Imagine someone announces a 2025 remake of The Shawshank Redemption. They promise complete faithfulness to Stephen King's novella. Marketing emphasises returning to the source material, honouring King's original vision.

The backlash would be immediate.

Not because audiences love King's novella—most haven't read it. They'd revolt because any deviation from Morgan Freeman's narration, from Thomas Newman's score, from that final beach reunion would feel like sacrilege.

Here's the paradox: a "faithful adaptation" of the source material would be considered an unfaithful betrayal.

Once a film becomes culturally dominant, it replaces the source in the cultural imagination. Darabont's film has become more sacred than King's novella. The original adaptation has closed the door behind itself.

But Frankenstein keeps getting remade. And we keep arguing about whether filmmakers should.

A Note on Reception: When this argument was posted to r/TrueFilm, the response was near-unanimous: quality trumps everything, case-by-case basis, who cares about the source as long as the film is good. Fair position. But it sidesteps the uncomfortable question at the heart of this debate.

The Film Adaptation Test: Where Do You Draw the Line?

by u/TheRewindZone in TrueFilm

The Question That Wouldn't Let Go

Kenneth Branagh's 1994 Mary Shelley's Frankenstein is a disaster. Campy, operatic, often ridiculous. Guillermo del Toro's 2025 version is gorgeous. Technically superior. Prestige cinema at its finest.

I asked which better serves Shelley's novel. Opinion split almost perfectly down the middle. (see Reddit thread below)

Branagh's 1994 Frankenstein vs del Toro's 2025 version - some thoughts on faithfulness to Shelley's novel

by u/TheRewindZone in TrueFilm

My answer was clear: Branagh. Not because his film is better—it isn't. But because it's more faithful to what Shelley actually wrote.

That position triggered an interesting response. The overwhelming consensus was: who cares about faithfulness? Quality matters. If sticking to the novel makes it boring, just read the book.

But that response strawmans the entire debate.

Nobody is arguing for word-for-word transcription. Nobody wants actors reading passages whilst standing still. Of course adaptations require changes for the medium. Novels weren't written for cinema. Internal monologue becomes visual storytelling. Page counts get condensed. Some characters merge. Subplots get trimmed.

Every director brings creative vision. Every screenwriter makes choices. That's not just inevitable—it's necessary. Even the most faithful adaptations transform prose into something cinematic.

But there's a difference between adapting for the medium and fundamentally contradicting core themes.

Branagh kept the Creature horrifying throughout. De Niro's appearance—scarred, wounded, visibly monstrous—doesn't match Shelley's description of flowing black hair and proportionate limbs, but it captures what matters: Victor's instinctive revulsion never fades. The Creature remains an object of horror. The ending offers no redemption, only mutual destruction. Messy, campy, flawed—but faithful to Shelley's nihilistic tragedy.

Del Toro made different choices.

His Creature has advanced healing. Scars fade. Speech evolves from guttural to Shakespearean. Teeth straighten. By film's end, Jacob Elordi has transformed from monstrous to artfully composed. Victor asks forgiveness. They embrace. The Creature walks away with hope for the future.

Beautiful. Moving. Technically superior in every way.

And a complete contradiction of Shelley's vision.

The question isn't "should adaptations change things?" Obviously they must. The question is: when do necessary cinematic changes cross into fundamental thematic betrayal?

When Changes Work

The Shining remains the gold standard. Stephen King openly hated Kubrick's adaptation. King's novel offered redemption—Jack's sacrifice saves his family, the Overlook Hotel burns. Kubrick stripped it away. Jack is corrupted from the start. His madness feels inevitable. The hotel stands eternal.

King's hatred proves the film worked. The adaptation replaced the source.

But King was alive. Could fight back. Did fight back—he even produced his own miniseries to reclaim his vision. The cultural conversation continued because both sides could speak.

Blade Runner transformed Philip K. Dick's internal, philosophical novel into visual noir. Scott made it ambiguous where Dick was explicit. Dick saw it before his death and approved—recognising transformation rather than translation.

Spielberg lightened Jurassic Park considerably. Ian Malcolm dies in Crichton's novel. More characters meet gruesome ends. Spielberg kept the wonder, emphasised adventure, made Malcolm survive. Simplified without dumbing down.

