When Aaron Russo walked out of the screening room in May 1987, the Vestron Pictures executives braced themselves. He'd watched their rough cut. All of it. Now they waited for the verdict from one of Hollywood's most successful producers.

"Burn the negative," Russo said, "and collect the insurance."

That's how much faith Hollywood had in Dirty Dancing.

Every major studio had rejected the script. MGM dumped it during a management change. Forty-three times, producer Linda Gottlieb pitched the story of a girl who falls for her dance instructor at a Catskills resort. Forty-three times, she heard no. Studio executives kept the cassette tapes of songs that Eleanor Bergstein attached to each script—but tossed the screenplay in the bin.

"They were really afraid of girls," Gottlieb later explained. Male studio executives didn't want a woman's story told by women.

The budget was slashed to $5 million. Vestron planned to dump it in theatres for a weekend, then rush it to VHS where they actually knew what they were doing.

Dirty Dancing earned $214.6 million worldwide.

And it killed the company that saved it.

Six People and a Loading Dock

Austin O. Furst Jr. didn't set out to build a film studio. In 1981, HBO tasked him with dismantling Time-Life Films—selling off its theatrical, television, and video divisions. He sold the first two. But nobody wanted the video rights to Time-Life's film library.

So Furst bought them himself.

Working from an old building in Stamford, Connecticut, with just five other employees, he launched Vestron Video. The name came from his daughter's suggestion—Vesta, the Roman goddess of the hearth, plus "tron."

The timing was perfect. VCRs were spreading through American homes. Every new video shop needed a back catalogue, and Vestron had one. Every time a store opened, they'd order not just the latest hits but the entire backlist. Vestron had a built-in market that replenished itself with every new rental shop.

They distributed An American Werewolf in London, Monster Squad, Mad Max. Early offerings included Fort Apache, The Bronx with Paul Newman and The Cannonball Run with Burt Reynolds—films whose theatrical distributors had failed to snap up video rights.

But Furst's masterstroke came with rental.

The major studios were horrified that their films could be rented without consent. They tried contracts, legislation, everything. None of it worked. All it did was alienate video store owners.

Vestron promised complete cooperation. Store owners loved them for it.

