The 1990s should be remembered as science fiction's golden decade. We got Terminator 2, The Matrix, Jurassic Park. But while those blockbusters hoovered up all the attention and box office receipts, some genuinely brilliant sci-fi films slipped through the cracks.

These aren't just forgotten curiosities. They're films that took risks, explored dark themes, and pushed boundaries when the studios wanted safe bets. Some bombed spectacularly. Others never got proper releases. A few built cult followings on late-night cable and VHS rentals.

Here are fifteen 90s sci-fi films that deserved far better than they got.

I Come in Peace (1990)

Directed by Craig R. Baxley

You probably know this one as Dark Angel if you caught it outside North America. Either way, you probably didn't catch it at all.

Dolph Lundgren plays a Houston cop tracking an alien drug dealer who's killing people to harvest endorphins. The premise sounds ridiculous because it absolutely is. But director Craig R. Baxley—a stuntman turned action maestro—delivers exactly what the concept promises: explosive, unpretentious action wrapped in neon-soaked 80s aesthetics that somehow landed in 1990.

The alien's weapon shoots lethal CDs. Yes, compact discs. It's gloriously stupid.

I Come in Peace bombed with just $5 million against its $7 million budget, largely because nobody knew what to call it or how to market "Dolph Lundgren versus a drug-dealing alien." But it's aged into a cult classic that understands its own absurdity without winking at the audience. Sometimes that's enough.

Until the End of the World (1991)

Directed by Wim Wenders

Wim Wenders' globe-trotting epic runs 158 minutes in its theatrical cut. The director's cut? Nearly five hours.

That should tell you everything about why this visionary film never found its audience. Until the End of the World follows Claire (Solveig Dommartin) as she pursues a mysterious man (William Hurt) across continents in 1999, just as a nuclear satellite threatens Earth. The film's second half shifts into something stranger: a device that records dreams, and the addictive consequences of watching them.

Wenders commissioned original music from U2, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, and others. The soundtrack alone is a time capsule of early 90s alternative rock meeting art-house ambition.

The problem? Audiences in 1991 weren't ready for a nearly three-hour meditation on technology addiction and virtual reality. The film lost an estimated $10 million, and Wenders spent years fighting to release his full vision. It finally emerged in 2015, revealing what might be the most prophetic sci-fi film of the decade.

Split Second (1992)

Directed by Tony Maylam and Ian Sharp

Future London is flooded. Serial killer on the loose. Hard-boiled detective with a death wish. Oh, and the killer might be a demon.

Split Second stars Rutger Hauer as Harley Stone, a burnt-out cop hunting a creature that murdered his partner and now seems to be targeting him specifically. It's part Alien, part Seven, filtered through British cynicism and released in a state that suggests the studio gave up halfway through production.

Because they did. Director Tony Maylam (of The Burning fame) was replaced by Ian Sharp during a chaotic shoot plagued with script problems and budget cuts. What survived is a beautiful mess: atmospheric, genuinely creepy in places, and anchored by Hauer doing what he does best—playing damaged men with unexpected depth.

Critics savaged it. The box office ignored it. But cult audiences discovered a film that understood atmosphere matters more than coherence, and Rutger Hauer eating chocolate bars to stay awake for days feels more authentic than most detective clichés.