John Carpenter's Christine demonstrates surgical simplification. King's novel features ghost possession—Roland LeBay's spirit corrupts Arnie through the car. Carpenter scrapped the supernatural entirely. His Christine is simply alive, established from frame one. What could have been generic haunted object became twisted love story. The betrayal worked because Carpenter understood the novel's engine: obsession destroying someone from inside. He kept that, lost the rest.

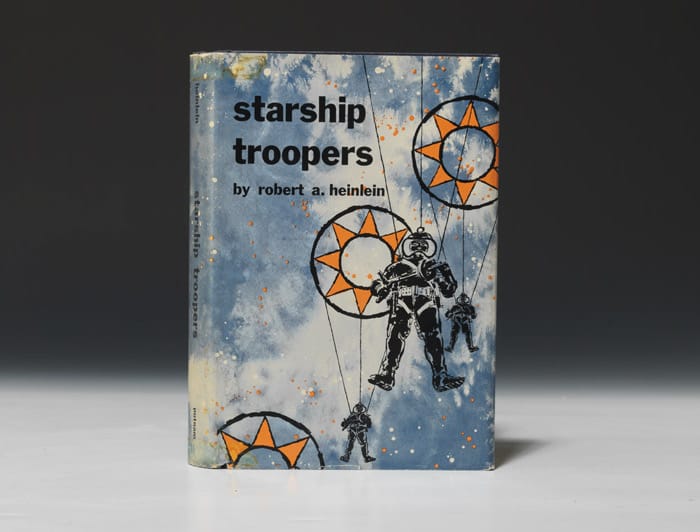

Then there's Starship Troopers. Paul Verhoeven took Robert Heinlein's militaristic novel and made it anti-fascist satire. The source material's ideology needed subversion. Verhoeven kept the structure—space marines fighting bugs—whilst inverting the meaning. The film mocks everything the novel celebrates.

These worked. But they also share something: either the author consented, or the source material itself was problematic enough to justify ideological challenge.

The Question No One Wants to Answer

Mary Shelley died in 1851. She cannot defend her work. Cannot clarify her intentions. Cannot approve or reject adaptations bearing her name.

Frankenstein is public domain. Legally, anyone can adapt it however they want. Add romance. Provide redemption. Turn it into comedy. No estate protects it. No copyright prevents fundamental changes.

So the question isn't about legal rights. It's about something softer, harder to define: cultural stewardship.

Think of canonical literature like historical monuments. You can paint the Sistine Chapel ceiling bright pink. Legally, if you owned it, nothing would stop you. But there's a collective understanding that some cultural heritage deserves preservation because it belongs to everyone now.

When an author's work becomes foundational—taught in universities, embedded in cultural consciousness, referenced for centuries—it transcends individual ownership. The work becomes part of our shared intellectual heritage.

Dead authors cannot defend what they created. We collectively become its stewards.

The uncomfortable question: does that stewardship carry any ethical obligation?

The Hierarchy of Respect

Not all source material sits on the same cultural level.

Die Hard adapted Roderick Thorp's Nothing Lasts Forever. Almost nobody's read it. The original features an older protagonist, his daughter in the building, much darker tone. McTiernan transformed it into wise-cracking action. Nobody complained because nobody knew the source existed.

Maximum freedom granted.

Michael Crichton's novels, King's early horror, Philip K. Dick's science fiction—these were respected within genres but not taught in university literature courses. Filmmakers could elevate them, reshape them, transform them for visual storytelling. The cultural contract allowed significant freedom.

But then there's literary canon. Austen. Fitzgerald. Shakespeare. Shelley.

These aren't just successful books. They're foundational texts. Changing them doesn't feel like transformation. It feels different.

Adrian Lyne's 1997 Lolita demonstrates how to handle canonical literature. Nabokov is untouchable—genuine literary master, prose layered and brilliant. Lyne cast an older actress, adjusted visual tone, simplified some internal monologue. Practical changes for the medium.

But he preserved what was sacred.

The moral complexity remained. Humbert's self-aware monstrousness came through. Jeremy Irons captured the pathetic quality of someone who understands his wrong but still wants it. The film doesn't soften Nabokov's darkness. Dolores' life is ruined. She slides into mediocrity. The tragedy is complete.

Lyne understood Nabokov's darkness was the point. Making Humbert sympathetic or adding redemption would betray everything.

That's the test for canonical literature. Not whether you make practical changes for the medium, but whether you preserve what made the work canonical in the first place.

