Hollywood wanted everything he had to offer. Or so it seemed. As Norrington clarifies, the studios wanted his results—but they weren't ready for his methods. "Hollywood most certainly did not want what I had to offer after Blade," he notes.

Five years later, he'd never direct a studio film again.

For years, the industry narrative has been that Norrington "vanished" after a catastrophic failure, a "broken" man who vowed never to direct again. The truth is far more interesting.

Preamble: When the Subject Calls Back

When the email came in, I was jointly terrified and completely awe-struck. I'd spent a week researching a man who famously went toe-to-toe with Sean Connery, who'd told legendary stories about inviting people to punch him in the face. I steadied myself, expecting a sharp lashing.

Instead, Norrington spoke so candidly and personably that it took me by surprise.

Continued...

In four years of writing, only one other person had ever contacted me to correct an article. Now here was a major Hollywood director taking the time to set the record straight. The fascination wasn't just professional; it was deeply personal. I'd genuinely enjoyed both Blade and LoEG. And Death Machine? If Brad Dourif chooses a film to be in, I'm all the way in. I told him as much, admitting I'd never read Moore's graphic novel, so I'd watched the film through a less critical lens than many who'd savaged the adaptation. This, he clarified, was precisely the point—the film was never meant to be a faithful adaptation.

What struck me most was this: I hadn't got things "wrong" so much as inaccurate, limited by the mythology the internet had built around him. And here he was, willing to dismantle that mythology piece by piece. I'm grateful—both for myself and for him—that we can now set the record straight and remove the mythology attached to his name (though he finds the whole thing rather humorous).

Straight away, I could tell the internet had him wrong. Reading his so-called "rambles"—which weren't rambles at all, but thoughtful, specific corrections—I found myself deeply respecting him. An uncompromising creative. A man who forged his own destiny. Someone with an undeniable love for film and zero tolerance for the mythology that's built up around his career.

The article below has been fully updated with his direct, on-the-record remarks. This isn't the story of a broken man who vanished. It's a story of principle over profit.

THEN: An Up And Coming Director in Hollywood

Norrington started in the trenches. Practical effects work—sculpting creatures for Aliens, building models for Return to Oz and Split Second throughout the '80s and early '90s. His directorial debut, Death Machine, arrived in 1994: a grimy, low-budget techno-horror flick that most people ignored.

But Blade was different.

It grossed $131 million worldwide on a $45 million budget. Wesley Snipes became a bonafide action star. Critics praised its kinetic energy and gothic aesthetic. Norrington could have written his own ticket.

Hollywood threw a mountain of projects his way: not just franchise sequels like Blade II, but also films like From Dusk Till Dawn, a Jean-Claude Van Damme vehicle (Maximum Risk), and The Mutant Chronicles. He also developed Ghost Rider for four years and Shang-Chi for two.

He turned most of them down.

Industry lore paints him as elusive, flighty even. The reality was far more calculated. Norrington had seen how studios locked down young talent with three-picture deals—enticing on paper, potentially catastrophic in practice. If your first film tanked, you were contractually obligated to direct whatever the studio assigned next. He wanted none of it.

"I told my agent that I'd only do a 1-picture deal for Blade," Norrington says. "The studio was simultaneously offended and nonplussed—I think they figured I was mentally ill."

They made the deal anyway. Looking back, Norrington recognises this resistance as an early warning sign: "I wasn't temperamentally suited to being a Hollywood filmmaker."

Fancy this 4k Ultra HD copy of Blade? Your purchase helps keep our site alive.

The Passion Project

Instead of a blockbuster sequel, Norrington chose to make The Last Minute in 2001—a dark, urban thriller focusing on the catastrophic, public downfall of Billy Byrne, a young, intensely self-obsessed celebrity on the cusp of becoming the Next Big Thing. After his moment of glory is ruined, he loses everything and is forced to descend into the perilous underbelly of London, navigating a world populated by criminals, murderers, and unscrupulous "talent agents." It's a stylized look at fame, failure, and the ultimate price of ambition.