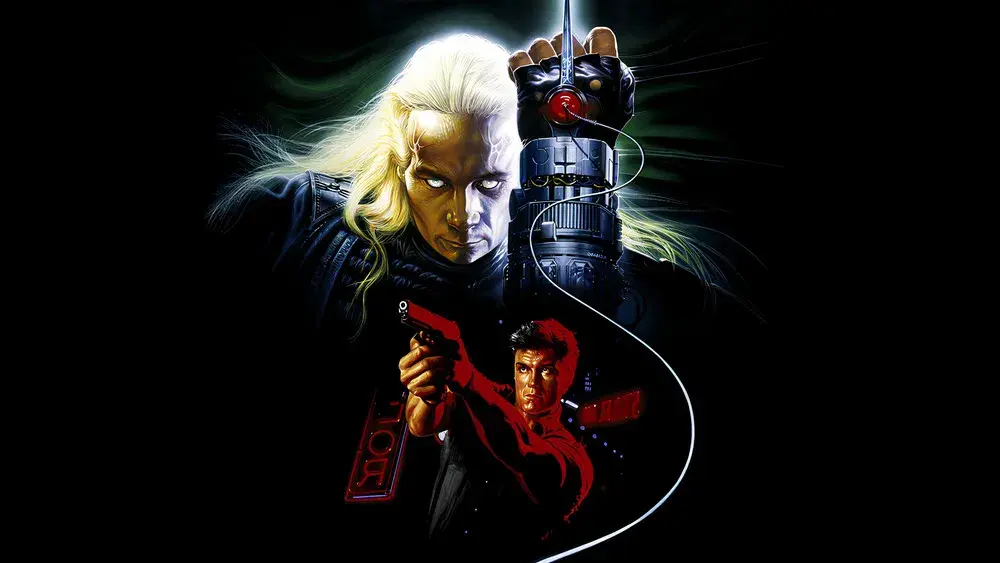

Nemesis (1992)

Directed by Albert Pyun

Albert Pyun made this cyberpunk action film for under $2 million, and somehow it looks better than films with ten times that budget.

Nemesis stars Olivier Gruner as Alex Rain, an LAPD cop in 2027 Los Angeles who discovers he's mostly cyborg parts after a bombing nearly killed him. Now his former employers want him dead, and he's caught between human resistance fighters and an AI conspiracy.

The plot makes little sense if you examine it too closely. Don't. Just enjoy Pyun's incredible eye for industrial locations, brutal action choreography, and a willingness to blow things up in ways that somehow look both cheap and spectacular.

Nemesis spawned four increasingly incoherent sequels, none featuring Gruner. But the original remains a masterclass in low-budget sci-fi filmmaking that understands style and energy can overcome limited resources.

Body Snatchers (1993)

Directed by Abel Ferrara

The third adaptation of Jack Finney's novel might be the most overlooked. Abel Ferrara's military base setting transforms the alien invasion story into something claustrophobic and paranoid.

Teenage Marti (Gabrielle Anwar) arrives at an Alabama Army base with her family, just as the locals start acting strangely. The pods are replacing soldiers, and military conformity becomes the perfect disguise for alien duplication.

Ferrara strips away the 1950s McCarthy-era subtext and Philip Kaufman's 1978 urban paranoia, replacing them with something rawer. His body snatchers don't shriek when they spot humans—they point silently, which is somehow more unnerving. The film's violence is sudden and disturbing, including a bathroom sequence that will make you never look at foam the same way.

Warner Bros. barely released it, dumping Body Snatchers in limited theatres before sending it straight to video in most markets. It earned just $400,000 domestically against a $13 million budget. Ferrara's vision deserved better.

Read Next

From the Vault

Freaked (1993)

Directed by Tom Stern and Alex Winter

This batshit comedy from Bill & Ted writers Tom Stern and Alex Winter (who also stars) is what happens when Fox gives you $12 million and forgets to supervise.

Alex Winter plays Ricky Coogin, a former child star turned corporate spokesperson who ends up at a South American freak show run by the demented Elijah C. Skuggs (Randy Quaid, unhinged even by Randy Quaid standards). Skuggs uses toxic waste to mutate people into attractions. Ricky becomes part of the show.

Freaked features grotesque practical effects, Brooke Shields in a beard, Bobcat Goldthwait as a half-man/half-sock-puppet, and Mr. T as the Bearded Lady. It cost $12 million but earned just $29,296 because Fox panicked and released it in six theatres before dumping it on video.

The studio's loss is cult cinema's gain. Freaked is disgusting, hilarious, and unlike anything else that somehow got studio financing in the early 90s.