When directors add redemption where the source offered none, soften tragedy because modern audiences prefer hope, turn nihilism into reconciliation—they're not adapting difficult material. They're making it more palatable.

The question becomes: does canonical literature deserve protection from being made easier to digest? Or is accessibility—making difficult themes more comfortable—a valid artistic choice that keeps classics alive for new generations?

The Truth in Advertising Problem

Here's where the debate gets specific.

Why does 10 Things I Hate About You escape scrutiny whilst del Toro's Frankenstein generates heated debate?

10 Things I Hate About You changes almost everything about The Taming of the Shrew. Modern high school. Teenage characters. Contemporary dialogue. Even the ending—Kat isn't "tamed," she chooses Patrick on her terms.

Nobody complains.

Del Toro keeps period setting, Gothic atmosphere, narrative structure. The DeLacey family sequence is there. The Arctic framing device remains. But it adds redemption, and roughly half the people engaging with this question believe that's betrayal.

The difference isn't in what changed. It's in what was promised.

Signalling Matters

Some adaptations clearly signal "we're doing something different." Others present themselves as faithful. When thematic betrayals follow faithful presentation, it feels like broken promises.

10 Things I Hate About You signals transformation immediately.

No connection to Taming of the Shrew

Different title. Modern setting from frame one. Teen comedy genre. The cultural contract is clear: loose inspiration, not serious adaptation.

Clueless barely mentions Austen. Different title, Valley girl comedy, Beverly Hills setting. Most viewers don't know it's based on Emma.

Apocalypse Now took Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness and moved colonial Africa to Vietnam War. Radically different context. But the title changed. The setting announced transformation. Nobody expected faithful adaptation.

Akira Kurosawa proved this repeatedly. Throne of Blood transplants Macbeth to feudal Japan. The Bad Sleep Well reimagines Hamlet in corporate Tokyo. Ran transforms King Lear into samurai epic. Radical changes—culture, setting, visual language. But the tragedies remain intact. Washizu still falls. The corruption still spreads. Lear's kingdom still collapses.

Now compare adaptations putting the author's name in title: Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, Bram Stoker's Dracula.

When titles promise faithfulness

That signals faithfulness claims. When Shelley's name is right there, audiences expect thematic accuracy.

Del Toro's film is simply titled Frankenstein. Period setting, Gothic atmosphere, prestige drama tone all suggest faithful adaptation. Marketing emphasised source reverence. It looks faithful. Sounds faithful. Presents itself as faithful.

Then offers redemption where Shelley offered none.

This is where the ethical question sharpens: if you're going to fundamentally invert core themes, should you claim the author's authority whilst doing it?

The Passion Test

Here's a deliberately extreme hypothetical—not to offend, but to clarify the principle at stake. I'm not suggesting the Bible and Shelley's literature are on level footing!

Imagine Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ made fundamentally different choices:

Jesus survived crucifixion. Renounces his teachings. Becomes a Roman collaborator. Advocates abandoning Mosaic law. The film ends with him living peacefully in Rome.

Still titled The Passion of the Christ.

The outcry wouldn't just be about quality. Even if technically brilliant, even if emotionally resonant, even if masterfully directed—it would be recognised as cultural desecration. Not because Gibson lacks legal rights (the Gospels are public domain), but because you cannot claim "The Passion of the Christ" whilst inverting what the Passion fundamentally means.

Now scale it down. Not scripture—canonical literature. Not billions of believers—generations of scholars and readers. Not religious desecration—thematic contradiction whilst claiming faithfulness.

The principle remains: if your vision fundamentally contradicts the source's core themes, perhaps the ethical move is changing the title. Signal your transformation. Don't dress your changes in clothes that promise faithfulness.

Frankenstein: A New Vision. Frankenstein Reimagined. Even just The Creature would work. Anything acknowledging you're telling a different story.

But Frankenstein, presented as period-accurate Gothic tragedy, trading on Shelley's cultural authority whilst inverting her nihilistic vision—that creates the ethical tension.

When Ideology Needs Challenge

Not all source material deserves the same respect.

Some texts promote ideology that many consider genuinely harmful. Where's the line between historical documentation and dangerous propaganda? Between preserving difficult history and platforming harmful ideas? That's genuinely complicated—reasonable people disagree.