Reports often claim he self-financed the film and drained his bank account. Not true. Norrington corrects the record: it was wholly financed by Palm Pictures. He did personally put £70k into VFX when the budget ran over, but it didn't leave him in a precarious position.

It remains his favourite of his four films. A "UK grime-fable about the perils of ego."

I've seen it. It has these urban-gothic vibes—a stylised "cult" pic that feels deeply personal. You can see Norrington's visual DNA throughout: the atmosphere, the grit, the refusal to play safe. Watching it, you can trace a direct line to what he'd attempt with LoEG—that same commitment to building a complete world with its own internal logic and aesthetic.

Crucially, he didn't rush into his next project out of financial desperation. "I did not need a paycheck," Norrington asserts—he'd made good money from Blade. He even had a deal with James Cameron to develop a Space Alien movie called Brother Termite, and whilst waiting for that to greenlight, he post-produced The Last Minute at Cameron's Santa Monica facility.

Neither Brother Termite nor Ghost Rider got greenlit. So he took the LoEG job.

Behind the vanishing acts: Explore our full database of archival records and investigative profiles.

The Definitive Cut: Revisiting Death Machine

Norrington's drive for creative control isn't limited to his current work. He's recently returned to his debut film, Death Machine, to fix what he saw as the original release's flaws.

The 2024 Director's Cut "can be considered the definitive cut, director approved," Norrington states. He personally produced the new version, re-editing virtually every scene and creating new VFX to speed up the pace. The goal? "Remove a ton of overwrought bathos and emphasise fun stuff."

Working with composer Paul Rabjohns, he completely overhauled the soundtrack—creating a new 7.1 audio mix with new music, fixing the "tonal issues with the original music" and replacing "overwrought cues with new music that is less abrasive, more cinematic."

It's a perfect demonstration of his uncompromising commitment to seeing his original creative vision realised. Even decades later, even on a film most people have forgotten, he's still fighting for what he believes the work should be.

I find this admirable. Here's a man who clearly had a creative vision for the film, felt he'd fallen short with the released version, and wanted to release the version he'd always intended. Not for money—there's no fortune in re-cutting a 1994 techno-horror film. For principle. For craft. Because the work matters more than the reception.

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen

When 20th Century Fox offered him The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (LoEG) in 2003, his acceptance wasn't about the money.

It was about the canvas.

"I signed onto LoEG because I thought it was a cool project that was actually going to get made," Norrington explains, citing the film's "potential for world building and an exhilarating lack of concern for boring realism." He was initially working from the "great Robinson script" (by writer James Robinson).

But he admits there was always a fundamental disconnect between the source material and the studio mandate. Whilst he admired Alan Moore's graphic novel as a "dark, cynical and provocative adult work," he recognised that the movie was never going to be that.

"The movie... was always going to be a PG-13 kid-friendly romp propped up by a well-loved movie star."

That star was Sean Connery, who signed on for $17 million. But there was another problem brewing beneath the surface—one that would prove more damaging than any creative disagreement.

In Conversation with Stephen Norrington

The Blade director opens up about his creative process, Hollywood politics, and what he's working on now

The Freedom That Blade Had (And LoEG Didn't)

On Blade, Norrington had enjoyed remarkable directorial freedom. Wesley Snipes supported his choices. New Line allowed him to work the budget cleverly with the line producer. Most crucially, Norrington had massive input into Blade's music scheme and how the edit, music, and sound interlocked.

This matters more than you might think.

"Blade is a significantly more effective film than LoEG because the music and picture are so tightly interlocked," Norrington explains.

Fox didn't allow him the same input on LoEG. "They regarded composers as at least as important as directors on movies that size and the composer was uninterested in taking notes from me," he says. The music ended up "pretty generic" and didn't take the picture edit into account.

The budgetary approach was different too. LoEG wasn't underfunded—it had $81 million—but Fox's producorial middle management were "always keen to spend top dollar, to cover their arses I guess." There was little openness to being ingenious and cost-effective. On Blade, clever solutions were encouraged. On LoEG, they were discouraged.

These structural problems would collide with a natural disaster to create the perfect storm.