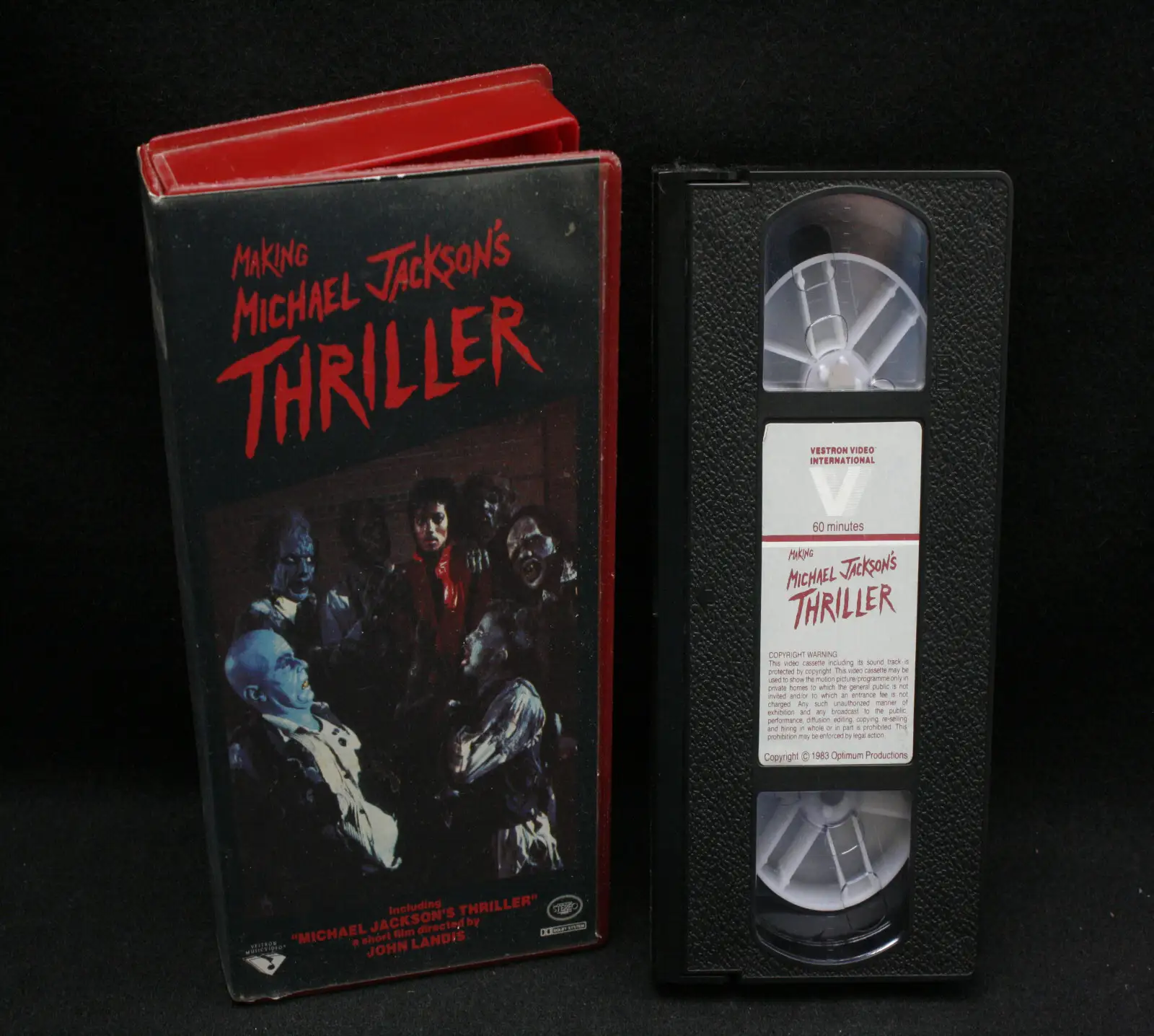

Then came The Making of Michael Jackson's Thriller in 1983. Vestron partnered with Showtime and MTV to produce the hour-long documentary about the music video. Priced at $30, it sold 900,000 units. "We couldn't make them fast enough," Furst recalled.

Furst's model was revolutionary—think like a bookshop, not a movie theatre. Build a diverse catalogue instead of betting everything on individual releases. Travel tapes, educational content, papal visits. Anything that might sell.

By 1985, Vestron went public. At its peak, the company employed over 1,000 people and controlled 10% of the American video market, with distribution in over 30 countries and a manufacturing plant in the Netherlands.

But there was a problem.

Since 1982, Vestron had been distributing video for Orion Pictures, a mini-major studio created by former United Artists executives. Orion's library was a major revenue source—quality films without production risk.

Wall Street knew it couldn't last. Orion would eventually self-distribute. When that contract ended, Vestron would lose its most valuable asset.

To secure the company's future, Furst needed to prove Vestron could produce its own content. The stock sale went through at the end of 1985, with promises to start making films.

This pressure would lead to Vestron Pictures—and ultimately to Dirty Dancing.

Dump Trucks of Desperation

In January 1986, Jon Peisinger made an announcement: Vestron was launching its own production company, Vestron Pictures. No videocassette distributor had ever attempted this before—and none would succeed after. It was a radical experiment, born from Wall Street pressure and Furst's ambitions.

Peisinger's goal? A dozen films a year.

Here's what happened when you were a nobody video company trying to break into Hollywood: the studios sent you their garbage.

"In effect, almost literally, dump trucks with 5,000 scripts or so are dumped in the loading dock in the dumpster," remembered Mitchell Cannold, Vestron's vice president of production.

Every rejected screenplay in Hollywood eventually made its way to Stamford. Scripts that MGM abandoned. Projects that Universal, Warner Bros., and Paramount had passed on. The unwanted, the unfilmable, the unmarketable. Vestron got them all.

Somewhere in that mountain of rejects was Dirty Dancing.

Now for this section, press play and get the full nostalgic effect!

When Cannold finally read it, something clicked. "The life that's depicted in the movie was one I know, one I loved," he later recalled. "I was laughing; I was crying; I got all the jokes; I got all the meaning; I got all the themes of it."

It was the first script that made him feel something.

Bergstein had based the script on her own childhood—summers spent at Catskills resorts in the early 1960s, illicit dancing with working-class instructors, the class tensions and sexual awakening that came with being seventeen and restless. MGM initially showed interest, teaming her with Gottlieb. They finished the script in November 1985.

Then management changed. The new executives put Dirty Dancing in turnaround.

Bergstein and Gottlieb shopped it everywhere. Nobody wanted it. Male studio executives didn't connect with a female coming-of-age story centred on a young woman's sexual awakening and a subplot about abortion. They liked the music cassette attached to the script, though. One after another, execs would pass on the screenplay but pocket the tape.