Fire in the Sky (1993)

Directed by Robert Lieberman

Based on Travis Walton's alleged 1975 alien abduction in Arizona, Fire in the Sky takes an unusually grounded approach to extraterrestrial contact.

The film spends most of its runtime focused on the aftermath: Walton's logger friends returning to town without him, the suspicion they murdered him, the media circus, and the strain on their community. Director Robert Lieberman doesn't rush to the abduction.

When it finally arrives, though, the sequence is terrifying. Industrial horror aboard a grimy alien ship, with Walton (D.B. Sweeney) strapped to a table while insectoid creatures perform procedures. It's a far cry from Close Encounters' spiritual aliens.

Critics dismissed it as exploitation of questionable UFO claims. Walton's story has been disputed and defended for decades. But Fire in the Sky works as a film regardless of what you believe happened in Arizona, anchored by James Garner's performance as the investigator caught between scepticism and mounting evidence.

Paramount never gave it a proper marketing push, and it faded quickly despite making a small profit. It deserves recognition as one of the few serious abduction films.

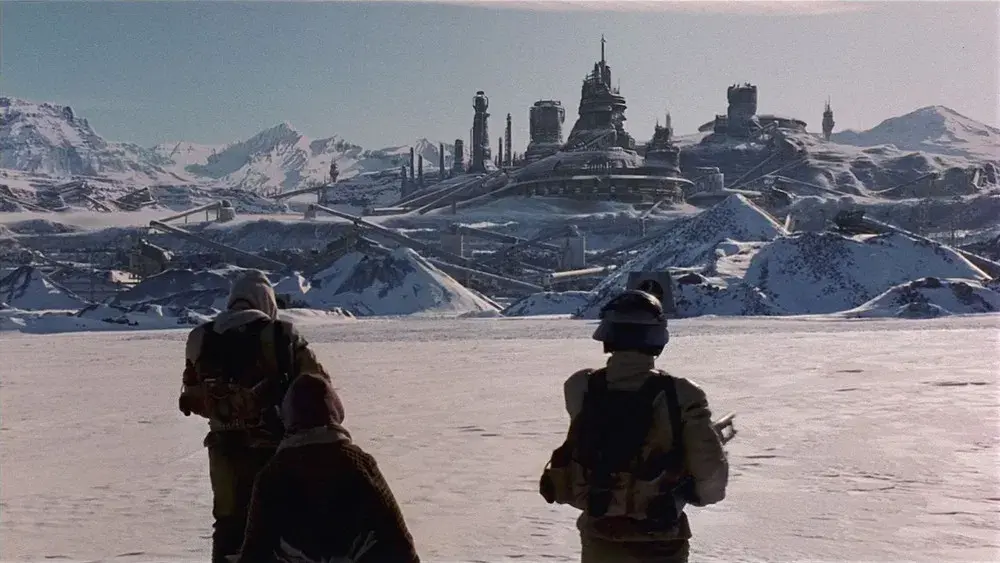

Screamers (1995)

Directed by Christian Duguay

Philip K. Dick adaptations in the 90s were hit-or-miss. Total Recall and Minority Report were hits. Screamers was neither, and that's criminal.

Based on Dick's "Second Variety," Screamers stars Peter Weller as a soldier on a war-torn mining planet where autonomous weapons called "screamers" have evolved beyond their programming. What started as simple burrowing blade machines have learned to disguise themselves. As humans. As children.

Director Christian Duguay creates a genuinely bleak atmosphere on obvious Canadian locations doubling for an alien wasteland. The practical effects are limited but effective. And the film's paranoia—never knowing who's human—captures Dick's themes better than many bigger-budget adaptations.

Sony released it quietly, and it earned just $5.7 million worldwide. But Screamers endures as proof that Dick's ideas work best when filmmakers embrace the pulp terror underneath the philosophical questions.