The Flood, The Fury, and The Fallout

Production began in Prague in 2002. The troubles started almost immediately.

Historic floods hit Prague, causing millions in damage. But Norrington insists the flood itself wasn't the catastrophe—the studio's reaction was.

"The studio didn't want to give us money to cover the delay caused by the floods," Norrington reveals. Instead, "they wanted us to find funds from within the existing budget which meant cutting things we'd already committed to."

Think about that for a moment. They'd partially filmed scenes—committed resources, planned sequences, built sets. Now the studio wanted them abandoned to pay for a weather delay. Not because the scenes were bad. Because accountants needed somewhere to find the money.

This sparked the conflict. Norrington refused to abandon scenes he felt were necessary for the story. The studio demanded he cut them.

"I figured it was my job to stand up for the movie," he says. "The studio figured it was their job to come in under budget."

These compromises took their toll. Norrington believes the film suffered because of how they were forced to cut crucial character moments and large-scale scenes, like a powerful sequence involving "all world leaders" in the background. Reflecting on the final product, he regrets not being able to focus on atmospheric touches: if he could do it over, he'd look at changing the soundtrack and adding in more establishing shots of characters or scenery.

His rigidity on set extended to his relationship with Connery. Norrington admits he was a "greenhorn director who always talked back" and "didn't give a hoot about his legendary status."

"I was always more impressed by Rob Bottin than by movie stars."

"I was surprised to discover how steely/rigid/inflexible I could be in my defence of the movie's content, viewing it in hindsight as a clue that I wasn't temperamentally suited to being a Hollywood filmmaker."

But his rigidity wasn't blind stubbornness. Norrington estimates "about twenty percent of things I fought for and won are crap, and about twenty percent of studio notes I resisted but was forced to do are great." He also acknowledges the other side:

"It's not reasonable for me to expect that film financiers should give me their money without them being involved in the process—if I was financing a movie I'd want to be involved with how my money was being spent."

The problem was finding a system that worked for both parties. LoEG proved it didn't exist—at least not for him.

And the infamous fight?

The Human Moments

The set wasn't all warfare.

Norrington has genuinely warm memories of cinematographer Dan Laustsen and First Assistant Camera Julian Bucknell. "We laughed a lot and they didn't hesitate to call me on my shit," he recalls. There were good days, moments of genuine collaboration and creative flow.

But anonymous crew members fed a different story to the press—tales of an indecisive director setting up scenes multiple ways, shooting material that would never make the cut, burning hours. Norrington rejects this entirely:

"I did know exactly what I wanted: I wanted a lot of coverage because, er, you need a lot of coverage to edit a movie freely."

It's the logic of someone who understands post-production. More angles, more options, more freedom in the edit. What looked like indecision was actually insurance.

Connery later famously told The Times to "check the asylum" when asked about his director. Norrington takes it in stride:

"Honestly, 'Have you checked the local asylum?' is a classic retort... perfectly timed and completely off the cuff," he says. "Connery was always extremely sharp and witty."

What LoEG Actually Achieved

Despite the production difficulties, Norrington defends what made it to screen.

He points to what they accomplished for $81 million (including Connery's $17 million salary and all the studio's internal costs) as "evidence that LoEG was an unusually tight ship with an unusually clear vision."

The film's visual style, he notes, is "exceptional"—with its "gleeful embrace" of unrealistic aesthetics. Norrington quotes William Goldman: "Give the reader what they want, just not the way they expect it." He argues that whilst Fox tried to do precisely that, "vocal audience members would have preferred that we 'give them what they want exactly how they expected it.'"

It's this ambitious stylistic vision—the exuberant world-building, the refusal to be bound by "boring realism"—that Norrington remains proud of. The compromises he regrets weren't creative choices. They were the atmospheric character moments and large-scale sequences they were forced to abandon to cover a weather delay.