By the time it reached Vestron, Gottlieb had agreed to slash the budget in half just to get someone—anyone—to bite.

Furst, Cannold, and Ruth Vitale, head of the newly formed Vestron Pictures, all believed in it. They brought in William J. Quigley from the Walter Reade Organisation—a veteran from a three-generation film industry family who knew theatrical distribution inside and out.

They greenlit Dirty Dancing.

Vestron Pictures: Dirty DAncing

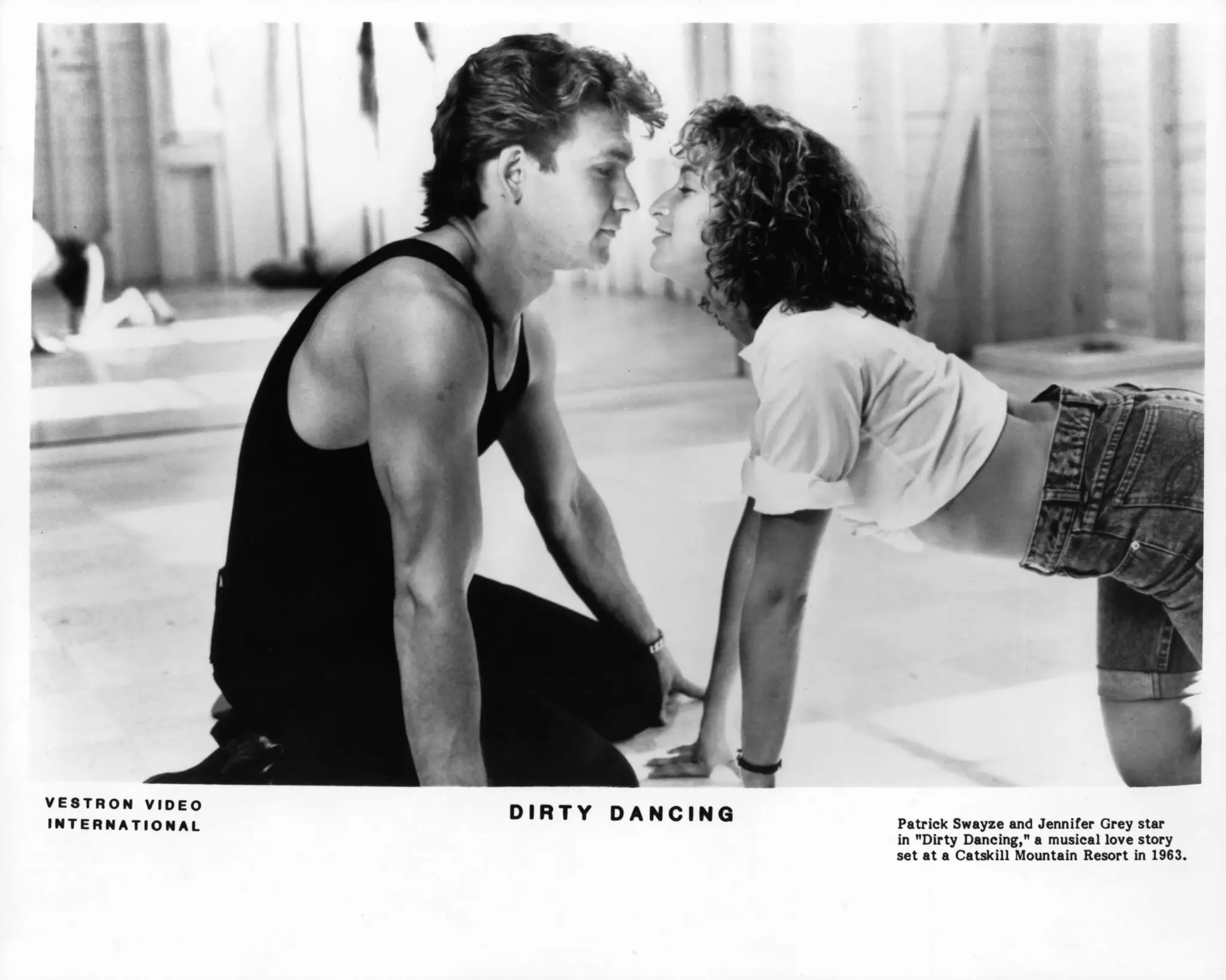

Budget: $5 million. Director: Emile Ardolino, who'd never directed a feature film. Stars: Jennifer Grey and Patrick Swayze, neither of whom were box office draws. Swayze contracted for $200,000. The two had worked together on Red Dawn and often clashed—a tension that followed them to set.

The production was so cheap it bordered on absurd. Shooting began late in the season at Lake Lure, North Carolina, and Mountain Lake, Virginia—standing in for the Catskills because they couldn't afford the actual location. By October, the trees were turning brown. The crew spray-painted dying leaves green. In wide shots, you're watching a summer camp held together by aerosol cans and desperation.

For the famous water-lift scene, Swayze refused a wetsuit despite the freezing October water, insisting it would look more authentic. He sustained an injury from the cold, as well as falling off the log (in the log scene) and aggravating an old knee injury. That's the level of commitment a $5 million budget demanded.

Filming wrapped on 27 October 1986. On time. On budget.

Everyone who watched the rough cut thought it was terrible.

Burn the Negative

Vestron executives knew they had a problem. Test audiences were confused—39% didn't even realise abortion was part of the subplot. The dance sequences felt off. The pacing dragged. Grey's agent watched it and told Bergstein and Gottlieb it would make them a laughingstock.

That's when they brought in Aaron Russo. His advice? Collect the insurance money and move on.

Clearasil had signed on for a cross-promotional campaign targeting teens. When they discovered the abortion storyline, they demanded it be cut. Vestron refused—and lost the sponsor.

What Happened To?

Check out these articles to see what happened to other big stars who faded from the spotlight:

Distributors and exhibitors didn't want it. Vestron planned to release Dirty Dancing in theatres for one weekend in August 1987, then dump it straight to video where they could at least recoup costs through their existing distribution network.

The film limped into nearly a thousand theatres on 21 August 1987. It earned $3.9 million opening weekend.

Then something extraordinary happened. Audiences told their friends. People went back for second viewings. Cinemas that tried to pull it faced protests. By Labour Day, ticket sales had increased. The song (I've Had) The Time of My Life climbed the charts, pushing the film. The film's popularity pushed the song. Back and forth.

"The movie's popularity pushed the song, and then the song's popularity pushed the movie," said Donald Markowitz, one of the songwriters. "It was a double whammy."

By the time Dirty Dancing left theatres four months later, it had grossed $214.6 million worldwide. The soundtrack sold 32 million copies. (I've Had) The Time of My Life won the Oscar, the Golden Globe, and the Grammy. Vestron sold 300,750 video units by February 1988 alone.

The film nobody wanted became a cultural phenomenon.

But here's the devastating truth: Vestron didn't own the music rights.

In the chaotic scramble of independent film financing, Vestron had struck a distribution deal with RCA Records for the soundtrack. When the album became one of the best-selling soundtracks of all time—32 million copies worldwide—the fragmented music rights and distribution arrangements meant Vestron saw only a fraction of those astronomical profits.

The box office was spectacular. But the real goldmine belonged to someone else. Vestron Pictures had saved Dirty Dancing and helped create a cultural juggernaut, only to watch another company collect the biggest payday.