Strange Days (1995)

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow

Kathryn Bigelow directed this cyberpunk noir about illegal recordings of other people's experiences, released just four years before the millennium it depicts.

Strange Days follows Lenny (Ralph Fiennes), a dealer in "clips"—neural recordings that let users experience someone else's memories and sensations. When a clip surfaces showing a brutal police murder, Lenny is pulled into a conspiracy during Los Angeles' countdown to Y2K.

James Cameron wrote the script with Jay Cocks. The budget swelled to $42 million. The runtime stretched to 145 minutes. Critics praised Bigelow's vision and virtuoso POV sequences showing crimes through victims' eyes.

Audiences stayed away. Strange Days bombed spectacularly, earning just $8 million domestically. Fox took a $30 million loss.

Twenty-eight years later, Strange Days looks prophetic about surveillance culture, police brutality, and technology's role in documenting abuse. The film's depiction of a society addicted to virtual experiences feels less like science fiction every year.

It deserved better than to be remembered as one of 1995's biggest flops. Bigelow's vision was just too early.

Soldier (1998)

Directed by Paul W.S. Anderson

Kurt Russell speaks exactly 104 words in Paul W.S. Anderson's minimalist sci-fi action film. Most are commands like "Sir, yes sir."

Russell plays Sergeant Todd, a soldier raised from birth for warfare and then discarded when a newer generation of genetically engineered warriors makes his kind obsolete. Dumped on a waste planet, Todd finds a peaceful colony and must decide whether he's just a weapon or something more.

Soldier is basically a Western in space—the aging gunfighter defending settlers from outlaws. David Peoples' script (he co-wrote Blade Runner) keeps dialogue minimal because Todd barely knows how to be human. Russell's performance is almost entirely physical, showing a man programmed for violence trying to access buried emotions.

Warner Bros. had no idea how to market a sci-fi film where the star barely speaks, and Soldier tanked with just $14 million against a $60 million budget. Anderson's career took years to recover.

But Russell's commitment elevates what could have been generic material into something genuinely affecting. Todd's journey from weapon to protector works because Russell trusts the audience to read everything in his face and body language.

It's not perfect. But Soldier understands that science fiction works best when it asks what makes us human.

Brainscan (1994)

Directed by John Flynn

Virtual reality horror was everywhere in the mid-90s. The Lawnmower Man, Virtuosity, Strange Days. Most took themselves deadly serious. Brainscan knew exactly what it was: a teenage techno-thriller with a sense of humour about its own absurdity.

Edward Furlong plays Michael, a lonely horror-obsessed teen who orders a new VR game called Brainscan that promises the ultimate experience. The game makes him commit murders. Or does it? Reality and the game blur as a demented character called The Trickster (T. Ryder Smith, clearly having the time of his life) shows up to taunt him.

Director John Flynn—who made Rolling Thunder and The Outfit—brings genuine craft to what could have been disposable teen horror. The film's mid-90s aesthetic is dated in the best way: CRT monitors, chunky VR headsets, grunge sensibilities.

Critics shrugged. Teenagers didn't show up. Brainscan earned just $4 million domestically and vanished into rental obscurity. But it's aged into a cult oddity that understands being a disturbed, isolated teenager better than most films that treated the subject with more seriousness.

No Escape (1994)

Directed by Martin Campbell

Two years before Martin Campbell directed GoldenEye and revitalised the Bond franchise, he made this brutal prison island thriller that nobody saw.

Ray Liotta plays Robbins, a Marine captain convicted of murder and sent to a privatised prison on a remote island. There are no guards. No walls. Just two factions: the savages who murder and rape, led by Marek (Stuart Wilson, gloriously unhinged), and the "Insiders," a civilised community trying to survive.

No Escape is essentially Escape from New York meets Lord of the Flies, elevated by Campbell's kinetic direction and genuine tension. The violence is hard-edged and realistic. Liotta's performance anchors the chaos with exhausted humanity.