I enjoyed the film when I first saw it. Rewatching it for this article, what struck me most was the scenery—those dark English cobbled streets, the mist, the lighting. There's a texture to the world Norrington built that feels tangible in a way modern green-screen blockbusters rarely achieve. Was it exceptional? Perhaps not. But it was distinctive, enjoyable, and in recent years, the narrative around the film seems to be shifting more positive. Sometimes a film just needs time and distance from the production drama to be seen for what it actually is.

The Critical Massacre?

LoEG opened in July 2003 to withering reviews. The narrative was set: the film was a "creative disaster" and a box office bomb.

Except the numbers tell a different story.

Norrington points out that LoEG grossed approximately $179 million theatrically, plus another $84 million in home video revenue. "Totalling over $263 million," Norrington notes. "Which, I should point out, is a quarter-billion dollars."

The film was "solidly profitable."

Norrington himself offers a telling anecdote. He didn't attend his own film's premiere—he couldn't imagine anything "more inauthentic than glad-handing with people you recently had a horrible time with." Instead, he drove to Las Vegas and watched the red carpet shenanigans anonymously from the crowd outside the Venetian Hotel.

"It cracked me up watching Connery and the suits having to explain to reporters why the idiot director was not at the event," he recalls.

Then came the moment that crystallised everything. "I asked a person next to me what the premiere was for—he said 'It's that new Johnny Depp movie, Pirates of the Caribbean.'"

In that moment, Norrington knew how things were going to go down. The film was destined to be overshadowed—by Connery's retirement narrative, by the behind-the-scenes drama that leaked to the press, by opening the same summer as a Johnny Depp vehicle that would become a cultural phenomenon. The marketing failed to land. The controversy became the story. And once the "disaster" narrative takes hold, actual box office performance becomes secondary to the mythology.

The notion that Sean Connery retired because of this experience is also misleading. Norrington clarifies that Connery:

"had already decided to retire and took on the LoEG role because it nicely wrapped up his career." He was performing the part of the "old warhorse, one more adventure, hands the mantle to the new generation and dies."

The real disaster for Norrington wasn't the reviews or the box office. It was the realisation that he didn't want to work with financiers who insisted on being involved in the creative process.

The "Lost" Projects

Norrington didn't vanish immediately. He spent years developing authentic takes on major projects, but his uncompromising style proved incompatible with the studio system.

"What actually happened was I bailed on all the projects I was developing after LoEG was over - when I got back to LA I wrote a form letter to all producers involved with all those projects and bailed out on all of them."

Akira: Warner Bros. cancelled his Akira adaptation. Norrington clarifies that this cancellation was not due to the LoEG fallout, but because he "turned in a treatment that Warner Bros hated."

Clash of the Titans: He was replaced not for creative failure, but because he went on a pre-planned expedition to the South Pole instead of staying available for studio meetings. Let that sink in. "They'd been offended that I went on the trip... so they'd replaced me with [Louis] Leterrier." (which he stated probably worked out best for everyone.)

The Crow: He wrote four drafts, but walked away when the studio insisted he meet with Mark Wahlberg for the lead. "Wahlberg hated my entire concept but 'loved my work,'" Norrington recalls.

"I came to the conclusion... that my position wasn't tenable," he says. "Film financiers want to turn a profit—I want to do exactly what I want to do, damn the audience."

So, he left. Moved out of LA, lived in Berkeley for seven years, and spent a decade going to Burning Man.

Hollywood lost something when Norrington walked away. A unique, divisive director—yes—but one who'd already proven he could make them a fortune. They didn't want him, yet Blade launched an entire genre. Imagine what a big-budget film from Norrington could have been if he'd been truly unleashed and untethered. His Akira. His Clash of the Titans. His authentic take on The Crow. (It would have been a damn sight better than the last rubbish attempt that's for sure!)

We'll never know. And that feels like a loss, even if it was inevitable.

The Miniatures Tease and The Migrant

In 2018, Stephen Dorff—who played Deacon Frost in Blade—told Entertainment Weekly that Norrington was "making a movie at his house right now with miniatures, it's gonna take him like 10 years."

Not quite accurate, but close in spirit.