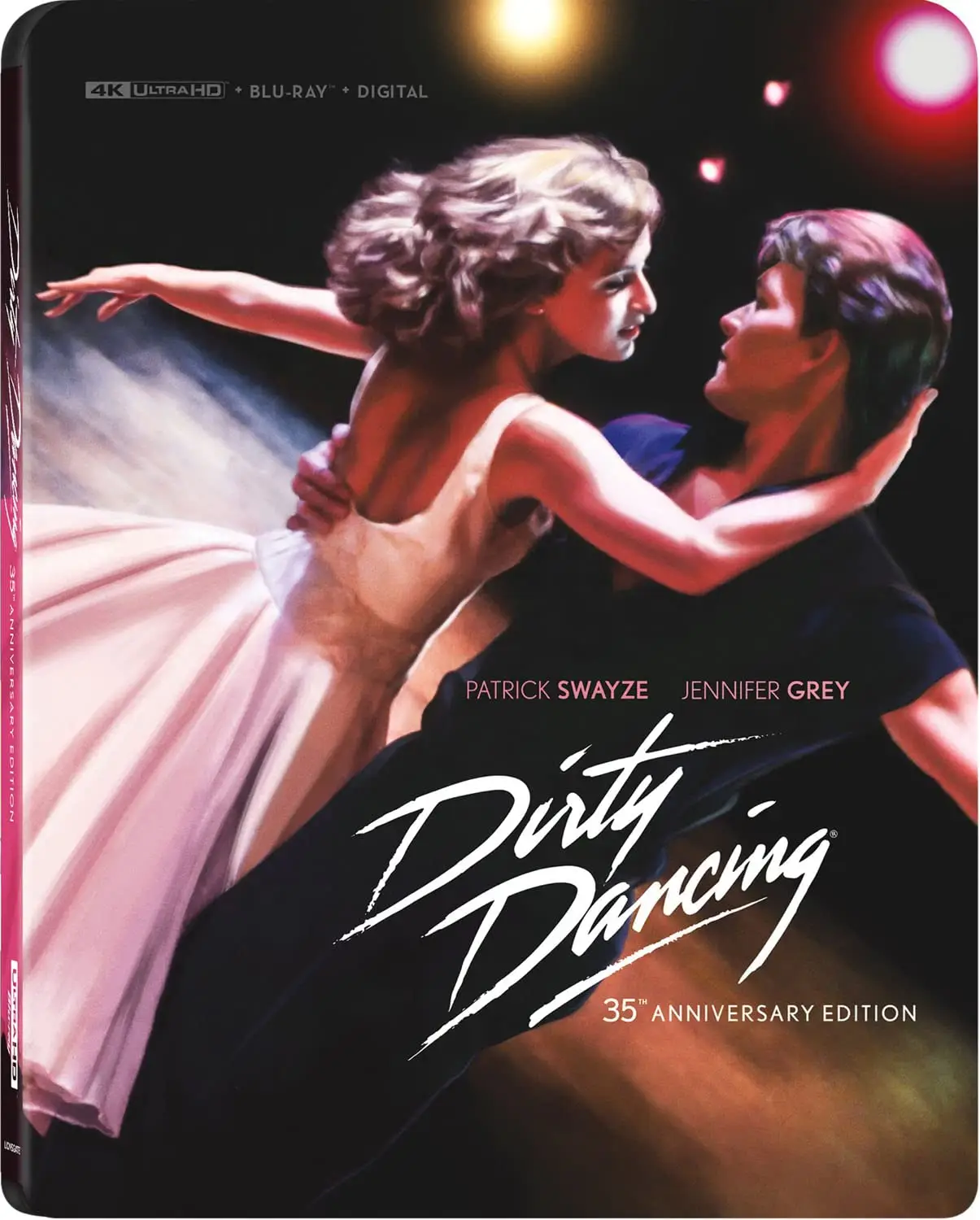

Fancy owning Dirty Dancing in 4K Ultra HD? We earn a small commission from Amazon purchases, which helps keep Rewind Zone running.

We Were on Our Way to the Moon

After Dirty Dancing, Vestron Pictures tried desperately to capture lightning twice. They rushed out Dirty Dancing: Live in Concert in 1988. It sold well but couldn't replicate the phenomenon.

They convinced CBS to greenlight a Dirty Dancing television series starring Patrick Cassidy and Melora Hardin. Despite sharing the film's setting and music, despite choreographer Kenny Ortega directing several episodes, it was cancelled after ten episodes in January 1989.

The failure killed discussions about a prequel—Johnny Castle's life before he met Baby. The project had promise. They never got to make it.

Meanwhile, Vestron continued releasing films. They distributed the international release of The Princess Bride. They made Young Guns, the "Brat Pack Western" that revived the genre. Earth Girls Are Easy with Jim Carrey and Jeff Goldblum. Blue Steel with Jamie Lee Curtis.

By 1988, they had 24 productions slated for release. The company that started in a Stamford office building now had operations in the UK, Japan, Australia, and the Benelux countries.

"We were innovating and making a difference," Furst said. "I thoroughly enjoyed the process. I wish it had gone on forever."

But the market was shifting. And here's the devastating irony: Dirty Dancing's success hadn't given Vestron the financial cushion they desperately needed.

Vestron had taken the risk. They'd greenlit the film everyone rejected. But they'd structured deals that gave away most of the rewards.

Throughout the 1980s, home video audiences would watch almost anything. By 1989, tastes had matured. Audiences wanted A-list titles from major studios. Warner Bros., Universal, Disney—they'd finally figured out the home video business and were now competing directly with Vestron.

Independent producers increased their prices. In 1983, Vestron could buy video rights for a couple hundred thousand. Now it cost millions. Vestron found itself squeezed from both sides—paying more for worse material.

The company had committed to a pipeline of about 20 projects, expecting the market to stay the same. It didn't. Without a clear brand identity, each film had to be sold from scratch.

Then the bank pulled the rug out.

A Hideous Problem with the Bank

In 1989, Vestron lost its $100 million credit line. Security Pacific, the bank Vestron worked with, was actively seeking to sell itself—and succeeded, eventually becoming part of Bank of America. Suddenly, Vestron couldn't finance its production slate.

The company laid off 140 employees, mostly from Vestron Pictures. Then another 250 in early 1990. For the first nine months of 1989 alone, Vestron reported losses of $87.8 million on $169.5 million in sales.

"The whole thing was a beautiful ride up until we had a hideous problem with the bank," Furst admitted.

Theatrical output dwindled to a trickle. Their last few releases limped into cinemas and died. A Gnome Named Gnorm got stuck in distribution hell—shot in 1990, it wouldn't see a US theatrical release until 1993, long after Vestron was gone.

Vestron never got to see either happen.

On 11 January 1991, LIVE Entertainment bought Vestron for $27.3 million—a fraction of what the company had been worth at its peak.

Furst sued Bank of America and walked away with a $100 million settlement.

But his company was gone.

Vestron Pictures' parent company, Vestron Inc., officially filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1992. The extensive library of 3,000+ films was absorbed by LIVE Entertainment, which eventually became Artisan Entertainment, which Lionsgate acquired in 2003.

The Vestron name continued appearing on home video releases until 1993, then vanished.

The Building Still Stands

Today, if you drive past 60 Long Ridge Road in Stamford, Connecticut, you'll find an ordinary office building. When Netflix's documentary crew visited in 2019, they brought Mitchell Cannold and Dori Berinstein back to walk those hallways one more time.

The two had met during the making of Dirty Dancing. They fell in love on that chaotic set where nobody believed the film would work. They've been married ever since.

It's the one love story from Dirty Dancing that actually lasted.

There's no plaque on the building. Nothing to indicate that this small Connecticut company once saved one of Hollywood's most beloved films.

What Vestron Actually Released

From 1986 to 1992, Vestron Pictures released 42 theatrical films. The lineup was surprisingly solid—they had taste, they just couldn't monetise it quickly enough.

They gave the world films that found devoted audiences years after Vestron was gone. Earth Girls Are Easy, Parents, Blue Steel—all became cult favorites or critical darlings.

Vestron Pictures: Parents and Earth Girls Are Easy

The trajectory tells the story: Four films in 1986. Twelve in 1987 after Dirty Dancing hit. Thirteen in 1988 at peak confidence. Eight in 1989 as money dried up. Three in 1990. Then nothing.

But their distribution deal with RCA for the Dirty Dancing soundtrack meant they saw only a fraction of its massive profits. They couldn't afford to release Blue Steel themselves. By 1990, Little Monsters went to United Artists because Vestron had run out of money. And somewhere in that chaos, they lost Pretty Woman—a film that would gross $463.4 million worldwide.

Vestron's rise and fall became so emblematic that business analysts coined a term: "the Vestron Law." The pattern works like this: innovators license content from creators and build a new market. Once the market proves profitable, the original content owners realize they don't need the middleman anymore. They take back their rights. The innovators who proved the concept get squeezed out.

"Home video came right back to the [film] industry," Furst later observed.

The pattern plays out today with YouTube, Facebook, Spotify. The Vestron Law never went away.

In 2016, Lionsgate revived Vestron Video as a boutique Blu-ray label, releasing pristine transfers of Parents and Blood Diner for cult film collectors. It's a fitting tribute for a company that made its name on B-movies and cult classics before accidentally creating a romantic phenomenon.

Every studio in Hollywood had passed on Dirty Dancing. The little video company from Connecticut that nobody had heard of—the one working from an office building in Stamford with a handful of employees and a dream—they were the ones who said yes.

They believed in a script about a girl who falls for her dance instructor. They spray-painted leaves green to make it through production. They watched Aaron Russo tell them to burn the negative. They released it anyway.

Dirty Dancing earned $214.6 million worldwide. The soundtrack sold 32 million copies. The film became a cultural touchstone that endures nearly forty years later.

Vestron Pictures lasted six years.

"We were on our way to the moon," Furst said, looking back. "But it was not meant to be."

The film is forever. The company that saved it exists now only in the memories of the people who worked there, in the Blu-rays that bear its name, and in that ordinary office building in Stamford where two people once fell in love making a movie nobody wanted.

Nobody puts Baby in a corner. But sometimes, the heroes who save Baby get forgotten anyway.