Savoy Pictures released it to minimal fanfare. It earned just $15 million against a $20 million budget and was largely forgotten once Campbell became the Bond director. But No Escape deserves recognition as a nasty, effective thriller that takes its pulp premise seriously.

The City of Lost Children (1995)

Directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet and Marc Caro

Before Amélie made Jean-Pierre Jeunet a household name, he and Marc Caro created this surreal steampunk nightmare about a mad scientist who kidnaps children to steal their dreams.

La Cité des Enfants Perdus exists in a world that shouldn't function but somehow does: a rusted dystopia of fog, rust, and Victorian-era technology. Ron Perlman plays One, a carnival strongman searching for his kidnapped little brother. Judith Vittet is Miette, a street-smart orphan who helps him navigate this bizarre landscape.

The film's production design is astonishing. Every frame is packed with grotesque details: clones, a brain in a tank, a cyborg cult, conjoined twins. It's Brazil filtered through French surrealism and German expressionism, shot in burnished golds and greens.

Miramax gave it a limited US release, and American audiences didn't know what to make of a French fantasy film this dark and strange. It earned just $1.7 million domestically. But European audiences embraced Jeunet and Caro's vision, and The City of Lost Children endures as proof that science fiction works best when filmmakers create fully realised worlds that feel alien yet disturbingly familiar.

Related Reading

From the RewindZone archives

The Arrival (1996)

Directed by David Twohy

David Twohy made The Arrival for $25 million and delivered a paranoid alien invasion thriller that out-thought films with triple the budget.

Charlie Sheen plays Zane, a radio astronomer who discovers an extraterrestrial signal. When he's fired and discredited, he investigates on his own, uncovering a conspiracy: aliens are already here, disguised as humans, and they're terraforming Earth through climate change.

This was 1996. Climate change was barely in the public consciousness. The Arrival uses global warming as its invasion method years before it became a political flashpoint, creating tension from scientific concepts rather than action spectacle.

Twohy's direction is economical and smart. The aliens' backwards-bending legs are genuinely unsettling. The film builds paranoia through investigation rather than explosions, trusting audiences to follow scientific detective work.

Orion Pictures gave it a minimal release, and The Arrival earned just $14 million domestically despite decent reviews. It was completely overshadowed by Independence Day that same summer. But Twohy's film is smarter, stranger, and more disturbing than Emmerich's blockbuster spectacle. It treats its audience like adults capable of understanding complex ideas.

Retroactive (1997)

Directed by Louis Morneau

Time loop thrillers became everywhere after Groundhog Day. Most were comedies or high-concept action films. Retroactive is neither—it's a nasty little neo-noir about a woman trapped in a loop with a psychopath.

Kylie Travis plays Karen, a psychiatrist whose car breaks down in the Texas desert. She accepts a ride from Frank (James Belushi, playing violently against type) and his wife. Frank is unstable. Violent. When Karen witnesses him murder his wife, she stumbles into a secret government time machine and gets sent back 20 minutes. She tries to prevent the murder. Makes it worse. Gets sent back again. And again.

Director Louis Morneau understands the time loop's potential for escalating horror rather than comedy. Each iteration gets darker. Frank gets more dangerous. Karen's desperation increases. Belushi is genuinely menacing, playing a man whose volatility makes every scene feel like it could explode into violence.

Orion barely released Retroactive, and it went straight to video in most markets. Critics who saw it dismissed it as derivative. But Retroactive understands that time loops work best when they trap characters with consequences, not quips. It's a tense 90 minutes that deserves rediscovery.

The 1990s gave us incredible science fiction beyond the blockbusters everyone remembers. These ten films took risks, trusted audiences with challenging ideas, and delivered something genuinely different.

They bombed or got buried. Most never found their audience in cinemas. But they're worth discovering now, when streaming makes them accessible and hindsight reveals how forward-thinking they were.

Sometimes the best films are the ones nobody saw.