But here's what isn't complicated: the difference between challenging ideology you find morally dangerous and softening tragedy because it's emotionally difficult.

Verhoeven's Starship Troopers inverted Heinlein's militaristic ideology because Verhoeven believed it needed challenging.

Whether you agree with that choice or not, it's ideological dialogue with the source. Subversion with purpose.

Shelley's nihilistic tragedy isn't promoting harmful ideology. It's not advocating fascism, racism, or violence. It's difficult. Dark. Uncomfortable for contemporary audiences who want redemptive arcs.

Shelley was exploring genuine tragedy—the kind where redemption isn't possible because some mistakes cannot be fixed. That's not morally dangerous. That's emotionally challenging.

There's a clear ethical distinction: challenging what causes harm versus diluting what causes discomfort. One is artistic courage. The other is commercial safety.

You can debate whether certain ideologies deserve subversion. But softening Shelley's nihilism because modern audiences prefer hope isn't ideological challenge—it's making difficult art easier to sell.

The Counter-Argument

The opposing view isn't "change everything" - it's "quality matters more than faithfulness."

Make a good film and audiences won't care how much you deviated. Adaptations keep classics alive by making them accessible to new generations. Cinema isn't literature - the medium demands transformation. Better to have imperfect adaptations that introduce new audiences than perfect preservation that nobody watches.

This sounds reasonable until you apply it to any other cultural heritage.

But the question isn't quality. A beautiful, well-made film can still be intellectually dishonest.

We don't remake museum artifacts in completely different ways from the original. Nobody suggests repainting the Mona Lisa with a bigger smile because modern audiences prefer happiness. We don't chisel David's arms into different positions to update the pose.

Yes, I know! I'm being ridiculous right?

We restore these works, make them accessible, study them in new contexts - but we preserve what made them significant in the first place.

Why should canonical literature operate under different rules?

The argument isn't against adaptation. It's against claiming faithfulness whilst fundamentally contradicting core themes. Adapt Shelley - absolutely. Make it cinematic. Condense for runtime. Merge characters. Adjust dialogue. Transform prose into visual storytelling.

But if you're adding redemption where she wrote tragedy, hope where she wrote nihilism, reconciliation where she wrote mutual destruction - you're not preserving what made the work canonical. You're using her name to tell a different story.

Shakespeare has survived four centuries of interpretation. Classics survive because they're adaptable, not fragile. True. But West Side Story keeps the tragedy. Throne of Blood keeps Macbeth's fall. Romeo + Juliet keeps the deaths. They transform setting, language, cultural context - they don't invert the core meaning.

Nobody's arguing for freezing literature in amber. The argument is simpler: if you're going to fundamentally change what the work means, don't claim the author's authority whilst doing it.

Where Do We Actually Draw the Line?

Synthesising everything reveals uncomfortable questions rather than answers:

When does public domain become public trust? Are we collectively responsible for preserving canonical works, or does artistic freedom override preservation concerns?

If you fundamentally invert a dead author's core themes, do you owe audiences clear signalling that you've done so? Or is period-accurate presentation whilst changing meaning acceptable?

Does the cultural tier of source material matter? Should Shelley receive different treatment than Crichton? If so, who decides which authors are canonical enough to deserve protection?

When ideology is problematic, subversion feels justified. But when themes are just difficult—should difficulty be preserved, or is making classics accessible a valid choice?

Does author consent matter? Living authors can fight back. Dead authors cannot. Does that create greater responsibility, or does death release the work completely?

If filmmakers are going to tell fundamentally different stories—stories about redemption where the source offered none, hope where it offered nihilism—should they have the integrity not to claim the author's authority whilst doing it?

That last question might be the only one with a clear answer.

The Line

The question split opinion 50/50. Which says something interesting: half recognised the difference between adapting for the medium and contradicting core themes. The other half believed quality grants permission to do anything.

It doesn't.

Dead canonical authors cannot defend their work. We collectively become its stewards. Not to prevent adaptation—that would kill literature as effectively as bad adaptations. But to require honesty about what's been changed.

Adapt freely. Transform boldly. Make it cinematic, modern, accessible. Change what needs changing for the medium.

But if you're fundamentally inverting meaning—adding redemption where the source offered none, hope where it offered nihilism, reconciliation where it offered mutual destruction—have the integrity to signal that transformation.

Cultural stewardship isn't about preventing change.

It's about preventing false advertising.