Norrington clarifies that Dorff was conflating three separate DIY projects. The current film, titled The Migrant, is a small sci-fi robot movie—feature length with a 7.1 soundtrack. It's a mix of live action, practical effects, and CG. He realised modern technology had advanced to the point where one could make a professional feature "basically single handed!"

He's in post-production now and estimates it will perhaps be finished within a year. It has certainly been "the best experience of my life," he notes.

And he's not stopping there. He's already ramping up his next project.

What I Learned

After exchanging emails with Stephen Norrington, one thing became clear: this is a man of extraordinary creative integrity.

He knows exactly what he wants. He wasn't prepared to diminish his morals or creative process to appease executives in a boardroom. He chose freedom over fortune, craft over compromise. When the system proved incompatible with his vision, he didn't break—he walked.

Was he perfect and an absolute charm to work with? No. (by his own admission he was a giant manbaby!😂)

I see a lot of myself in him, honestly (not so much the manbaby). That stubbornness to stay true to your vision even when it costs you. That willingness to be misunderstood rather than diluted. It's not always the smart choice financially, but it's the only choice that lets you sleep at night.

The internet built a mythology around his "disappearance"—a broken man, defeated by Hollywood, vanishing into obscurity. But reading his thoughtful corrections, understanding his choices through our correspondence... none of that rings true. This is someone who made deliberate decisions, paid the price, and has no regrets.

That's not defeat. That's integrity.

Where Is He Now? The Economics of Independence

Is he a "broken" man, hiding from the industry?

"I like the idea that LoEG broke me so fundamentally I could never work with studios again," Norrington muses. "It sounds a bit like Shelley Duvall in The Shining... but broken? Nah. Wised-up, more like."

In another world, Norrington directed Blade sequels or an early Avengers film. He'd be at Comic-Con panels. Have a Marvel Legends figure in his likeness. His candid response to that was "I didn't and don't want to." Instead, he works on his own dime, at his own pace, making exactly what he wants.

But how does a former blockbuster director sustain this lifestyle?

Norrington's current filmmaking model challenges everything Hollywood assumes about what it costs to make a film. The Migrant, his latest project, came in at roughly $50,000—a figure that includes durable equipment he'll reuse for years.

His ability to sustain this approach stems from strategic choices made during his studio years. He made good money from his blockbuster films and crucially, didn't spend it. Life is good, health insurance is covered, and freedom is absolute.

His production methodology would make studio accountants weep—or perhaps take notes. The camera he used cost $2,000; in side-by-side tests, the footage proved indistinguishable from a "professional" camera costing $45,000. His tripod came from Amazon for $30. A colleague's supposedly superior model? $1,600. He built his own crane arm from timber bought at Home Depot.

The real savings come from doing everything himself. He taught himself CGI using free software, eliminating companies that would charge hundreds of thousands. He records world-class sound on affordable equipment. He composes music using free programmes. He edits on a 13-year-old laptop.

"I learned practical effects when I was young by doing them," he explains. "More recently, CGI VFX by downloading free software and learning how to use it. Now VFX are a trivial operation in my pipeline. It's slower than how studios do it but 99.99% cheaper."

He doesn't pursue money-making in the traditional sense, accepting what he calls a "mild loss" as unavoidable depreciation for doing exactly what he wants. If The Migrant finds distribution and recoups its costs, that would suit him just fine. But it's not the point. The work itself is the reward.

His philosophy distills to three decisions: get into the business and make good money, get out and reduce life costs to minimal, make your own projects for micro budgets by learning every necessary trade yourself.

"Life is better when it's simpler. I tell people the two best decisions I made in my life were to get into the movie biz and get out of it. These days I add a third decision: make my own movies on my own dime at my house."

For Norrington, that simplicity has purchased something studios can't buy: absolute creative freedom.

Norrington referred to this sentence in the original article (He built the blueprint for the superhero era, then disappeared.) as "sounds like a pretty good mic drop to me." but for me, the real mic drop is the last sentence of this article.

Will The Migrant ever be released?

"No idea," says the man who launched the superhero era.

"Do I care much? Not really." (BOOM!)

What Happened To?

Check out these articles to see what happened to other big stars who faded from the spotlight: